‘Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama’ and its fraught history of birth and rebirth

The Hindu

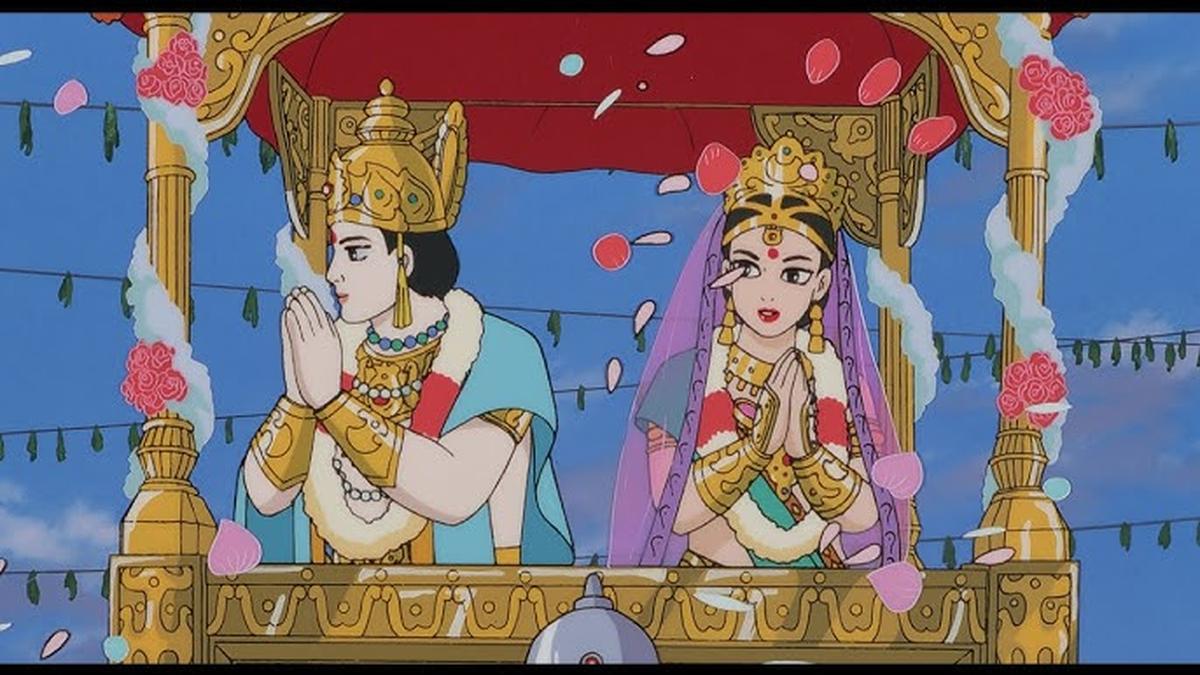

From a serendipitous brush with the architects of the Ayodhya dispute to Studio Ghibli aesthetics repurposed for a modern audience, here’s a deep dive into the tangled legacy of resurrecting this once-controversial anime for Indian screens

Few pop cultural artifacts possess the cross-cultural resonance of Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama.

The epic has long served as the country’s guiding star, endlessly reinterpreted to suit the shifting tides of its storytellers. But for millennials and Gen Xers, whose moral compasses got shaped by Sunday mornings spent glued to Cartoon Network and the last gasps of Doordarshan reruns, Yugo Sako’s animated adaptation occupies an entirely different space, slotted neatly in between Scooby-Doo mysteries, Shaktimaan episodes and other figments of childhood nostalgia.

The Indo-Japanese anime collaboration that first graced Indian screens in the early 1990s has lingered in the collective consciousness, partly for just how pretty it looks and partly for the sheer audacity of its creation. It has since weathered storms of misunderstanding, political controversy, and technological evolution to reemerge three decades later in dazzling 4K glory on Indian screens. For a story that traverses cosmic battles and moral dilemmas, the film’s own journey back to the Indian box office has been no less epic.

You must rewind to the film’s inception to understand why The Legend of Prince Rama still commands reverence. In the early 1980s, Japanese filmmaker Yugo Sako stumbled upon the Ramayana while working on a documentary about archaeological excavations in Uttar Pradesh by former ASI Director General B.B. Lal called The Ramayana Relics.

Enchanted by the breathtaking depth of the story, Sako read ten versions of the Ramayana in Japanese, convinced that only animation could do justice to its divine, mythic scale. Live-action, he argued, could never capture the essence of the titular god without succumbing to the limitations of mere mortal actors.

It’s a strange, almost poetic irony that B.B. Lal’s legacy intertwines so profoundly with The Legend of Prince Ram. Lal’s archaeological work on Ramayana sites captivated Sako and planted the seeds for his animated adaptation. But it was also Lal’s later controversial claims about discovering pillar bases beneath the Babri Masjid that would go on to stoke the fires of the Ayodhya dispute that culminated in the mosque’s destruction in 1992. The once-celebrated archaeologist with a Padma Vibhushan to his name found himself recast in history as both a chronicler of Ramayana’s mythic past and a polarising figure in its very real, modern upheavals. The fact that Sako’s animated vision of the Ramayana should share its origins with the political tensions that unraveled in Ayodhya lingers uncomfortably. It feels like a disconcerting commentary on how mythology can simultaneously get wielded as art and weapon.

But in India, Sako’s ambitions were unsurprisingly still met with skepticism.