The use of archival materials in claims for restitution of idols

The Hindu

Restitution claims for stolen antiquities are supported by pre-theft photographic evidence, as demonstrated by India Pride Project.

Restitution claims are the number one desired result in any effort against the illicit trafficking of antiquities, and pre-theft in situ dated photographic evidence is possibly the most important part of such claims. We demonstrate this with a few examples of how India Pride Project (IPP) helped successfully restitute stolen artefacts and explain how we methodically approach the image crawling, identification, and matching process.

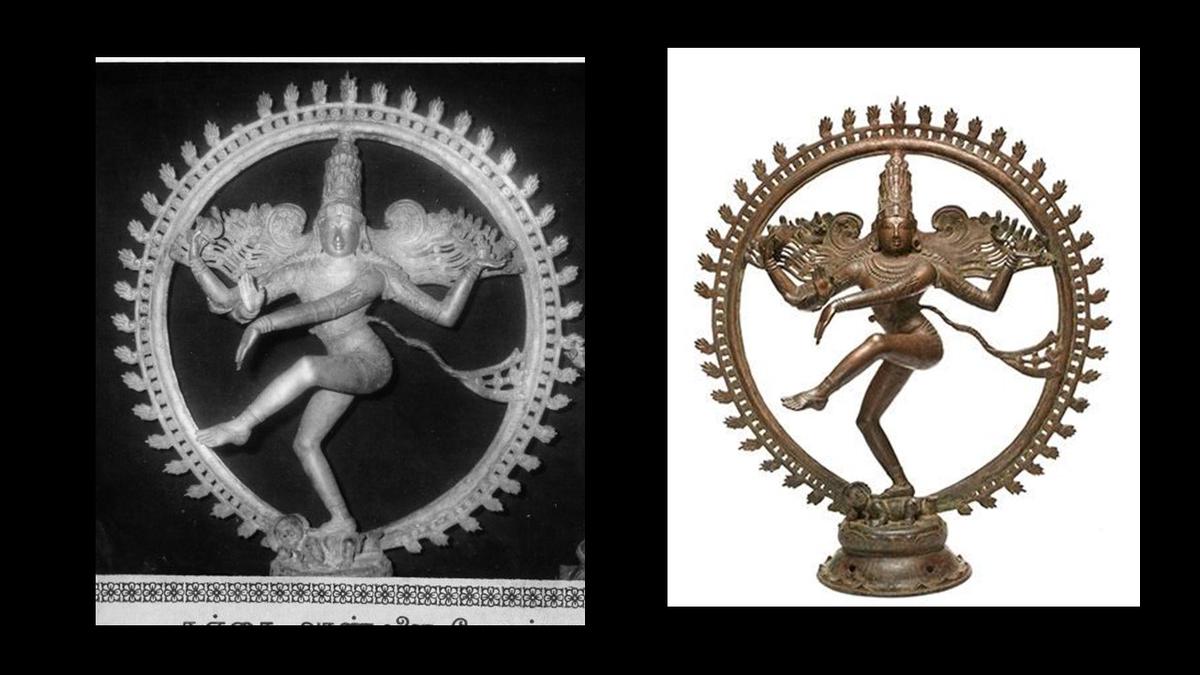

The bronze casting of processional deities in south India reached the pinnacle in the late 9th Century CE under the Chola dynasty. Chola bronzes are considered the high watermark of not just Indian art but also world art. As a result, the art market places a high price tag on them, and they are traded in the millions.

The process of casting these solid bronzes through the lost wax method implies that the final product cannot be scientifically dated; but, since each mould has to be broken to reveal the image, each cast is essentially unique. The bronze casting of ceremonial deities has been in vogue in south India from the 6th Century CE well into the 17th Century CE, covering multiple dynasties with their own unique styling. These bronzes have also been under worship for hundreds of years, and have the resultant wear and tear. In addition, there is a tradition of burying such bronzes for safety in times of invasions, and quite often, they turn up as buried hoards, which are characterised by surface oxidation and sedimentation. A researcher thus must have a deep understanding of iconography, iconometry, coming out of years of studying the different styles, the casting techniques, and a keen eye to spot abnormal wear and tear.

The case of the Ganesha idol of the Sripurantan temple, traced by our team to Toledo Museum, Ohio, U.S., is the first case study we will discuss. The iconography of each deity is carefully described in the cannons: Silpa texts that define the metric or ‘tala’ for every deity, along with its assortment of attributes, gestures and vahanas (vehicles).

The elephant-headed god in this example is cast in slightly lower ‘tala’ — ‘asta (8) talamana’ because Ganesha is supposed to have lost his head in a fight with his father while being a boy and he received an elephant’s head instead. So the weight of the head pushes down on his torso; so he is depicted in 8 ‘tala’, whereas Shiva, Vishnu and other ‘normal’ gods would be cast in 10 ‘tala’. (‘dasa tala’). The 11th Century CE Chola-era icons stayed true to the description of the head of Ganesha.

The first clue in this case came from a volunteer who saw two bronzes in a private gallery in New York with inscriptions in the base. The inscriptions pointed to a village in a particular district in Tamil Nadu. Further investigations revealed a spate of thefts from two adjacent villages.

The French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP) had documented the bronzes in situ in the temple in June 1961!. The IFP had not yet digitised its collection (it has now been digitised), so the custodians actually had a transparency slide which, due to lack of knowledge, was shared. This resulted in a reversed image in the look-out notice. Fortunately, thanks to our understanding of the iconography, wherein Ganesha is to have broken his right tusk to write the epic Ramayana, the source photo was correctly inversed.

Indian Forest Service (IFoS) officer R. Gokul, who was suspended by the State government in connection with a case filed in the Supreme Court seeking permission to denotify 443 acres of HMT forest land, besides writing a letter to the CBI, has reportedly admitted to his mistake and submitted an unconditional apology.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game