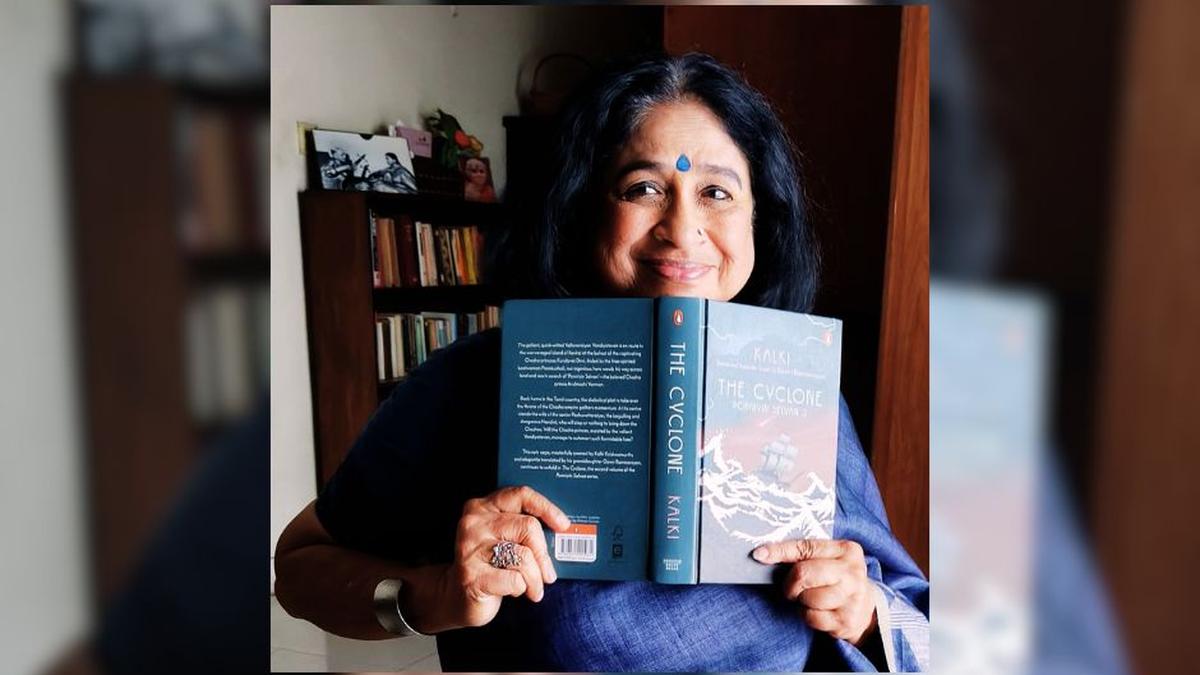

‘The appeal of ‘Ponniyin Selvan’ defies time and logic’ | Interview with translator Gowri Ramnarayan, granddaughter of author Kalki

The Hindu

Kalki's legacy in Tamil literature, explored through his granddaughter Gowri Ramnarayan’s translation of his iconic novel, Ponniyin Selvan.

Kalki Ramaswamy Krishnamurthy, better known by his pen name, Kalki, believed that the test of good writing lay in determining whether it aided the unification of the human community or promoted discord. A pioneering voice in Tamil literature, Kalki has been held in high regard for over a century.

“In him, the activist inflames the writer, the poet coexists with the propagandist, and the creative mind informs the crusading spirit,” writes his granddaughter, the playwright Gowri Ramnarayan, in her four-part translation of his widely popular historical fiction novel, Ponniyin Selvan, which turns 125 this year. The first two books in the series — First Flood and The Cyclone (Ebury Press) — are out this month.

Adapted on screen as well as on stage, Ponniyin Selvan’s popularity has only multiplied over the years. Ramnarayan speaks freely of her relationship with Kalki as a reader, writer, and granddaughter. Edited excerpts:

Kalki died in 1954, after dictating the 26th chapter of his novel Amara Tara from his sickbed. His daughter Anandhi, my mother, then just 23, continued and completed it. Some years later, my uncle Rajendran became the editor of Kalki magazine, followed by his daughters. I’d say that it is they who carried on [Kalki’s] legacy. Though, I believe that only family traditions and values can be passed on. Creativity is your own.

When I became a journalist, my mother said reproachfully, “Your grandfather doted on you, but you write in English!” Later, as a playwright, I was handling a genre that Kalki left untouched. So, though my sensibilities have been shaped by belonging to a family of writers and performing artists, I guess I have never been burdened by any ‘legacy’.

It was all light. No shadows. Though Kalki died when I was only four, I grew up devouring his writings, more non-fiction than fiction. I was inspired by his dauntless integrity, liberal and inclusive outlook, promotion of gender equality, commitment to Gandhian values, ardour for the arts, and most of all, his conviction that freedom was everyone’s birthright. But it was Ponniyin Selvan that made me understand just how books by different writers in every age can make you claim thoughts and feelings from across the world, far beyond your own time, place, experience, and ken. I’d say that the best gift Kalki gave me was the passion for reading. He taught me how imagination is almighty, how powerful language can be.

This is a mystery to me. I am sure it would be to Kalki, too. He thought — and I agree — that Alai Osai (which I have translated as The Sound of Waves) was his best work. And certainly, Sivakamiyin Sapatam (Sivakami’s Vow) is his most realised work in structure and content.