The first judge of the Supreme Court to face impeachment proceedings Premium

The Hindu

Justice V. Ramaswami faced impeachment in 1993, but was saved by abstentions in a dramatic Lok Sabha vote.

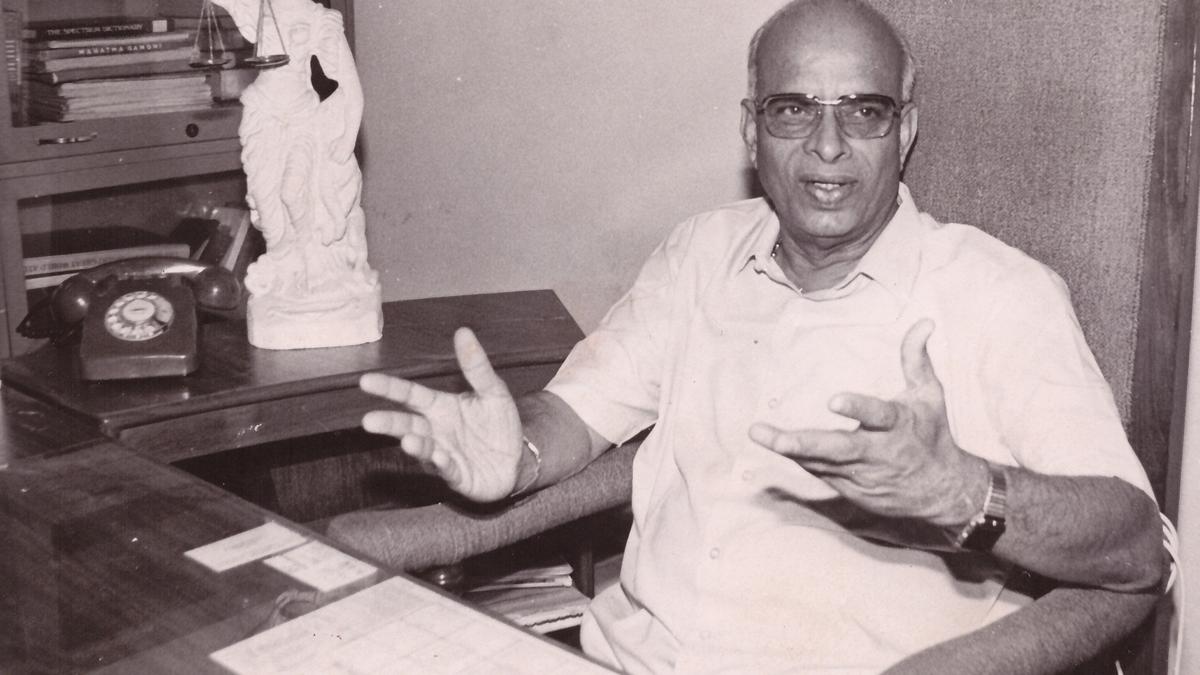

Justice (retired) V. Ramaswami, who died last week in Chennai at the ripe age of 96, was at the centre of a political and legal storm in the early 1990s. He was the first judge against whom impeachment proceedings were initiated. He would have been the first judge of the Supreme Court to be removed from office, had the Lok Sabha adopted the Opposition-sponsored impeachment motion on May 11, 1993.

On the day of voting, 401 members were present. At the time of voting, 196 supported the motion, but 205 abstained, according to a report in The Hindu on May 12, 1993. “Not unexpectedly, the ruling party [the Congress] came to his rescue by abstaining from voting when the Opposition motion of impeachment was put to vote shortly before midnight. The AIADMK and the Muslim League also abstained,” the report added.

According to Article 124 (4) of the Constitution, “a judge of the Supreme Court shall not be removed from his office except by an order of the President passed after an address by each House of Parliament supported by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting has been presented to the President in the same session for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.”

As in the run-up to the impeachment motion, there were dramatic moments during the debate on the motion which went on for 16 hours over two days. Originally, the ruling Congress’s stand was that its members would be given the option of exercising their judgment and vote as they deemed fit after hearing both parties. V.C. Shukla, Union Minister for Parliamentary Affairs and Water Resources in the Narasimha Rao Cabinet, talking of the decision of the executive of the Congress Parliamentary Party [chaired by Rao] on May 9, told reporters that “by not asking the members to vote in a particular manner, we want to uphold the highest tradition”. He gave the rationale behind the decision: it would be improper to pre-judge the matter without hearing the two parties — the mover of the impeachment motion (Somnath Chatterjee, leader of the Communist Party of India-Marxist) and counsel for Justice Ramaswami (Kapil Sibal, who later became Union Minister). Later, the Congress informally conveyed to its members to stay away from the voting. The AIADMK, which announced the separation of ties with the Congress only in March 1993, had, however, gone along with the latter in this matter.

The trouble began for Justice Ramaswami months after he was elevated to the Supreme Court in October 1989 from being the Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court. “The Internal Audit and Accountant-General, scrutinising the expenditure of the High Court, came out with a statement of excess expenditure of a sizeable amount, some of which, in their opinion, was irregular. Petitions against Justice Ramaswami were filed and the Bar strongly agitated against him, insisting that the Chief Justice of India [CJI] should enquire into the matter,” R. Venkataraman, who was then President, wrote in his memoir, My Presidential Years. On July 20, 1990, CJI Sabyasachi Mukherjee, in an unprecedented move, advised his colleague “to desist from discharging judicial functions so long as the investigations in regard to certain audit reports continued and until his name was cleared on this aspect”. He announced his decision in a written statement at the Chief Justice’s packed court hall, immediately after a Constitution Bench that he presided over to hear the Bhopal gas leak disaster settlement review case rose for the day. The CJI had also informed the court that the judge concerned, on July 18, applied for leave for six weeks in the first instance effective July 23.

However, Venkataraman, in his memoir, disapproved of the decision of the CJI as the latter exercised, “however rightly on merits, a power which has not been provided for in the Constitution”. As the impeachment procedure “is tedious and cumbersome”, he had proposed to eminent lawyers and Ministers the idea of ombudsman, which, he said, had found no takers. A day before the Ninth Lok Sabha was dissolved by Venkataraman on March 13, 1991, Speaker Rabi Ray admitted a motion signed by 108 Members of Parliament for impeachment of Justice Ramaswami under Articles 124 (4) and (5) of the Constitution — “dealing with procedure for removal of a judge of a superior court on ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity”. He had constituted a committee, headed by the sitting judge of the Supreme Court, Justice P.B. Sawant, with Justice P. D. Desai, Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court, and Justice O. Chinappa Reddy, former judge of the Supreme Court, as members. A petition was filed in the Supreme Court challenging the validity of Ray’s decision and questioning the continuance of the committee beyond the tenure of the Lok Sabha. However, on October 29, 1991, the court cleared the decks for the probe by the committee into allegations of “financial irregularities” against Justice Ramaswami. A Constitution Bench, by a majority of four (Justices B.C. Ray, M.N. Venkatachaliah, J.S. Verma, and S.C. Agrawal) to one (Justice L.M. Sharma), concluded that under the relevant provisions of the Constitution and the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, the motion admitted by Ray had not lapsed on the dissolution of the Lok Sabha. Justice Sharma held that “the Courts including the Supreme Court do not have any jurisdiction” under the Constitution to go into such a matter in view of the control given to Parliament.

On May 10, 1993, Somnath Chatterjee, who had moved the motion in the Lok Sabha, said it was “not against the entire judiciary but against the behaviour of a judge” that made him unsuitable for the post he occupied. In his more than hour-long speech, Chatterjee said the judge had “made repeated attempts to prevent proper investigation” of the charges and had not cooperated with the three-member committee, lest the truth come out. He faulted the judge for “not utilising deliberately a number of opportunities” given by the committee to present his case. At the beginning of the day’s proceedings, Lok Sabha Speaker V. Shivraj Patil rejected a move by R. Prabhu, who represented the Nilgiris, questioning the locus standi of the present House. Mr. Kapil Sibal, appearing on a specially erected bar, dismissed all the 11 allegations of misuse of public funds against his client as “untrue” and contended that he was “not corrupt”. He defended Justice Ramaswami, who had, according to counsel, accepted his posting from Chennai to Chandigarh when Punjab was a disturbed area and no judge was prepared to go there.