In Delhi, artist Seema Kohli’s show Khula Aasman explores the idea of home

The Hindu

Seema Kohli's multi-media exhibition "Khula Aasman" bridges past and present, exploring nostalgia and family history through art.

Nostalgia need not always be painful. Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) said “One is always at home in one’s past…” This sums up the ongoing multi-media solo exhibition of seasoned artist Seema Kohli “Khula Aasman” in the Capital.

Talking about the project, she says, “I am articulating a tenuous link to a home that my father never returned to. This project is deeply personal, nonetheless, reveals the ephemerality of all belonging.” The varied works connect Kohli with her past, forefathers and ancestral home in Pind Dadan Khan (now in Pakistan’s Jhelum district).

Bridging of the past and present is exhibited in the silver gelatin prints. Using images clicked by her father, KD Kohli, the artist has added colour, ink and pen drawings, some pictures from her archives and recent ones of Pind Dadan Khan by Maria Waseem, providing a fresh perspective. The baraat of her father passing through New Rajendra Nagar’s Shankar Road is framed in the arch of the Shiva temple of Pind Dadan Khan. Urdu poetry and heart motifs on these prints make them engaging. Many of the original pictures are of Seema’s mother Uma who was her father’s muse.

The works portraying the journey of Kohli’s family from Pakistan to India are also fascinating. One shows a train, which was a vital means of transport for refugees during Partition, along with the image of Seema’s studio when it was being constructed, thereby connecting the past with the present. Partition’s barbaric facets are depicted subtly by axes and a shrouded body. Equally riveting is the work juxtaposing Seema’s ancestral house with her New Rajinder Nagar residence wall with images of her grandfather and his friends between the two structures, signifying the passage of time.

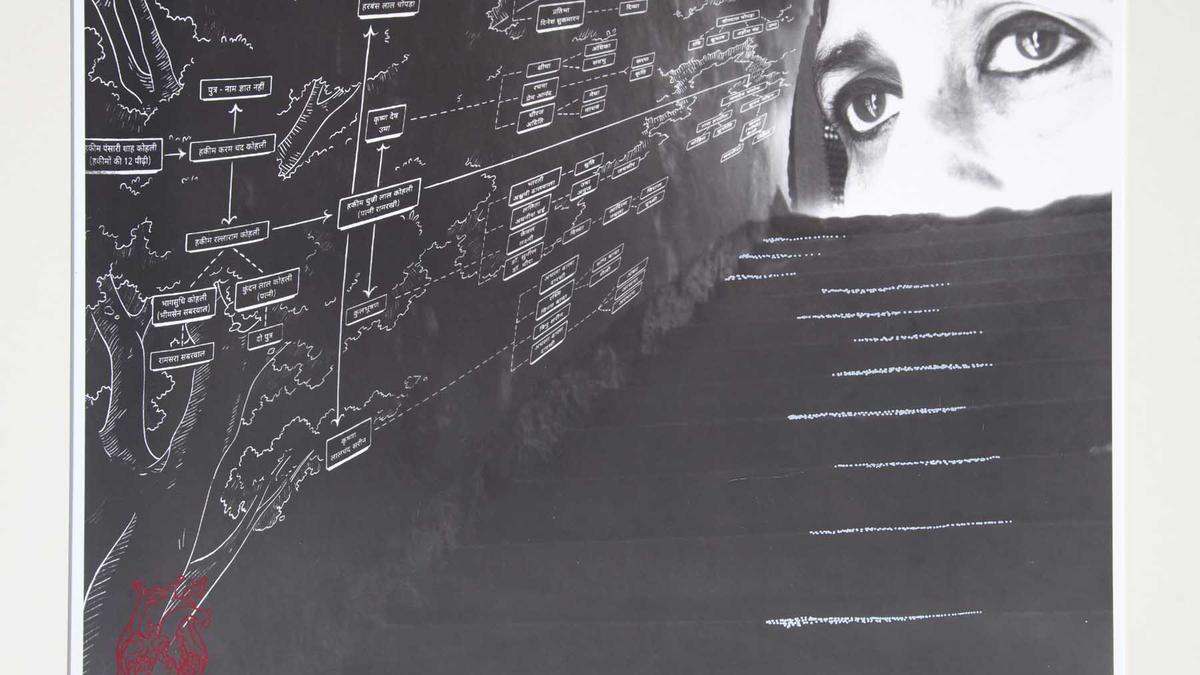

Works highlighting Kohli’s family occupation of hikmat or practice of Unani and Ayurveda medicine are also exhibited. One lists the eight generations of doctors in the family, ending with her grandfather, Hakim Chunni Lal Kohli. Seema’s eyes on the top, looking at the names of her illustrious forefathers, reflect admiration and awe.

The installation reproducing the Appendix from one of her grandfather’s books – Makhzan-i-Hikmat — illustrates the range of treatments offered by Unani and Ayurveda as well as allopathy for varied diseases including cholera, dysentery, and influenza.

A charpoy (bed) covered with a bedsheet showing belladonna herbs and a pill-making machine provide the ambience of a dawakhana. The 12 works outlining the herbs used for preparing medicines, their scientific names, and properties along with glass jars containing murabbas and gulkand, and anatomical drawings of body organs like heart, liver, and lungs, take one to an era when this indigenous medical system was thriving.