Revealing the untold: translated stories of Partition, written by women

The Hindu

Discover the overlooked voices of women in Partition literature through translated works shedding light on their experiences.

Translation works that had long lurked in the shadows, eagerly awaiting exposure, finally received their global recognition in 2022.

That year, Geetanjali Shree’s Ret Samadhi, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell as Tomb of Sand, won the International Booker Prize. Now gaining wide readership, Shree’s 1998 Hindi work Hamara Shahar Us Baras, translated by Rockwell as Our City That Year, is set to be released on August 30, bringing into the limelight the importance of women’s translated books, especially those on Partition literature.

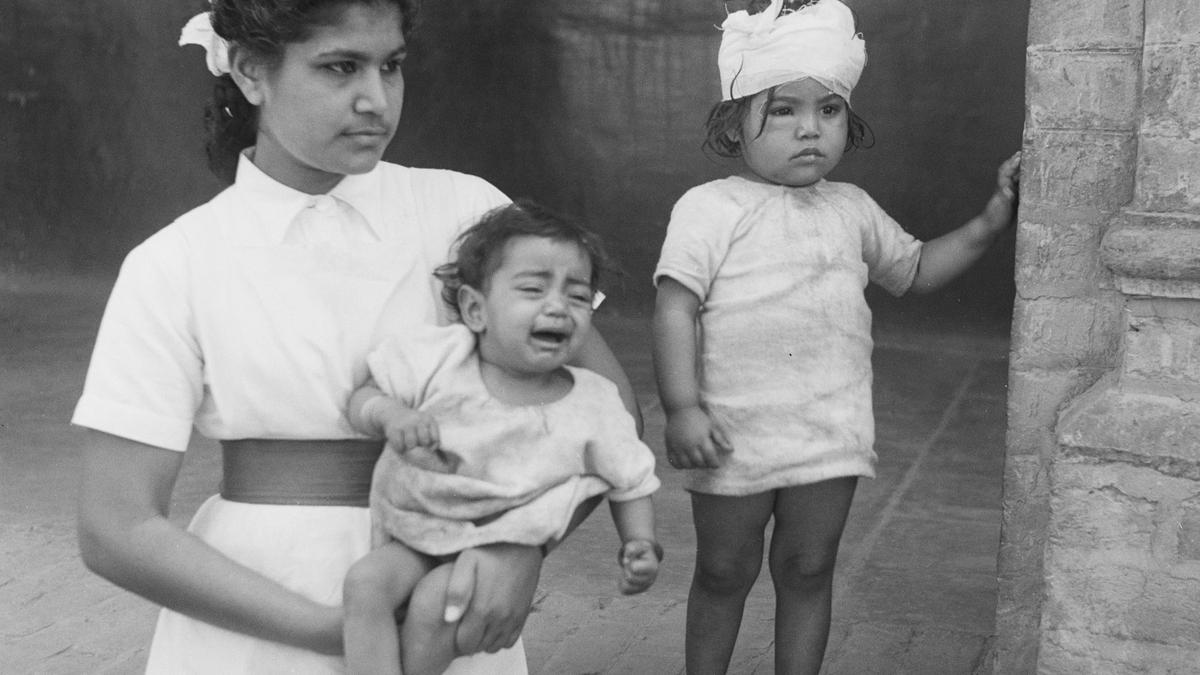

Unlike borders that can be shifted by a stroke of a pen, human identities are deeply rooted; a new homeland cannot replace a lifetime of belonging. The horrors of Partition — 14.5 million people displaced, brutal violence inflicted on women, men, and children, countless women abducted, and myriad other atrocities — have been extensively documented and discussed. However, history has often overlooked the other side of the coin: the experiences of women caught in this crossfire. Confined within their homes against their wishes while men fought wars, their sacrifices and silence have largely gone unnoticed. Yet, a few unwavering women dared to write about the loss of identity, the pangs of nostalgia, the quest for a new sense of self in a shattered world, and the longing to return to their homeland.

Through these translations, we gain insight into the lives of women who, constrained by societal norms and confined spaces, bore the emotional and practical consequences of the Partition.

In Ismat Chughtai’s Jadien (1972), translated as Roots by M. Asaduddin and included in the short story collection Lifting the Veil published in 2001, Chughtai explores the fear of what the future holds and the unwillingness to let go of the past, as it is tied to one’s identity. In this short story, the narrator’s mother refuses to go to the new country while the rest of the family decides to leave. Having spent her entire life in a house where every nook and cranny is filled with memories — of her marriage, bearing children, burying an umbilical cord in the courtyard, and finally witnessing her husband’s last breath — how could she make a new country her identity? If her homeland no longer recognised her, how would the new country, she pondered.

In Khadija Mastur’s Aangan, published in 1962 and translated into English in 2018 by Rockwell as Women’s Courtyard, we witness the claustrophobic lives of women confined within the four walls of their homes.

It discusses how while men step out to fight for justice, it is the women who bear the emotional and financial burdens of their decisions. The protagonist’s mother sacrifices her desire in order to protect her children and maintain family stability despite financial woes. The protagonist, who dreams of pursuing higher education, is instead forced to handle domestic chores against her wishes.