From ‘Black Warrant’ to ‘Visaranai’, how prison dramas explore the human condition

The Hindu

No other setting lends nuanced cinematic takes on the human condition as much as the state-approved confines; as countless films and shows have reflected on, most prisons seem far removed from their rehabilitative purpose, now existing as a mere symbol of apathy and a reminder of human despicability

In August 1971, a psychology professor at Stanford University conducted a study in which college students were offered money in exchange for participating in a two-week prison simulation experiment. Philip Zimbardo wished to understand what such an environment would do to their psyche. Through coin-flips, the participants were segregated into ‘prisoners’ and ‘guards’. In just 24 hours into the experiment, the crucible gave in, with prisoners rebelling against the guards, and the latter resorting to psychological abuse to show prisoners their place. The experiment reached unspeakable heights and was terminated on the sixth day, with the intervention of psychologist Christina Maslach.

In 2015, Kyle Patrick Alvarez made a cinematic retelling of the experiment, called The Stanford Prison Experiment, which incisively took viewers through the experiment; while every progressing situation reveals intriguing psychological results of life in prison, the epilogue is startling, where the participants spell out their experience. Several concurred that putting on a uniform of authority automatically brings out their worst, apathetic selves. From the beginning, we see Michael Angarano’s prison guard character, the despicable John Wayne, ‘enact’ how he believes guards should be. When confronted, he expresses his disbelief in how his abusive authoritarian ship wasn’t questioned enough.

Much of this echoes Tamil filmmaker Vetri Maaran’s belief that the pyramid of power is such that it cannot function with empathy. As the high recidivism rates point toward, most prisons seem far removed from their rehabilitative purpose, now existing as a mere symbol of apathy, a reminder of human despicability.

As several films and shows have shed light on, the prospect of jailing someone is currency by itself, used for political and personal reasons. Filmmakers have captivatingly explored the prison system, attempting to unearth hushed, perverse secrets of our civilised world. Though a sanitised retelling of real events, Netflix’s Black Warrant explored the psychological nuances of life in prison and the politics that make the governing system anything but rehabilitative. When we first meet the infamous Bikini Killer, Charles Sobhraj (Sidhant Gupta), in the series, the pull his presence has on the guards of Tihar seems heroic; but when you see our honest hero (Zahan Kapoor, as Sunil Kumar Gupta) repeatedly ask favours from Sobhraj, the curtain drops. You also see the system for what it is when Sunil’s attempts towards rehabilitation are hindered by his superiors. Like in a particular episode in which criminals Billa and Ranga are hanged, many scenes question our biases.

Several cinematic titles have taken swings at our moral contradictions. Reduced to their primal selves, humans perversely wish to feel liberated from their own social structures and step out of line, if they could face no consequences. They even self-condition their moral compass to live without guilt. They would know better if they watched Ric Roman Waugh’s 2008 drama Felon, which spectacularly shows how a man — imprisoned for accidentally killing an intruder — is brutalised by a debauched institution and forced to abide by gang rules to survive.

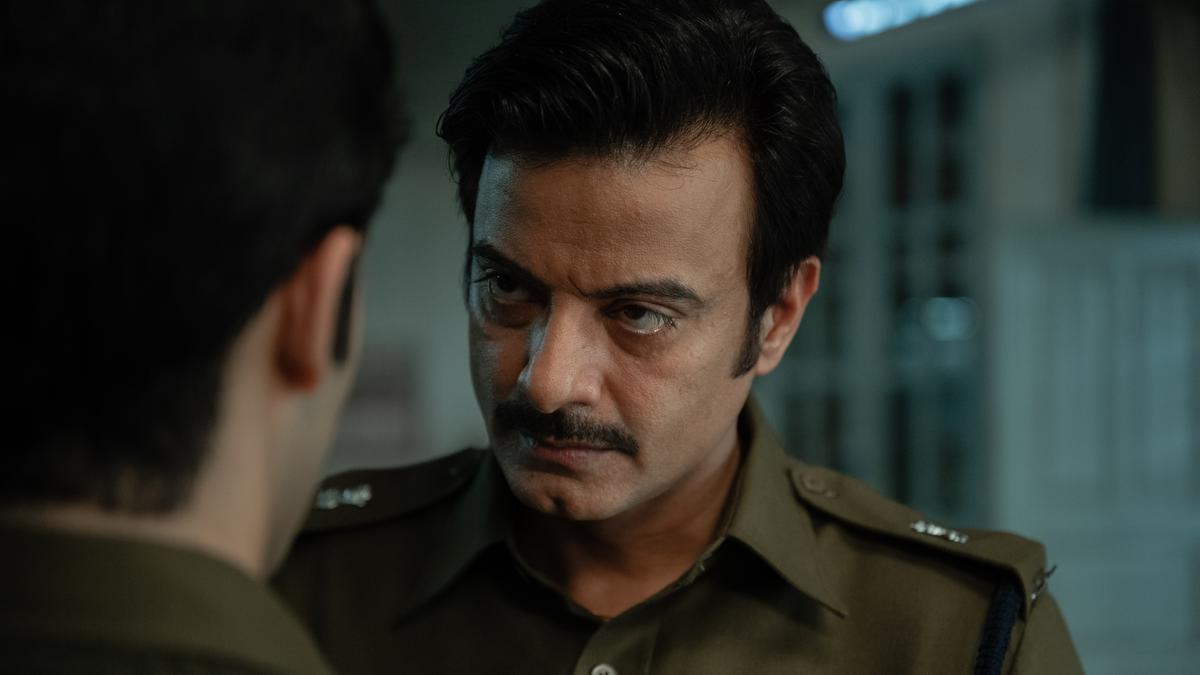

The character of Lieutenant Bill Jackson in Felon embodies a corrupt cog in the prison wheel, a superior who has succumbed to the pressure of prison life. Watching Jackson break down in a parking lot echoes Samuthirakani’s character in Vetri Maaran’s Visaranai, which remains the most gut-wrenching depiction of the filth running deep in our prison system. Post the release of the film, reports cited testimonies of viewers experiencing fear for men in khaki; the many news reports of fake encounters in southern India have only added to the image that Visaranai and successive Tamil films like Jai Bhim and Viduthalai have painted of our police.

In a confine, the only colleagues you have are your prison mates. They could be your friend or enemy, but most importantly, they are the only resemblance of any human relationship you have during your time in jail. They can be your voice of consciousness — like Balaji Sakthivel’s Bashir in Sorgavaasal, a cook who helps RJ Balaji’s Parthiban find purpose — or prove to be ladders to the higher levels of prison hierarchy — like Selvaraghavan’s Siga in the same film. Many Hollywood films have shown how normalised sexual abuse among inmates is in prisons, like 2000’s Animal Factory. In the Steve Buscemi film, when Willem Dafoe’s Earl Copen helps 21-year-old Ron Decker (Edward Furlong), the latter seems hesitant, wondering if all this kindness is a manipulation tactic. Copen, however, proves to be an angel; he educates Ron on the quagmire that is life in prison.

‘The Pride of Bharat: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’: Makers unveil new poster of Rishab Shetty’s film

Upcoming biopic on Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj starring Rishab Shetty, and music composed by Pritam, is set to release in 2027