Artist KGS and his idea of India

The Hindu

In K.G. Subramanyan’s birth centenary year, an exhibition of his drawings from three cities portrays what it means to be an Indian in contemporary society

The celebrated artist, teacher and public intellectual Kalpathi Ganpathi Subramanyan (KGS) was born in Kerala a hundred years ago. At a deeper level, his journey from Palghat to Vadodara, via Chennai, Santiniketan, Baroda and again, Santiniketan, exemplifies the best of the idea of India. From the 1997 book by academic Sunil Khilnani to the erudite dialogue between historian Romila Thapar and theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, we have a framework to understand the contours of the idea of India. While these scholars articulate it in words, the visual language of KGS provides a graphic and pictorial reading of a nation that went through the excesses of both colonial and post-colonial regimes.

The probing question that emerges from the world of Khilnani, Thapar, Spivak and KGS is: what does it mean to be an Indian in contemporary society? I try to answer this through the aesthetic and political journey of KGS, drawing from my personal interaction with the artist and from his prodigious art, writings and lectures over the decades. I am associated with the exhibition called Tale of Three Cities. These are select drawings he did in Beijing, Oxford and New York, and will be displayed at Chennai’s DakshinaChitra Museum from September 7 to December 1.

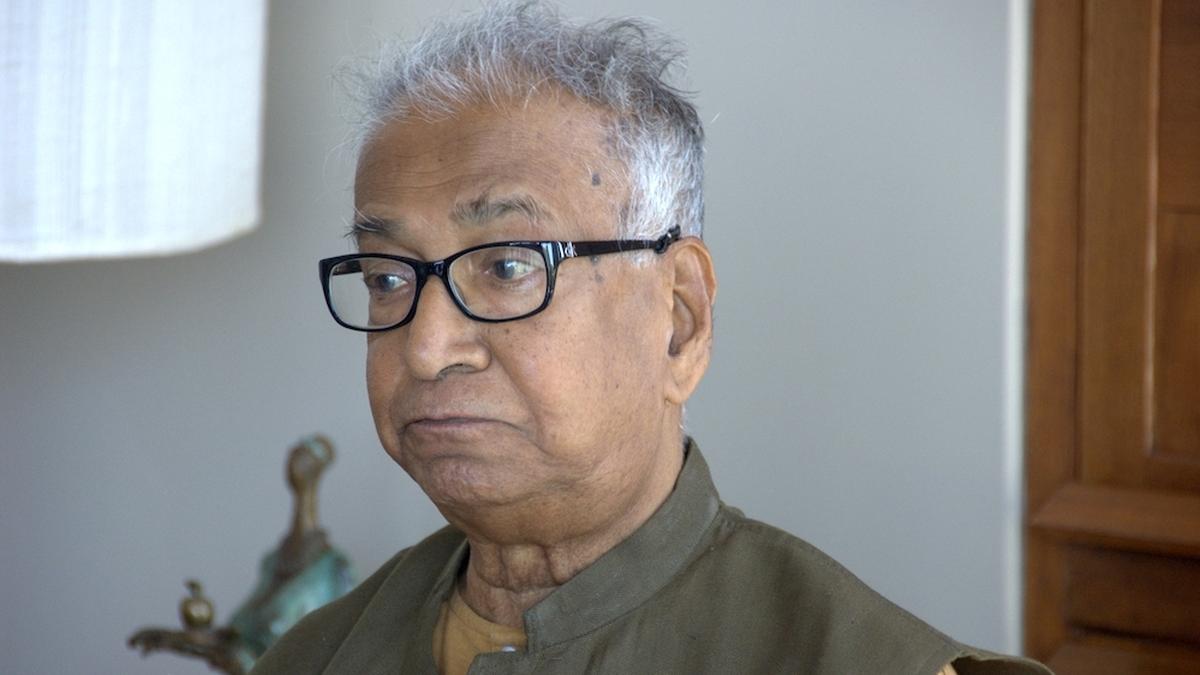

KGS was fondly called ‘Manida’ by his friends and students, and my last interaction with him was in 2012 when he had two shows in Chennai: one at the Lalit Kala Academy and another at Focus Gallery. He visited Cholamandal Artists Village, where I live, and the DakshinaChitra Museum, and interacted with both artists and the general public. A fine raconteur, he spoke about his travels across the country from the colonial times to the present.

The foremost quality of his work is his amazing fluidity. This comes from the fact that he was a Tamil hailing from the Palghat region of Kerala. For Tamils, it is Malayali region, and for Malayalis, it is Tamil region. He was born when the freedom struggle was gaining momentum. History documents the refuge provided by Pondicherry, which was under French control, to Aurobindo Ghose and Subramania Bharati. Mahe provided KGS a similar escape from English colonialism. Mahe today remains a part of the Union Territory of Puducherry, but is situated well within the Malabar region of Kerala.

He lived in Mahe until he was 17 and then moved to Chennai. At the beginning of his wonderful journey of curiosity, beauty, belonging and independence, he took a major decision that remained his hallmark throughout his artistic existence: he signed his works as ‘Mani’ in Tamil.

Most biographical references record the fact that KGS did economics at Presidency College in Chennai. His involvement in the freedom struggle led to his incarceration and he was debarred from government colleges. His interactions with D.P. Roy Choudhury, K.C.S. Paniker and S. Dhanapal gave him the idea of joining Santiniketan, which was outside colonial administration. In 1944, he joined Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan, as a student and graduated in 1948, a year after Independence. His palimpsest of techniques, approach to art and art education draw from the benevolent mentorship of Benode Behari Mukherjee, Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij. Eminent artist Gulammohammed Sheikh, art historian R. Siva Kumar, and founder of The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Naveen Kishore, have documented the multiple streams that have contributed to the artistic universe of KGS and his sphere of influence on modern Indian canvases, murals and drawings.

At Santiniketan, KGS witnessed the assimilatory and accommodative power of art when his teacher Nandalal Bose was invited to visually craft the Indian Constitution. Chennai-based artist K.M. Adimoolam once observed that the Constitution was the first canvas of the modern Indian masters. KGS’ strong idea of what is right and what is wrong, his profound empathy and respect for human dignity, and his abhorrence of all forms of humiliation came from, it seems, watching the crafting of the Constitution by Bose and his team. His illustrated works for children exemplify his unwavering commitment to the founding principles of the republic. I have the privilege of translating one such work for the Tamil audience: The Tale of the Talking Face, set to be released next year.