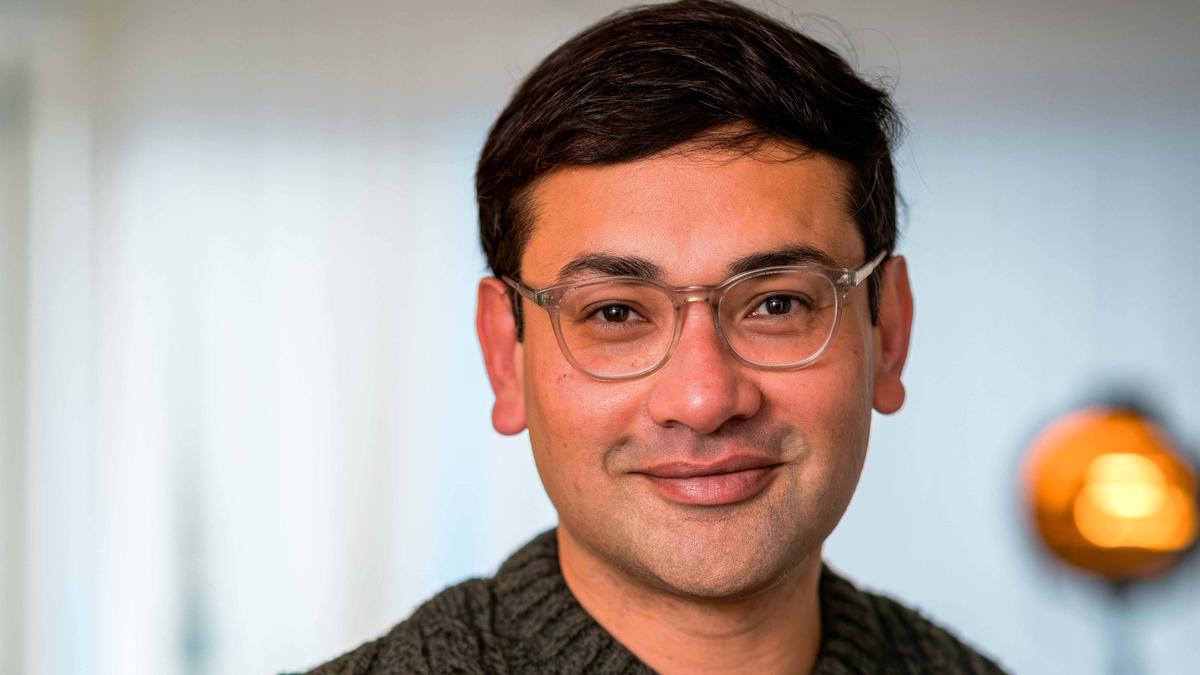

“I’m from a queer generation that couldn’t wait to grow up”: Santanu Bhattacharya, author of Deviants

The Hindu

London-based author Santanu Bhattacharya discusses his novel "Deviants" set in Bengaluru and Kolkata, exploring sexuality and identity across generations.

In an Indiranagar coffee-shop blasting Dua Lipa hits, even before our double-shots of espresso arrive, the 43-year-old London-based author Santanu Bhattacharya quickly tells us that he has a fond history with Bengaluru. “Coming to this city feels a bit like a homecoming, each time,” he says.

He admits he’s changed along with this crazy city but “it still has a very strong place” in his personal history as well as his family’s stories. “It’s our happy decade before the nasty surprises of life hit us.” On moving to Kolkata, he remembers having to “very quickly reconfigure himself” to “an old, big, brash city” which was quite the departure from the “softness, kindness and inclusivity” of Bengaluru back then.

It’s perhaps for this reason, the ‘garden city’ finds itself sweetly slipped into the pages of Bhattacharya’s new novel Deviants (published by Tranquebar), which invites us into the lives of three gay men in the same family. The central character, Vivaan, a 17-year-old, lives in Bengaluru. He’s the one literally telling his story through voice notes on his smartphone. Then, there’s his mother’s brother, Mambro, who grew up in the mid-90s; and finally, Sukumar, the great-uncle, or Mambro’s uncle, who is studying commerce and falling in love with a sculptor in Kolkata of the 70s.

Shifting between these two cities — Bengaluru and Kolkata, explicitly unnamed but honoured in the novel — mirrors Bhattacharya’s own trajectory. For him, through the process of writing fiction, “the lines start blurring so quickly” that it allows for the “taking of liberties” to tell a story that can’t “lay a claim to any truth” either.

While he sees the merit in “reading books around a particular theme, period or place” to try and reflect a similar quality of a time, for Deviants, “the idea itself was building inside” of him for a long time. And, he always knew he wanted to employ three different voices to chronicle the negotiations with sexuality and identity over different generations.

For Bhattacharya, it was important that the characters themselves guide the storytelling and the world-building. And it is this very environment the reader steps into. It isn’t the result of “the author sitting in 2025 and using Google or doing a bunch of reading in the library to create the life or knowledge of the characters”. Bhattacharya says he had to stay in their lane without bringing his “own knowledge and wisdom” to them.

For example, in arriving at Vivaan’s voice — “a mix of sass and vulnerability” — he found inspiration and took courage from the adolescent protagonist’s tone in Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead (2022). Channelling Vivaan in his own words, through voice notes, was always part of the novel’s initial idea because, “I wanted to hear directly from this character,” says Bhattacharya.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game