Supreme Court ruling on socialism, secularism

The Hindu

Supreme Court ruling on socialism, secularism

The story so far:

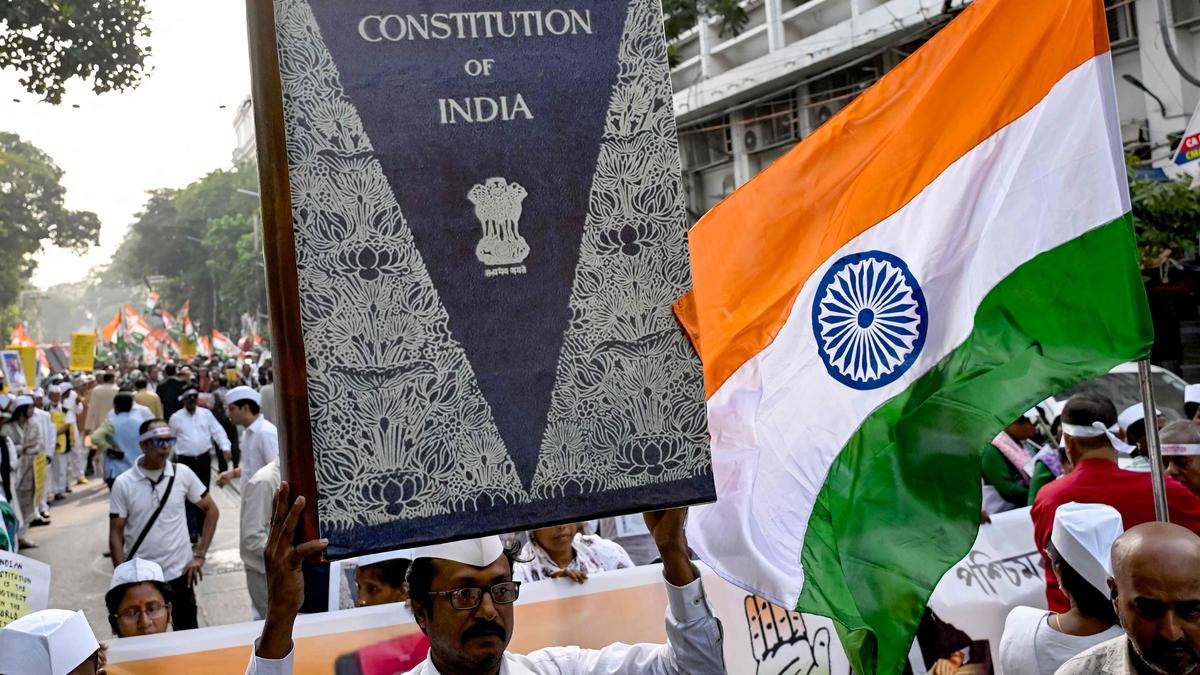

A Division Bench of the Supreme Court led by the Chief Justice of India dismissed pleas challenging the inclusion of the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ in the Preamble to our Constitution.

The original Preamble adopted on November 26, 1949, declared India a sovereign, democratic, republic. Our Constituent Assembly consciously avoided the word ‘socialist’ as they felt that declaring the economic ideal of a country in its Constitution’s preamble was not appropriate. People should decide what suits them according to time and age.

Likewise, Indian secularism is different from western secularism. In the latter, the state and religion are strictly separated and the government does not interfere in religious affairs. However, in India, the state enjoys the power to regulate the economic, financial, political and secular aspects associated with religious practice. It can also provide for social welfare and reform in religious practices. Further, various provisions of the Constitution that include right to practise any religion, non-discrimination on the basis of religion in any affairs of the state embodied the ‘secular’ values of our Constitution. Hence, in the Constituent Assembly, the amendment to introduce the word ‘secular’ in the Preamble was not accepted.

In Berubari case (1960), the Supreme Court opined that the Preamble is not a part of the Constitution and thus not a source of any substantive power. Subsequently, in Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), the Supreme Court reversed its earlier opinion and said that the Preamble is part of the Constitution and that it should be read and interpreted in the light of the vision envisioned in the Preamble. It also held that the Preamble is subject to the amending power of Parliament as any other provision of the Constitution. The 42nd Constitutional Amendment in 1976 inserted the words ‘Socialist’, ‘Secular’ and ‘Integrity’ in the Preamble.

The current case was filed by former Rajya Sabha MP Subramanian Swamy, advocate Ashwini Upadhyay and others. Mr. Upadhyay and others had opposed the insertion of the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ in the Preamble. They argued that these were included during the Emergency and forced the people to follow specific ideologies. They felt that since the date of adoption by the Constituent Assembly was mentioned in the Preamble, no additional words can be inserted later by Parliament. Mr. Swamy was of the view that subsequent amendments to the Constitution including the 44th Amendment in 1978 during Janata Party rule after emergency had supported and retained these two words. Nevertheless, he was of the view that these words should appear in a separate paragraph below the original Preamble.

The court dismissed the pleas and held that ‘socialism’ and ‘secularism’ are integral to the basic structure of the Constitution. It observed that the Constitution is a ‘living document’ subject to the amendment power of Parliament. This amending power extends to the Preamble as well and the date of adoption mentioned in it does not restrict such power. The court opined that ‘socialism’ in the Indian context primarily means a welfare state that provides equality of opportunity and does not prevent the private sector from thriving. Similarly, over time India has developed its own interpretation of ‘secularism’. The state neither supports any religion nor penalises the profession and practice of any faith. In essence, the concept of secularism represents one of the facets of right to equality.