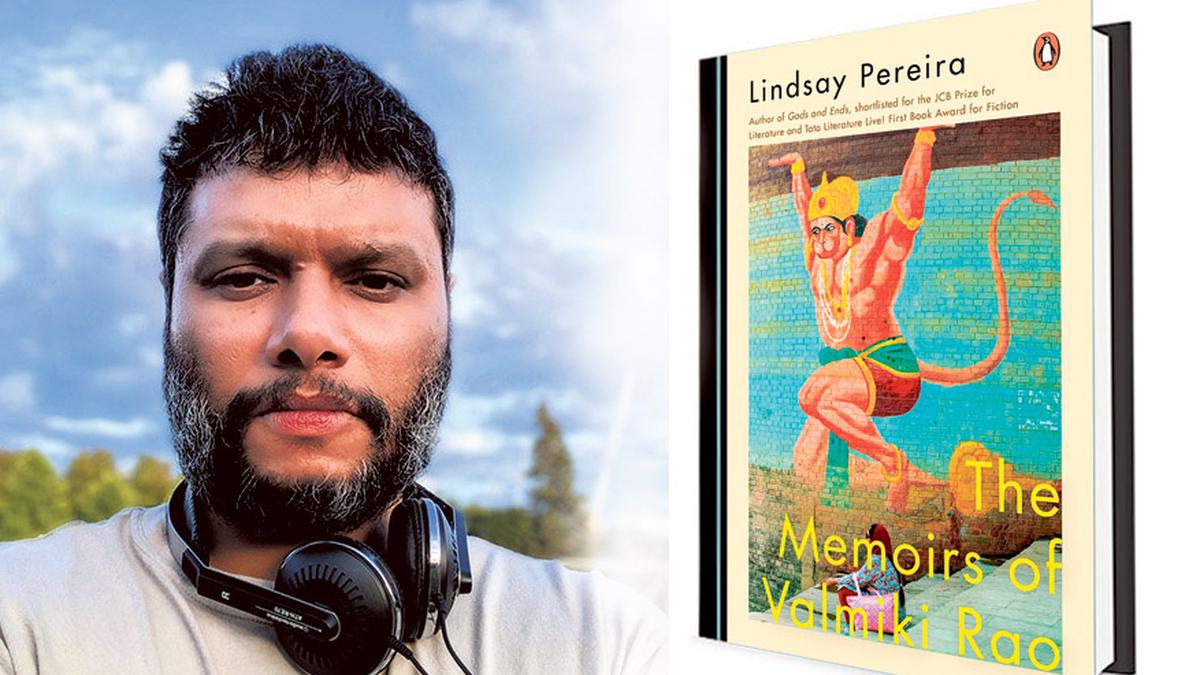

Interview | Mumbai journalist Lindsay Pereira on how anger drove him to write his new book ‘The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao’

The Hindu

Lindsay Pereira's second book, The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao, combines myth and reality to explore morality, hypocrisy, hate and faith. He questions how India, a god-fearing nation, would treat gods and goddesses if they arrived. The novel is also a political statement, inspired by the 1992-93 riots in Mumbai and the Babri Masjid demolition. Pereira believes the epic has been weaponised and that the spirit of Mumbai is actually collective PTSD. He hopes to reinterpret the epic and bring to light the injustice of those responsible for the riots never being brought to justice. Anger drives Pereira's writing, which seeks to explore the hypocrisy of communities and the destruction of his beloved city.

In his second book, The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao, Mumbai journalist Lindsay Pereira revisits both the Ramayana and the riots that tore his city apart in 1992-93. He combines myth and reality to create a book that forces up questions of morality and hypocrisy, hate and faith. “It is completely political. The reason the novel exists is because it’s also a political statement,” says Pereira about the motivation behind his book. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Over the past decade or so, there is this hyper-religious sense of where India is going. We are a god-fearing nation, but I wanted to ask myself, what if the gods and goddesses really were to arrive in this so-called spiritual nation? How would we treat them? That’s where the novel began. I was also very clear that I wanted to write about the riots in Bombay in 1992-93, because they were a very important part of my life when I was growing up in the city.

These riots were triggered by the demolition of the Babri Masjid, and the minute you talk about Babri Masjid, Ayodhya becomes critical. So the idea of merging the Ramayana with the Babri Masjid is actually inevitable, because you cannot have one without the other. The story of Lord Ram, Ayodhya, the Babri Masjid, and the riots are all so intricately intertwined that I couldn’t separate them.

The other important thing is that I feel as if the epic has been weaponised. When I was growing up, the cry of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ was perfectly okay. Today, it has extremely traumatic connotations for a significant number of people in the country. I wanted to talk about how something that is so beautiful and profound has been turned into something so completely ugly in my lifetime.

I think distance was important. It took me many years to figure out that the implications of that event were so traumatic that what everyone in India now refers to as this spirit of Mumbai, may actually just be the fact that everyone in Mumbai suffers from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). There’s so much trauma in the collective minds of people who were drastically affected by that riot, and how they must have had to cope with the fact that none of the people responsible were ever brought to justice. A number of minor players obviously did do time in jail, but the orchestrators of much of that violence, even though they were named in reports and fact-finding commissions, went on to become ministers, and their descendants continue to hold positions of power in the government. So there’s a sense of helplessness which gives way to anger, that eventually gives way to acceptance. I went through all of that myself while writing this book.

The ability to be reinterpreted time and again is critical to an epic’s ability to survive. When I was studying literary theory, one of the people we studied was the Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer, who wrote a seminal book, The Golden Bough. In it, Fraser talks about mythology and religion as moving through three cycles. It starts with magic, it goes through religious belief and eventually into scientific thought. When I look at mythology in the East as opposed to the West, I sometimes feel as if the East has never moved beyond the second stage. And that occurred to me only when I was trying to do my own interpretation of this epic. So, does it feel different to me? Yes.

I begin with politics and I try and skirt around the issue, but I can’t deny the fact that everything about the novel is political, which is why I open with that message about the Srikrishna Commission report, which has been around for a quarter of a century.