India needs to move from legalese to ‘legal-easy’ Premium

The Hindu

The continued usage of legalese is deeply entrenched in India’s legal system, affecting the layperson in accessing the legal and justice framework

Although laws regulate virtually every aspect of our daily life, they are largely unintelligible, technical and beyond the grasp of an ordinary citizen. Take, for instance, a clause inserted in the Public Examinations (Prevention of Unfair Means) Bill, 2024, which was enacted recently. Under the heading ‘Laying of rules’ it reads: Every rule made under this Act shall be laid, as soon as may be after it is made, before each House of Parliament, while it is in session, for a total period of thirty days which may be comprised in one session or in two or more successive sessions, and if, before the expiry of the session immediately following the session or the successive sessions aforesaid, both Houses agree in making any modification in the rule or both Houses agree that the rule should not be made, the rule shall thereafter have effect only in such modified form or be of no effect, as the case may be; so, however, that any such modification or annulment shall be without prejudice to the validity of anything previously done under that rule.”

Consider this provision in the Banking Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2024, which was introduced in the Lok Sabha in August 2024. It reads: if the default occurs again on the last day of the next succeeding fortnight, or, if the last day of such fortnight is a public holiday, on the preceding working day, and continues on the last day of the succeeding fortnights or preceding working days, as the case may be, the rate of penal interest shall be increased to a rate of five per cent. per annum above the bank rate on each such shortfall in respect of last day of that fortnight and last day of each succeeding fortnight or preceding working day, if last day of such fortnight is a public holiday, on which the default continues;”....

This drafting is not an anomaly. It is the standard practice and requires multiple rounds of rereading. India has over 880 central laws and several State laws. The retention of jargon in our legislation is more a matter of tradition than out of utility or necessity.

Fossilised middle and old British English terms (such as ‘notwithstanding’, ‘hereunder’, ‘whereupon’, ‘forthwith’) and Latin words (stare decisis, prima facie, actus reus, inter alia and sub judice) prevail — words that have long disappeared from everyday conversation. The continued usage of legalese is deeply entrenched in India’s legal system and the reluctance to deviate from this norm severs the layperson from the matrix of the legal and justice framework.

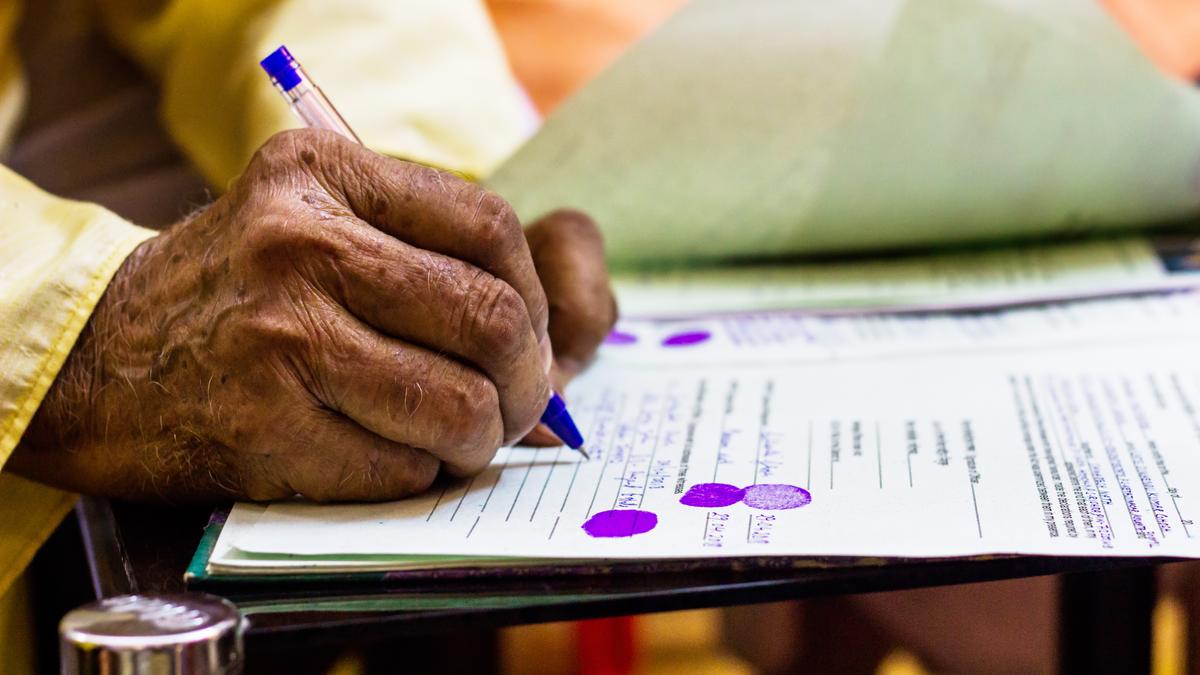

Statutes are usually replete with lengthy sentences and laden with obfuscated colonial-era terminology and incomprehensible language. Resultantly, this widens the gulf between the law and the very citizens it intends to govern and protect. Laws are perceived as a source of confusion and alienate the ordinary citizen. Archaic terminology and boilerplate clauses pervade nearly all legal texts, government communication and personal dealings ranging from laws, notices, circulars and orders to contracts, wills and deeds.

Laws are meant to regulate and serve all members of the society. However, a vast proportion of the population views laws and the formal legal system as unfamiliar and intimidating fortresses.

In a welcome move, the government recently expressed its plans to comprehensively reevaluate the existing Income-Tax Act to make it concise and lucid and to simplify taxation, enhance tax-payer services and minimise litigation.