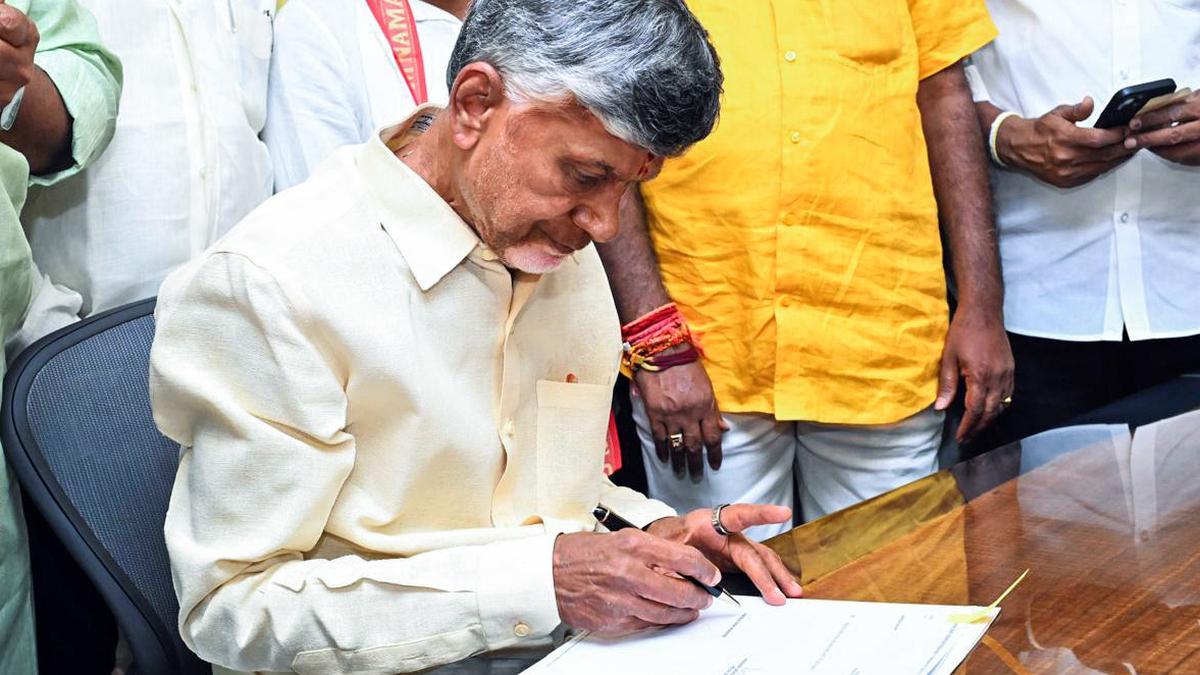

Chandrababu Naidu’s return to power and the resurgence of the idea of Amaravati Premium

The Hindu

Jagan Mohan Reddy's tenure in Andhra Pradesh marked by unfulfilled promises, debt crisis, and controversial three-capital model.

The outgoing Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, the Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party’s (YSRCP) Jagan Mohan Reddy delivered on several of what he called his “navaratnalu” — the nine welfare schemes that he promised before he rode to power with a thumping majority in 2019. The schemes ranged from interest free loans for women entrepreneurs to education fee reimbursement for poor students, but Mr. Reddy did not deliver on pressing issues like job creation, and filling thousands of government vacancies.

In a state reeling from the loss of its commercial and industrial powerhouse — Hyderabad, this appeared to be the most urgent task that he ought to have addressed. This coupled with the Mr. Reddy’s inaccessibility, and the lack of his ability to court private investments weighed quite heavily on a residual state formed in 2014, which had inherited a massive debt and had lost out on substantial central assistance that had been promised.

Mr. Reddy also threw out the plan to have a single capital at Amaravati and decided to dissipate governance into a three-capital model that was proposed by a committee set up after unified Andhra’s bifurcation, but rejected by his predecessor, Telugu Desam Party’s N. Chandrababu Naidu, who has now secured a decisive victory to form the third government since the state’s formation. The three-capital model was proposed to counter the idea of a northern power centre, nestled between the three largest cities of Andhra - Guntur, Vijayawada and Visakhapatnam. And this model came at a considerable cost.

While a lot remained undone in 2019 when Mr. Reddy took over the reins, Amaravati had a land bank of 33,000 acres with a functioning secretariat and a Legislative Assembly. Thousands of crores had been spent on a novel Land Pooling Scheme (LPS) – an attempt to circumvent the Central 2013 Land Acquisition Act. The LPS granted a 10-year lease/payment schedule for farmers whose lands had been acquired and they were allotted prime plots in the new capital’s commercial district based on how much land they had foregone.

Lush agricultural farmland’s prices soared in the emerging tri-junction of Amaravati capital region straddling across the east and the west banks of the Krishna river encircling Guntur and Vijayawada, and the upper caste Kamma vote base of the TDP made bounties selling them. This ebullience at the prospect of a spectacular new capital that people were confident would be set up under Mr. Naidu dissipated into despair as scepticism set in over the operationalisation of the three-capital model – one for legislative functions – Amaravati, another for executive and administrative functions – Visakhapatnam, and a third for the higher judiciary – Andhra’s new High Court was to come up in the much neglected and arid Rayalseema region at Kurnool in the south.

But this move faced stiff resistance by the dominant farmers of the northern Andhra region who feared a loss of economic activity. They won a case to stall the process at the Andhra High Court in Amaravati in March 2022, and the Supreme Court is yet to decide on a challenge to the High Court’s order filed by the state government. With Mr. Naidu’s return to power, it is a matter of time before the state withdraws this petition.

Andhra’s debt at the time of formation in June 2014 was ₹1,18,050 crores. This had more than doubled to ₹2,64,451 crore by March-end of 2019, and with paltry Central Assistance, the fate of a successful and flourishing new state capital, or a system of capitals, remained uncertain. As COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, progress on the capital formation, all but stalled. The state debt as on March 2023 was a whopping ₹4,28,715 crore as per an RBI report.