Blame-Woman Syndrome Premium

The Hindu

Gender Agenda Newsletter: Blame-Woman Syndrome

Last week, the Central Bureau of Investigation filed a closure report stating that actor Sushant Singh Rajput died by suicide. The news was widely reported, but there were no breathless discussions on the agency’s finding.

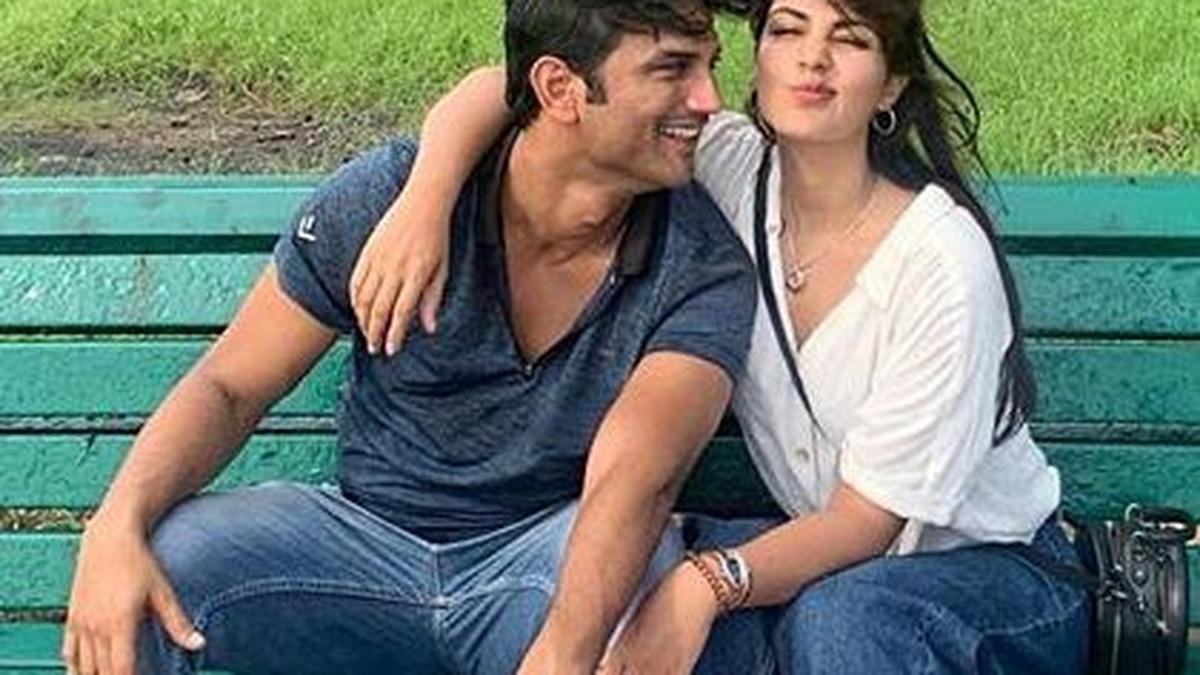

This was a far cry from June 2020, when the Bollywood actor was found dead in his apartment. Rajput’s girlfriend, Rhea Chakraborty, herself an actor, suddenly found herself in the midst of a firestorm, especially after his father lodged a complaint against her, accusing her of taking his son’s money and abetting his death. The Narcotics Control Bureau arrested Chakraborty on charges of supplying drugs to Rajput. News channels relentlessly vilified her. In an interview, the actor recalled that she was called “chudail (witch), kaala jaadu karne waali (one who performs black magic), and naagin (snake).”

The Blame-Woman Syndrome, characterised by putting the responsibility of anything that goes wrong on a woman, is all too common. As German historian Ingrid Sharp wrote in a paper, ‘Blaming the Women: Women’s ‘Responsibility’ for the First World War’, “...In Germany during and after the First World War,... women were blamed in various quarters for first failing to prevent the war and then to bring it to an end.” In an article in The New Humanitarian in 2007 on how HIV/AIDS often has more devastating consequences for Mozambican women than it does for men, Maria Cecilia de Mendonça Pedro, a sociologist, said, “When children are born with genetic problems, the mother is blamed... When the couple lacks children, the woman is blamed and the husband has the right to return her to her parents...” Whenever sexual assault cases are reported in India, someone unfailingly comes along to ask why the woman chose to step out or wear the clothes she did.

The tendency is puzzling. Women have always been regarded as the “weaker sex”. Is it not paradoxical then that the Blame-Woman Syndrome is rooted in the belief that women wield enormous power to change the course of lives and histories?

The tendency also originates from certain gendered stereotypes, which are not just pervasive, but institutionalised, as this editorial points out. During elections, for instance, despite the enormous strides that women have made in politics, slogans continue to have sexist undertones. Women, according to the unwritten but widely cited Constitution of Patriarchy, are money-grubbers, cunning, and provocative.

Women are now more financially independent and less likely to take things sitting down. This has led to uncertainty about long-established gendered roles. As an article in the Washington Post pointed out 30 years ago, “Blaming the woman offers quick relief to a society that is anxious about its future.” Fighting back tirelessly against the blame, like Chakraborty did, is the only way for women, too, to get relief and emerge vindicated.

In his novel, Deviants, Shantanu Bhattacharya captures how attitudes towards homosexuality have changed in India over the last half-century through his exploration of the lives of three gay men who are part of the same family. In an interview with The Hindu, Bhattacharya said: “I’m from a queer generation that couldn’t wait to grow up, that avoids reminiscing, and felt like it didn’t fit into groups — our stories are being told in retrospect.”

The school was established in 1981 in the car shed of a coffee planter, Parvathe Gowda. Later, the planter donated land for the school, which now boasts of a playground and a building spread over 2.5 acres. Students comprise children from nearby Krishnappa Badavane, Hospete, Sattihalli, Karehatti, Boothanakadu and a few other villages nearby.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game