An amphi-theatre has been built near Begum Akhtar’s grave in Lucknow to mark her 50th death anniversary

The Hindu

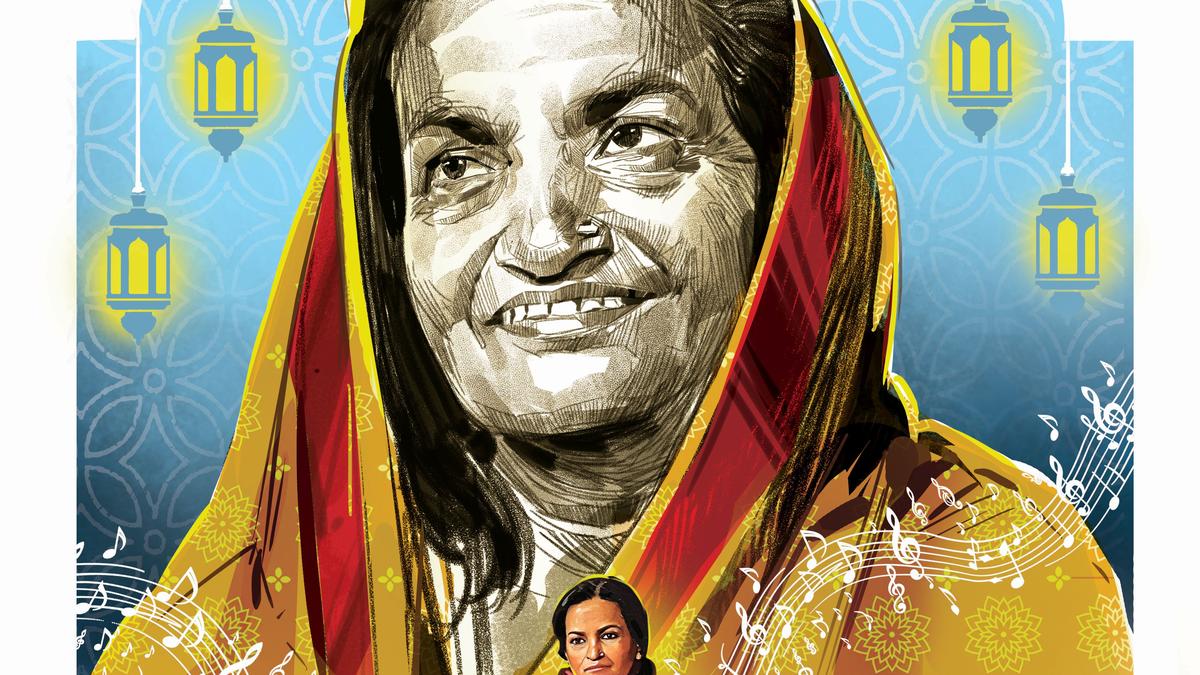

A new amphi-theatre to celebrate Begum Akhtar's life journey and her music

The travel through narrow, rickety roads to Begum Akhtar’s mazaar (grave) at Pasand Bagh in Lucknow seems to symbolise her life’s journey. The singer fought several physical and emotional battles before being crowned Mallika-e-Ghazal (queen of ghazal). Begum Akhtar possessed an unmistakable voice. It was the voice of a woman who knew pain. But she also developed early-on the strength to endure it and it came through in the way she owned the stage. It made her music so raw that she moved listeners with her honest expressions. Whether she sang a ghazal, dadra or thumri, it was all about dard, dua and dil.

When you finally arrive at the mazaar located at the corner of a squalid, congested street, you instantly get cut off from the din and experience quietude. It’s a small enclosure with bricks walls, where the Begum and her courtesan-mother Mushtari are buried — a harsinghar tree towers over their marble resting place which has their names engraved in Urdu. Graves are often seen as foreboding places but sitting by Begum Akhtar’s tombstone you feel she is calling out with her evocative ‘Hamri atariya pe aao’.

It’s been 50 years since Begum’s passing. She died on October 31, 1974. The musical icon’s fans across the globe will be delighted to know that an amphi-theatre has been built near the grave. It was launched on her death anniversary this year with a performance by ghazal singer Radhika Anand. Striking photographs of Begum Akhtar have been put up on the walls around the space and they take you through her triumphs, heartbreaks and comebacks.

A few years ago, Begum Akhtar’s grave was rescued from obscurity by her admirer and historian Saleem Kidwai, her foremost disciple Shanti Hiranand and social activist Madhvi Kukreja, whose NGO Sanatkada worked on the renovation. Delhi-based architect Ashish Thapar volunteered to execute the project. The amphi-theatre too is Sanatkada’s initiative and has been funded by Sanjiv Kumar (his father was an Akhtar fan) of the Patna-based Takshila Foundation. Madhvi is the woman behind the Santakada Festival, which celebrates the art and ethos of Awadh, a region known for its Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb that seamlessly drew from both Hindu and Islamic influences. Begum Akhtar was the foremost representative of this vibrant and syncretic culture. She was a Krishna devotee, and she used to sing about the agony of separation from Krishna in the bhajan ‘Jab se Shyam sidhare’.

From Bibbi Sayyed and Akhtari Bai to Begum Akhtar, the name kept changing as the singer struggled to find her own identity in a feudalistic society and the misogynistic world of music. She also moved cities in pursuit of her art. Though born in Faizabad, where her formal training began under sarangi exponent Ustad Imdad Khan, she moved to Gaya with her mother after being abandoned by her lawyer-father. She continued her lessons under Ustad Ghulam Mohammed Khan. She came back to Faizabad to be formally inducted into the Patiala gharana gayaki by Ustad Ata Mohammed Khan. Shifting base to Calcutta in 1927 proved to be a crucial moment in Begum Akhtar’s career. It redefined her music and personality. Her first recording by the Megaphone Record Company, which continued to be associated with her, happened in Calcutta. She also went on to act in films including Satyajit Ray’s 1958 Jalsaghar (it had music by Ustad Vilayat Khan) and perform in theatrical productions. Her first concert was organised at Calcutta’s Albert theatre by Sarojini Naidu to raise funds for Bihar earthquake victims.

The next stop was Lucknow in 1942. Here, Kirana gharana exponent Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan transformed Bibbi into Akhtaribai Faizabadi, a competent khayal artiste, in whose music the Patiala and Kirana gharanas melded seamlessly. The rise to stardom brought in the much-needed money and social status. But the singer yearned to have a family of her own. She married barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi, who put an end to her performing career. But he made it point to introduce her to the works of poets such as Ghalib, Meer, Momin, Jigar Moradabadi and Faiz. Leading a life without her passion pushed her into depression. Finally, at the advice of doctors, she decided to return to music. After a seven-year hiatus, Begum performed at the Shankarlal Festival in Delhi in 1951. It is here that she was for the first time referred to as Begum Akhtar. Her raspy and dynamic voice had now gained a soft and poignant tone.

Despite her solid grounding in classical music, Begum Akhtar chose to sing light forms such as thumri, dadra, chaiti, baramasa and ghazal. Her greatest asset was her adaptability. “She could fit herself into any musical setting,” says Satish Tanksale, a Pune-based businessman, who calls himself a devotee of the Begum. He never misses the annual ritual of visiting Lucknow on her death anniversary to offer ibadat at her mazaar. “Before it was renovated, every year, I would first clear the weeds and litter and decorate it with red roses. I would sit there for a few hours listening to her ghazals on the tape recorder I carried with me. I would break down each time, but return calmer. That’s the effect of her music,” he shares.