When industrial unrest broke out in the textile mills of Coimbatore in 1948

The Hindu

Major industrial unrest in Coimbatore's textile sector resolved after five months due to government intervention and worker strike withdrawal.

Within six months of Independence, a major industrial unrest broke out in the textile sector of Coimbatore, an industrial city in the western Tamil Nadu. Retrenchment notices were served on about 11,000 workers of mills on a single day. This triggered a strike by workers and a lockout by the management. The dispute went on for nearly five months. Thanks to intervention of Tamil Nadu Congress Committee president K. Kamaraj, coupled with the government’s assurances, the agitation was called off.

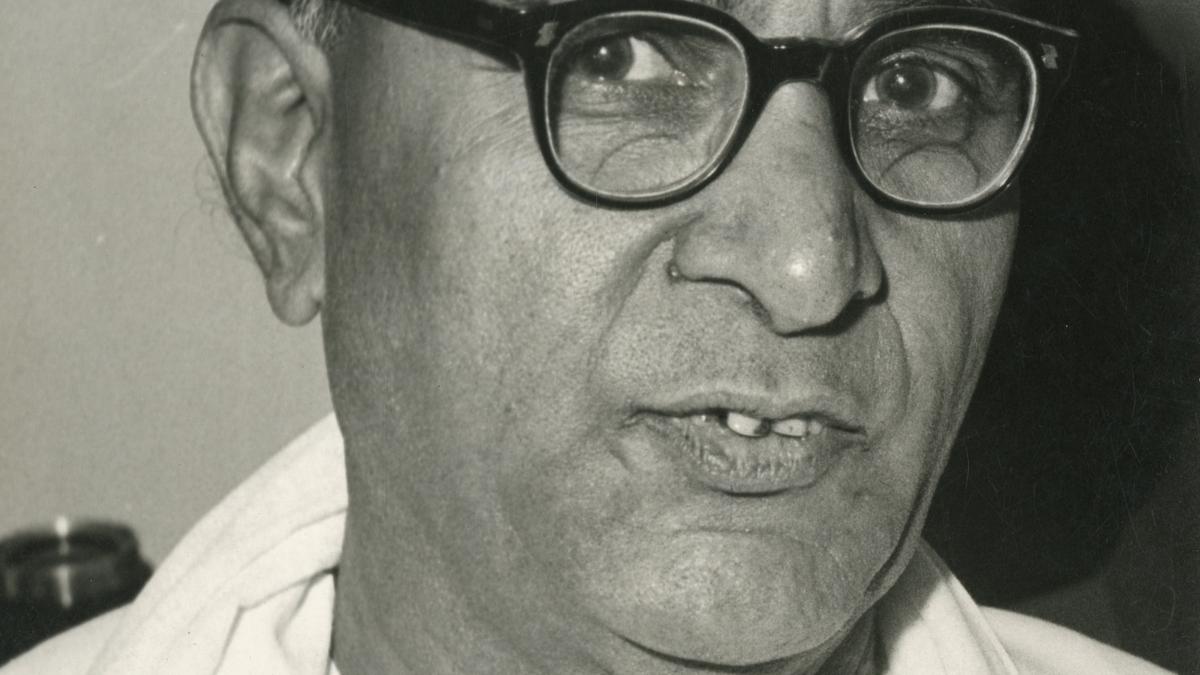

The Southern India Millowners’ Association (SIMA) highlighted the issues of the management. The case of the labour was represented by P. Ramamurti, vice-president, All-India Textile Workers’ Federation, who later became a key leader of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and G. Ramanujam, general secretary, National Textile Workers Union, who went on to head the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC). In a debate in the Assembly in June 1952, Ramamurti referred to the retrenchment issue. The Hindu, which extensively covered the dispute from January to May 1948, wrote four editorials in six months since January that year.

On the last day of 1947, the government accepted and published the Textile Standardisation Committee’s interim report that stipulated fresh workload norms. That was also a period when minimum wage was to become a reality nationwide. The Central Legislative Assembly (precursor to Parliament) adopted a Bill on minimum wages in 1946. It came into force in March 1948. It was during the intervening period that an award by the Industrial Tribunal fixed minimum wages and dearness allowance, which, according to the management, was more than double the wages earned by workers before the revision. During the Second World War, the mills had employed more workers. Once the war ended in 1945, the management concluded that additional workers were no longer needed. The mills started implementing the award in April 1947. Very soon, they found that with the number of workers they had, they could not sustain their operations. Some of them shut their operations.

It was against this backdrop that the Standardisation Committee’s report on workload prompted the management to assess that 11,200 workers had become surplus. On January 5, the retrenchment notices were put up at the mills, informing the employees that the notices would come into force on January 20. The impact was felt the next day (January 6) when workers did not turn up for the night shift, which was changed from 8 p.m. to 7 p.m. Initially, it was thought that the workers were upset with the advancement of the night shift by one hour. The Labour department advised the mill owners to revert to the original time. As the workers did not relent, the management realised that the real cause of the strike was the retrenchment. In a release issued on January 9, the SIMA said, “The mill owners have assured the Government and the labour leaders that all possibilities of re-employing as much of surplus labour as possible by working an extra day in the week or an extra shift, wherever possible, will be explored.”

As the problem escalated, the government tried to mediate. But, on January 20, it announced the failure of its efforts at a compromise. It gave an account of the situation in 11 mills: in nine, workers declined to do other than what they did earlier; in one, there was a sit-in; and in the other, no work was possible. Three days later, the matter came up for discussion in the Assembly. Industries Minister H. Sitarama Reddi held labour leaders responsible for the trouble, saying they were unwilling to accept the committee’s recommendations. On January 27, the management of 27 mills declared a lockout in line with the decision taken at a meeting of the SIMA two days earlier. The owners of the mills in Salem and Tiruchi followed suit.

The impasse continued for two months and a dozen workers staged a demonstration once before the Assembly chamber at the Secretariat. On March 20, the government asked the mill owners to resume their operations in two days, as sections of the workers wanted to return to work. The owners responded favourably, but not all the workers went back. The SIMA clarified that as 9,250 out of the 11,200 workers had been promised re-employment, the “net retrenchment” was 1,950 persons, who were hired to meet the war time needs and “not directly connected with the industry at all”. In the meantime, the workers’ cause found sympathy with a think tank, Indian Institute of Current Affairs, which constituted a panel of its own to study the problem. The Institute urged the government to keep in abeyance, “in the interest of labour and the public”, the standardisation scheme for reconsideration by a new committee.

Kamaraj, who stayed in Coimbatore for two days in early May, met representatives of the two sides. Subsequently, he called upon the government to modify the revised workload and the workers to resume work. The workers then announced the withdrawal of their strike. The government stuck to the stand that the revised workload should be given a fair trial and if there were difficulties, it could be revised suitably. Most of the mills started a third shift and, in fact, reported shortage of hands initially. The owners also set up the ‘re-employment exchange’ for the unemployed. All these developments brought the crisis to an end.