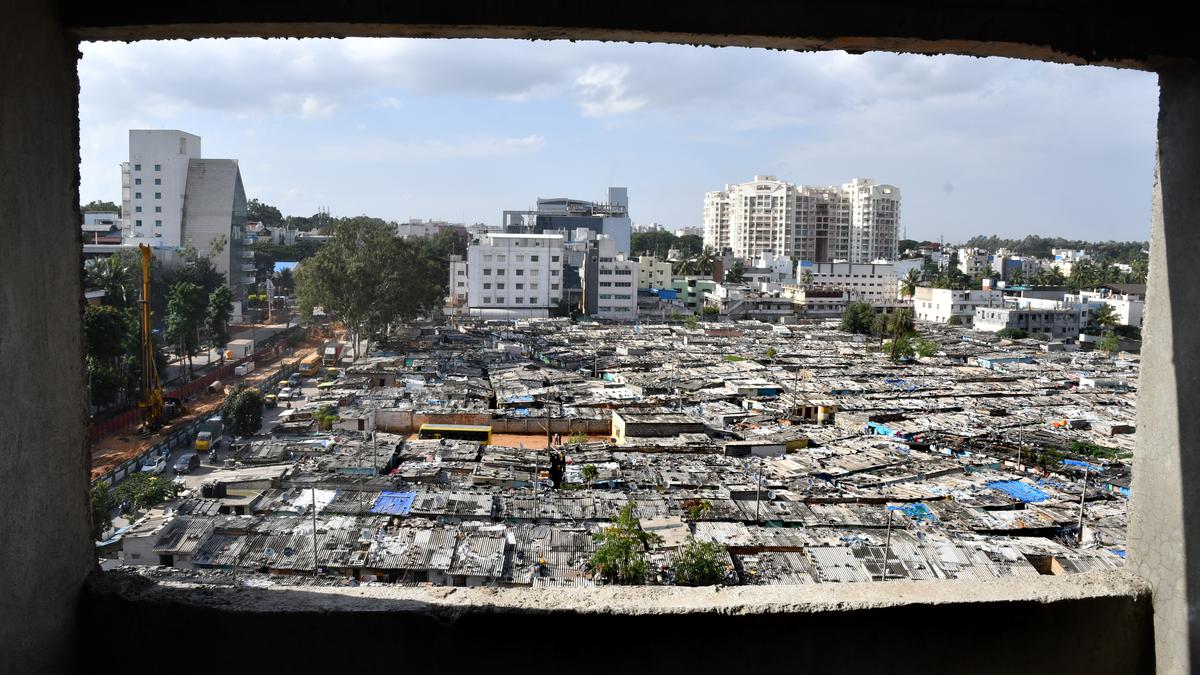

What has the city built for those who have built the city? Premium

The Hindu

Before 1982, a slum inhabited by 64 families occupied the space where the M.S. Building now stands in the heart of Bengaluru. In that year, the slum was relocated to government land in Laggere village. The residents were primarily from North Karnataka and predominantly worked as masons in the city.

Before 1982, a slum inhabited by 64 families occupied the space where the M.S. Building now stands in the heart of Bengaluru. In that year, the slum was relocated to government land in Laggere village. The residents were primarily from North Karnataka and predominantly worked as masons in the city.

Shambanna, a local resident, recalled that back then he attended the school located inside the premises of the Governor’s House that was close by. However, after they were relocated, they had to walk to Mahalakshmi Layout to catch a bus to school. “Soon after we moved, there was a bus strike, leaving my younger brother and me stranded without a means to return home. This incident frightened our parents, and they didn’t allow us to continue attending school. That’s why I work as a mason today,” he said.

Back then, the area they were relocated to had no accessible roads leading out of the slum. “Whenever we needed to buy something, we had to walk one and a half kilometres to Laggere Village. To catch a bus, we had to walk to Peenya or Mahalakshmi Layout, both far from our area. The Ring Road was constructed only in the year 2000. Despite subsequent developments, we still have to reach the main road to find autos or buses. There are no roads allowing ambulances to access our area,” bemoaned Shambanna.

The slum adjacent to Poornima Theatre was also relocated to Laggere in 1986. People from the community, however, still maintain a strong connection to the old neighbourhood. Every day, many of them commute from Laggere to Poornima Theatre for work. Women arrive in tempo vehicles to work in houses, offices, and marriage halls near Poornima Theatre, returning to Laggere in the same vehicles at the end of the day.

In yet another instance, the Railway Department demolished three slums near Padarayanapura Railway Track in 2002. Following prolonged efforts, the affected people were allocated plots measuring 15x20 in Singapura. According to Syed Afsar, a 50-year-old local leader, the residents struggled to find employment opportunities in the new neighbourhood. There are only two buses to the market from their area — one at 7 a.m. and another at 9 a.m. Missing these buses means missing out on a day’s wage as reaching after 11 a.m. makes it challenging to secure work. The last bus returning from City Market departs at 7.30 p.m., and one would need to spend the night on the streets upon failing to catch it.

Consequently, more than half of those who received plots from the Slum Board reverted to their rental homes. The area lacks a Government Hospital or specialised medical facilities for emergencies. In case of a medical emergency, individuals have to travel approximately 11 kilometres to K.C. General Hospital in Malleshwaram. There have been no instances of calling for an ambulance during emergencies. Instead, residents rely on available auto-rickshaws to reach hospitals.

Jyoti, a resident of the area, said, “During my delivery, I struggled to find transportation and ended up going to Bowring Hospital in an auto, which cost us ₹500. However, upon reaching the hospital, I was informed that the delivery couldn’t be conducted there. I had to be transferred to Vani Vilas Hospital in an ambulance. The only hospital near Sadaramangala is K.R. Puram Hospital, but there’s uncertainty about the availability of doctors at the time one visits.” Another resident recalled an incident where a woman gave birth in an auto while commuting from the area.