The urgent need for data to make personalised medicine equitable Premium

The Hindu

Warfarin's risks and benefits vary across populations due to biased medical research and lack of genetic diversity in studies.

Warfarin is a powerful blood thinner and a leading drug for cardiovascular disease worldwide. But in South Africa, it is among the top four drug varieties leading to hospitalisation from adverse drug reactions. It’s reasonable to suppose that the drug has similar problematic effects farther across sub-Saharan Africa, though the national data needed to show it are lacking.

The fact that warfarin is riskier in some populations than others isn’t a surprise. Different geographic regions tend to host people with slightly different genetic makeups, and sometimes those genetic differences lead to radically different reactions to drugs. For certain people, a higher dosage of warfarin is fine; for others, it’s dangerous. Researchers have known this for decades.

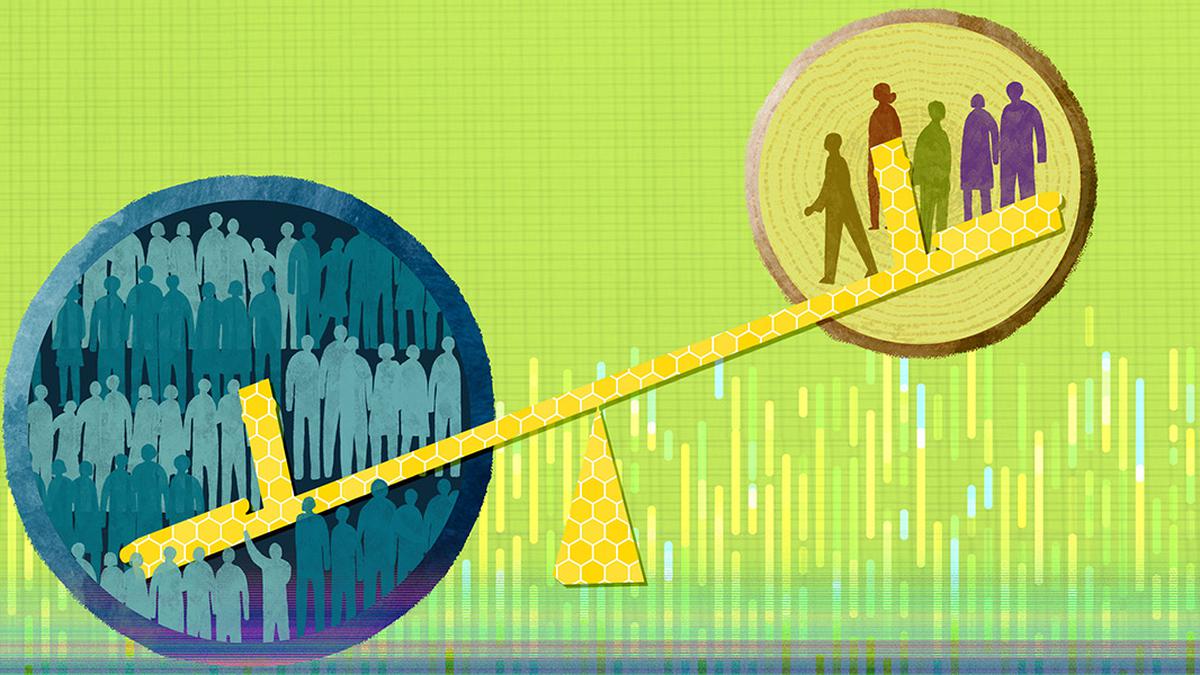

The problem is that the majority of medical research, including genetic research, is still done mainly on one subset of the world’s population: men of Northern European origin. This means that negative drug-gene interactions in other, less well-studied populations can fly beneath the radar. In the case of warfarin, one study concluded that using someone’s genetic information to help guide their drug dosing would benefit 18% to 24% of people categorised as white, but have no benefit for people identified as Black, Chinese or Japanese.

While that study is a decade old, the general point still holds true: A bias in our current understanding of the genetics of different populations means that some people would be helped far more than others by genetically informed personalised medicine.

As a bioinformatician, I am now focusing my attention on gathering the statistics to show just how biased medical research data are. There are problems across the board, ranging from which research questions get asked in the first place, to who participates in clinical trials, to who gets their genomes sequenced. The world is moving toward “precision medicine,” where any individual can have their DNA analysed and that information can be used to help prescribe the right drugs in the right dosages. But this won’t work if a person’s genetic variants have never been identified or studied in the first place.

It’s astonishing how powerful our genetics can be in mediating medicines. Take the gene CYP2D6, which is known to play a vital role in how fast humans metabolise 25% of all the pharmaceuticals on the market. If you have a genetic variant of CYP2D6 that makes you metabolise drugs more quickly, or less quickly, it can have a huge impact on how well those drugs work and the dangers you face from taking them. Codeine was banned from all of Ethiopia in 2015, for example, because a high proportion of people in the country (perhaps 30%) have a genetic variant of CYP2D6 that makes them quickly metabolise that drug into morphine, making it more likely to cause respiratory distress and even death.

Researchers have identified over a hundred different CYP2D6 variants and there are likely many, many more out there that we don’t yet know the impacts of – especially in understudied populations.