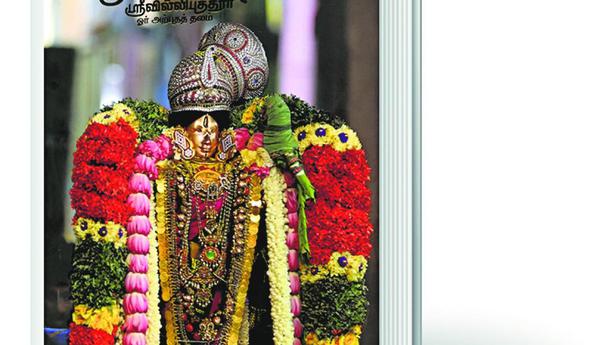

Stories from Srivilliputhur

The Hindu

Chithra Madhavan’s book presents different aspects of Andal and the town

India’s temples are living receptacles of legend and history, art and architecture, tradition and heritage, beauty and pageantry. They have long been the centres of religious as well as social life, binding individuals and communities in a collective consciousness. In the absence of proper documentation, information about these ancient structures is mostly scarce, except for those thin booklets published for tourists and devotees.

In this light, historian-scholar Chithra Madhavan’s book, The Splendours of Srivilliputtur (Universal Publishing) is significant.

Published in English and Tamil, it has articles by scholars and experts that focus on various aspects of this temple. Chithra’s essays on the legends, festivals and architecture of the temple of Andal and Vatapathrasayee, and on the Vaidyanatha Swamy temple in the adjacent village of Madavar Vilagam are interesting accounts.

Prema Nandakumar, multilingual scholar and expert on Vaishnavism, explores Andal as an incarnation, as one of the Azhwars, who propagated the Bhakti Movement in Tamil Nadu, and has selections from her and her father Periyaazhwar’s immortal poetry. The chapter on Andal’s wedding, written by Prema, refers to the epic poem, Amukta Malyada, in Telugu, composed by emperor Krishnadevaraya of the Vijayanagara kingdom; and to Nachaaru Parinayam, another poetic work in Telugu, composed for Yakshagana by a group of writers from Rajapalayam. She also talks about Araiyar Sevai, the singing of the pasurams (hymns) with abhinaya by male members of the families that are hereditary performers of this ritual, and highlights its artistic aspects and history. G. Sankaranarayanan, also a multilingual scholar, writes on the inscriptions in the temple, dating to the 10th century. The Chola inscription mentions the name of the village as Vikrama Chola Chaturvedimangalam. Details of endowments by Pandya and Chera kings and the Nayak rulers to the temples of Sudikkoduththa Nachiar, Vadaperunkovil Swamigal, and Periyazhwar are mentioned.

Historian V. Sriram writes on the compositions on Andal and finds only a few over the centuries, among them are ‘Choodi koodi nacchari’ by Tallapakka Annamacharya and songs on Andal by the 20th century composer Ambujam Krishna. The courtesan Muddupalani of Thanjavur had translated Andal’s Thiruppavai into Telugu in the 18th century. Ariyakkudi Ramanuja Iyengar was asked by Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi, 68th head of Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Pitam, to set the Thiruppavai to music and he sang them all at the temple in 1952. Sriram also writes about the Shiva temple at Madavar Vilagam.

Asha Krishnakumar’s article is about the parrot that Andal holds in her hand and how it is made afresh every day with leaves, banana fibre, and the skin of pomegranate by the same family over the years. She explores the bird’s symbolism, the legends associated with it, and its spiritual significance.

The prasadam, special to each temple and the recipe handed down through generations, ensures no visitor goes hungry. Rakesh Raghunathan gives a list of the prasadams offered daily and those prepared on festival days at the Srivilliputhur temple.