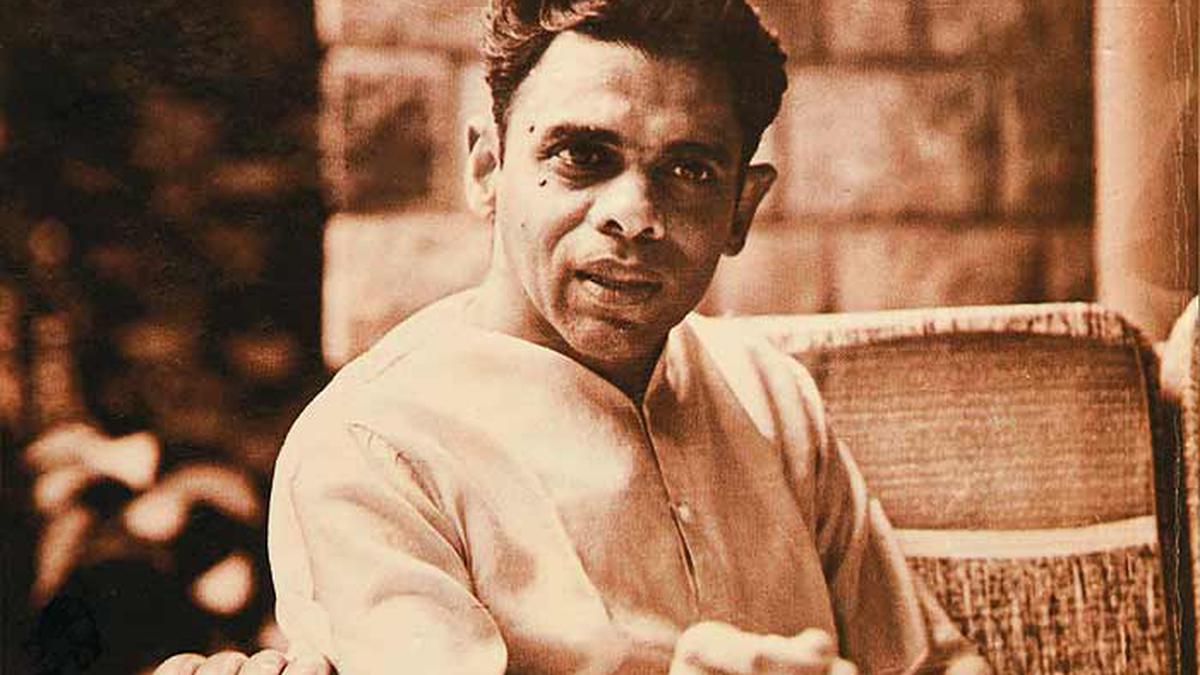

Not the same Ramanujan | Review of ‘Soma’, edited by Guillermo Rodriguez and Krishna Ramanujan

The Hindu

Soma, an anthology of A.K. Ramanujan's mostly unpublished poems, edited by Guillermo Rodriguez and Krishna Ramanujan, offers readers an opportunity to explore the poet's fascination with the Soma plant. Contextualised by two essays, the book reclaims and records a critical moment of literary history. The poems, while not unselfconscious, require a different reader, one willing to be unsettled and travel with Ramanujan to an unknowable place. The anthology is a remarkable achievement, a moment in Ramanujan's oeuvre that threads together his work as a translator and poet.

For all those who love A.K. Ramanujan’s work, for all those who walk around with lines from his poems and translations in their heads, Soma is an invaluable resource and a delight.

Edited by scholar Guillermo Rodriguez and Ramanujan’s son and science writer Krishna Ramanujan, this book brings together the poet’s mostly unpublished ‘Soma’ poems, numbering 22. Drawn from the A.K. Ramanujan papers at the University of Chicago, the poems constitute rich archival material and offer the reader an opportunity to excavate from discarded poetry drafts, another Ramanujan altogether — one who between the 1970s and the early 80s was fascinated by the Soma plant. We might want to read Soma together with Journeys: A Poet’s Diary (2019), edited by the same duo, which describes the poet’s experiments with mescalin.

Believed to have magical, consciousness-altering properties, the elixir from the Soma plant was supposedly consumed by Hindu gods and by priests during rituals. The drink was also personified by a god of the same name. Contextualising Ramanujan’s ‘Soma’ poems are two essays. The first of these, by Krishna Ramanujan, titled ‘Hummel’s Miracle: The Search for Soma’ outlines the importance of the Soma drink for vedic priests and provides a history of the plant and its relationship to the poems.

The second essay, by Rodriguez, describes Ramanujan’s own approach to and understanding of Soma and how this feeds into his poetic process. The editors have also included, by way of additional material, a reprint of an essay by Wendy Doniger — ‘The Post-Vedic History of the Soma Plant’ — first published in 1968 as well as an interview with Ramanujan conducted by the poet and scholar Ayyappa Paniker in Chicago in 1982.

Poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra says in his foreword: “To have left [the Soma poems] interred in boxes in a library would have meant, among other things, losing a critical moment of our literary history.” And indeed, that is the point of the book — to reclaim and record this particular version of Ramanujan for literary history. The book achieves this task remarkably well, and even though 22 poems (many of which were discarded drafts) may not seem like a lot, collectively they represent a moment in Ramanujan’s oeuvre. They also thread together his work as a translator of Nammalvar and as a poet writing in English.

As Rodriguez points out in his essay, Ramanujan, ever since his immersion in Virasaiva bhakti poetry, believed that grace was required for poetic inspiration. The ‘Soma’ poems, while not entirely unselfconscious, do sing to us from a different place than Ramanujan’s other poems. They also require of us a shift in how we read Ramanujan, demanding a different reader, one who is willing to be unsettled by the Ramanujan she encounters, willing to travel with him to another, unknowable place. The first of the poems opens with the lines:

Soma is restless.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game