‘Kohrra’ series review: Landscape in the mist

The Hindu

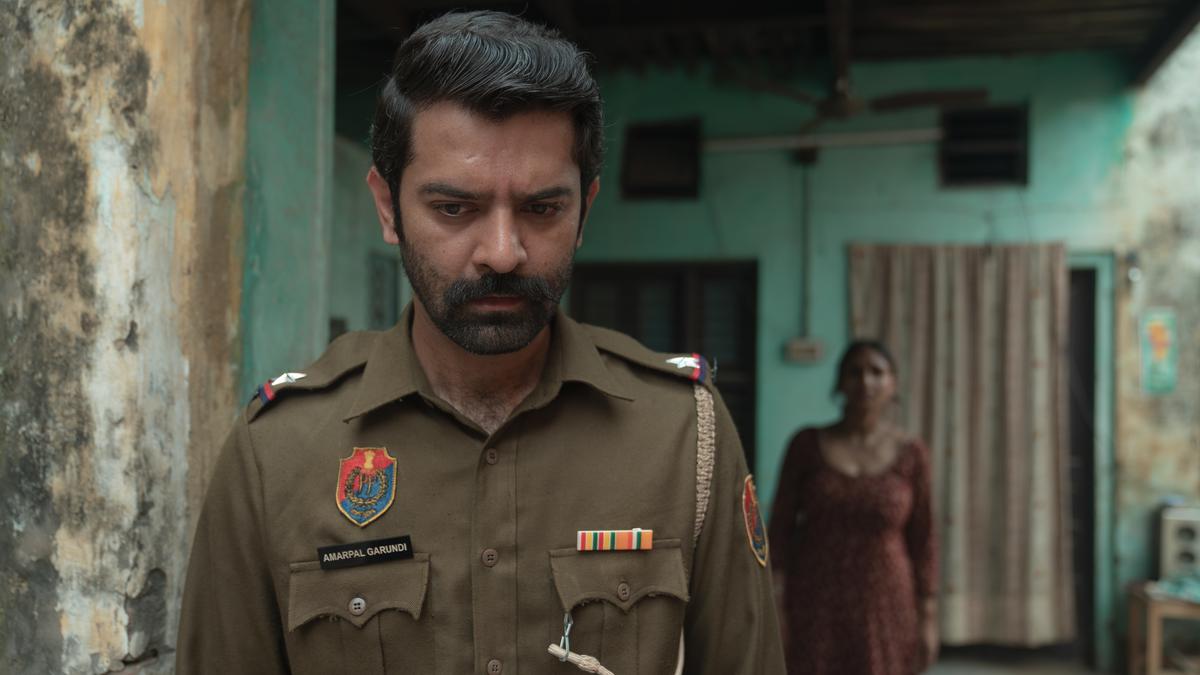

Suvinder Vicky and Barun Sobti lead a fine ensemble in this dark investigative series kicked off by an NRI’s murder in contemporary Punjab

Like Memories of Murder (2003), Kohrra opens on a vast, verdant field. A body is discovered by the wayside. We get an exchange between a stunned young boy and a small-town cop. The forensic unit is late to the crime scene, the local media is early —ironies recognisable from Memories. Randeep Jha is a young filmmaker and it makes sense he would want to pay tribute to the iconic opening of Bong Joon-ho’s great thriller. In fact, the only major departure I noticed is the overall gloominess of the scene, the camera refusing to tilt up to admire the sky and the clouds.

Co-created by Sudip Sharma, Gunjit Chopra and Diggi Sisodia, Kohrra is short on clouds or silver linings. From the start, the series on Netflix, true to title, comes shrouded in mist and mystery. Paul Dhillon (Vishal Handa), a moneyed NRI, is found slain in the Punjab countryside, his throat slit and head bludgeoned with a hard, blunt object. Paul was visiting his hometown of Jagrana for his wedding; his best man, Liam, a British national, is now missing. Investigating the whole matter are two mid-tier cops, SI Balbir Singh (Suvinder Vicky) and his partner Amarpal Garundi (Barun Sobti). Like Chacha Chaudhary and Sabu, they make a fair team: the aging Balbir is calm and watchful; Garundi extracts information by grabbing people by the sack.

Over the next few episodes, Balbir and Garundi clumsily accost a bunch of suspects. There’s a sulking rapper who was involved with Paul’s fiancée; an absconding bus driver; two truckers and a local junkie. Their subsequent torture in police custody will remind viewers of Paatal Lok(2020), which pirouetted across half the map of north India and took in characters from all demographics. Kohrra, by contrast, stays calmly put in one place, homing in on a cloistered community and its interpersonal dynamics. Balbir’s daughter has left her husband and moved back into her parent’s house with her young son; she holds Balbir responsible (perhaps not so indirectly) for her mother’s death. Paul’s father, Steve (Manish Chaudhari) — his Indian name is revealed to be ‘Satwinder’ — is feuding with his brother over land. Land is also the mucilage in the odd incestuous relationship between Garundi and his sister-in-law, who does not want him to get a wife and thus upset their domestic arrangement.

Recent police procedurals like Delhi Crime, Dahaad and even the satirical Kathal have highlighted how technology can both aid and impede an investigation. Balbir and Garundi make an important deduction from Facebook; elsewhere, a viral video gets in their way. In a blackly comic detail, Paul’s phone cannot be accessed via Facial Recognition because, as Garundi drily says, his face has been badly disfigured. These nods to modernity offer a vivid contrast to the parochial values and prejudices at play. Though separated by power and class, Balbir and Steve are violent, oppressive patriarchs linked by pride. “We are a warrior race,” Steve fumes at Paul in a flashback. In one telling scene, a son’s misguided attempt to win his father’s affection is repaid with the gift of a gun.

Kohrra, quite admittedly, lacks the politics and sprawl of Paatal Lok, which took stock of a nation on the boil. Recent Indian web shows have fought shy of controversy, and Sharma and his writers too err on the side of caution. The several scenes of police brutality flit by without comment, as does a regionalist slur spewed by one character against another. But certain micro, Punjab-specific issues ring loud. Balbir is pressured to wrap up the case by his higher-ups, who tell him to pin it on the junkie and call it a day. The implication is that in a state riven by drugs and gang violence, larger and deeper realities will get buried. “Know what is the tragedy of our Punjab?” Balbir asks Garundi. “...that we don’t confront the truth.”

Balbir, drunk and disillusioned, is brought to disturbing life by Suvinder Vicky. The Punjabi actor — known for Milestone and Chauthi Koot — can work wonders with that hangdog face, an expressive paunch, and little stretches of his limbs and neck. There is a great moral tentativeness to his performances, which makes even the most predictable characters unpredictable. He is paired well with Sobti, who finds a kind of coarse comedy in his character’s boorishness. His Garundi has a touch of Aamir Khan... if Aamir Khan could ever get his Punjabi characters right. Manish Chaudhari (menacing in turban and white beard), Varun Badola, Harleen Sethi and Amaninder Pal Singh are all perfectly cast, and it’s thrilling to see Rachel Shelley back in Hindi cinema. It is a wicked ploy; returning to India two decades after Lagaan, she finds nothing but death and devastation.

The series is sharply and impressively shot. Cinematographer Saurabh Monga captures some memorable static frames: a samosa gone stale on a copper’s desk, dark smoke billowing from an electric incinerator. Given the slow-burn of the plot, Jha occasionally revs up the pace with a set of forgettable chases. He could also have avoided the heavy-handed dream sequences to emphasise guilty minds and stricken hearts. For some reason, it’s not enough to have ‘love is a dog from hell’ written on a character’s wall; we also hear Balbir mutter a variation on the line. It’s a decent aphorism to sum up the show, but perhaps Kohrra needed something else. I will settle for a different line, uttered by Garundi to one of his detainees, casually but from the heart: “Sorry, yaar.”