It’s clear now: iron inside the sun is more opaque than expected Premium

The Hindu

Discover how iron's opacity in the sun challenges scientific models, and how researchers are working to resolve the discrepancy.

The world is full of mysteries but not all of them are grand. Sure, we don’t know what the mind really is or what the inside of a black hole looks like. But there are also many mysteries hiding in the little details.

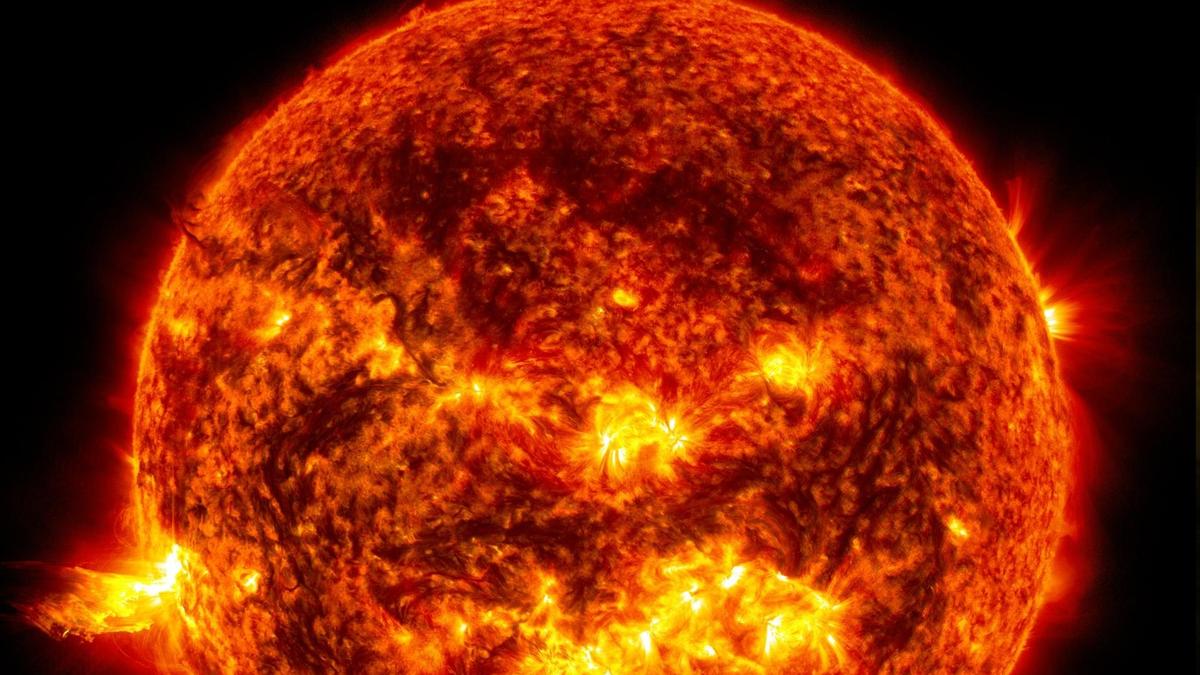

For example, we don’t know why iron inside the sun is so opaque.

Solid iron objects are everywhere around us. They’re used to make doorknobs, cooking utensils, furniture, water tanks — all sorts of things. And they’re all opaque. When light hits an iron object, it can’t pass through. Instead, some of it is absorbed and some of it is scattered. How much light an object absorbs is called its opacity: the more it absorbs, the more opaque it is.

Iron’s opacity isn’t an important detail when making a doorknob but when we’re talking about the sun, the implications are practically cosmic.

The universe’s engines

The sun is the star closest to the earth and thus the one humans have studied the most. A lot of what we know, or think we know, about different kinds of stars comes from studying the sun.

This is true on two levels. First: scientists have developed various theories to explain the sun’s properties. Over many decades, they pointed telescopes, detectors, and antennae at emissions from the star to capture electromagnetic radiation, charged particles, heat, etc. and compare the data with each theory. Then they eliminated theories that disagreed with the data and refined those that did.

A new electrochemical technique published in the journal Nature Catalysis now proposes to separate urea from urine in its solid form via a greener, less energy-consuming process. This method converts urea, a nitrogen-rich compound in urine, into a crystalline peroxide derivative called percarbamide.