India’s citizenship laws: The Constituent Assembly dilemma Premium

The Hindu

India's complex journey to define citizenship post-independence, exploring the impact of Partition and religious identity on belonging.

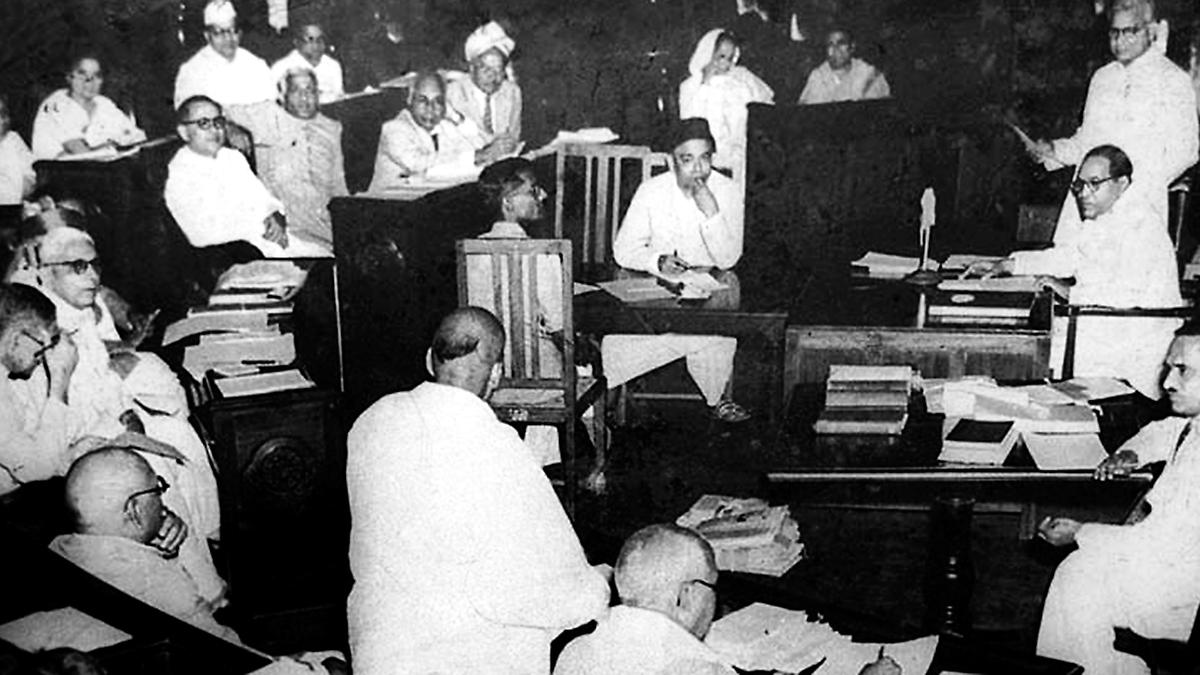

When lines are drawn and land violently cleaved apart, new questions are asked. Who belongs where? And how does one articulate this nature of belonging? After India won a hard-fought independence in 1947, this conundrum fell to the Constituent Assembly in August 1949. The Partition had triggered waves of migrations across India’s western and eastern frontiers; many Indians also lived abroad, sometimes in difficult conditions. It was imperative to discuss citizenship and define the notion of an Indian Citizen. All articles related to citizenship “received far more thought and consideration during the last few months than any other article contained in this Constitution,” India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru remarked, standing tall in the circular Central Hall, on August 12. The Constituent Assembly would debate, deliberate and dissent over citizenship and minority rights. In the face of anxiety over migration and a perceived threat from “illegal immigrants,” some saw religious identity as the rightful determinant. But consensus then deemed this was a discriminatory yardstick, and citizenship by religion was put to bed.

The path of citizenship has since wended its way through numerous circuitous routes, but returned to this contentious point of origin. The new Citizenship Amendment Act fast-tracks naturalisation for non-Muslim religious minorities fleeing neighbouring countries. On May 15, the Union government on Wednesday granted citizenship certificates to more than 300 people who applied under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, marking the first such naturalisation under the new Act. Religion, among other things, will decide who gets to be a citizen in today’s India. The river of time has also carried forth fragments of arbitrary deadlines and cutoff dates, regulated through somewhat opaque tribunals and bureaucrats.

In this first part, The Hindu revisits the paper trail and Constituent Assembly debates that presented an early definition of the idea of belonging in India.

Think of the colonial rule in two phases: when India was governed by the East India Company between 1757 and 1858, and when the Crown officially took over, extending its imperial arms from 1858 to 1947. In the first phase, there were no official citizenship laws, noted historian Arun Sinha in the journal Law of Citizenship and Aliens in India. Whatever Acts the British had granted rights to ‘British subjects.’ Did people living in India count as British subjects? It is unclear; there was uncertainty at the time if the definition applied only to European British subjects or to native Indians too.

The first official citizenship law was crafted in the second phase of the colonial rule. The mainland was split two ways: British India covered 54% of the territory and included 70% of the population, whereas the princely states governed by local princes and feudal lords enjoyed a degree of autonomy. The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act, 1914, was codified to confer rights to ‘national-born British subjects’ and those who obtained naturalisation certificates from colonial officials. People born on the British mainland or to British parents were given a higher status than people born in the British colonies. Put differently, people of Indian descent received a “second-class citizenship,” Mr. Sinha noted.

Independence allowed India to consider and conceptualise the notion of citizenship for the first time. This conversation was complicated by two factors: the flow of migration on India’s eastern and western frontiers, and a looming anxiety over security and identity. Sri Prakasa, India’s High Commissioner in Pakistan, acknowledged the unique position, noting on April 12, 1948, that “Partition is such a novel thing... that we have been unable to adjust ourselves psychologically with the new situation and many people, particularly the minorities have been unable to adjust ourselves psychologically with the new situation and many people...”

The boundary lines of Bengal, Punjab and Assam saw mass migration on both sides. About 10 million people moved across the boundaries in the first year, according to government census figures. This figure crossed 20 million by the 1960s. On the western frontier, between West Pakistan and India, the movement happened in two waves: first came the Hindus and Sikhs who chose India as their home; the second wave comprised largely of Muslims “who had left their homes in the initial months of the Partition — or, often, fled in fear of their lives — to travel to West Pakistan, but found the new nation less than ideal,” scholar Manav Kapur pointed out in a paper. Mr. Nehru’s government had expressed concern about the “exodus” of Hindus from East Bengal and Eastern Pakistan due to reported harassment and fears; urging them to not leave their homes and hearths. If this was not checked immediately, “the two Dominions would be faced with another serious problem which might prove beyond their control,” he said, according to an April 6 report published in The Hindu. Regarding discrimination faced by Muslim refugees in Delhi, Mr. Nehru said they would be administered “fair treatment”: the “Indian State was a secular state”, and the government “would welcome [Muslim] refugees back to Delhi if they returned,” to ensure fair treatment.