How K. G. George’s women characters immortalise the late director’s cinematic brilliance Premium

The Hindu

Even decades after K. G. George’s last film, his memorable female characters continue to resonate, reminding viewers of the enduring impact of his cinematic legacy; he redefined Indian cinema by crafting complex, resilient, flawed and relatable female characters who challenged societal norms

Auteur KG George was an iconoclast, a filmmaker who broke templates that dominated Malayalam cinema in the 60s and early 70s. Walking ahead of his time, the nine-time winner of the Kerala State Film Award explored subjects, themes, characters and narratives that were new to Indian cinema. However, what made his films a class apart was his astonishing range of female characters.

His on-screen women were flawed. But, like the Japanese art form of Kintsugi that believes a repaired pot is stronger and increases in value, the women in George’s films emerge stronger and more resilient as a result of their traumas and experiences. Their flaws make them raw, real, relatable and memorable, immortalising them in the hearts of cineastes. Broken, manipulated and dominated by a chauvinistic, patriarchal world, the women gaining strength and agency is a powerful expression in many of his movies.

Adaminte Vaariyellu (Adam’s Rib, 1984), one of the best in his oeuvre, explores the psyche of three women from different socio-economic backgrounds. What binds the three women — Alice, Vasanthi and Ammini — is the oppression they are subjected to in a chauvinistic society. Whether it be the defiant Alice (Sreevidya), the dutiful Vasanthi (Suhasini) struggling hard to juggle her work at home and office, or the sexually exploited Ammini (Surya), all three are manipulated and abused by the men in their lives. It is only Ammini who seems to rebel and rise against the oppressive structure. Was he hinting at an uprising that is triggered by the impoverished masses who are not bound by the mores of middle-class morality and niceties?

Vasanthi’s drudgery in the kitchen and at home was a first for Malayalam cinema, which still romanticises the gendered politics in the kitchen and the home. George turned his lens to reflect the mindless grind that women had to go through at home, no matter how accomplished they were.

This theme of the home as a domestic haven was busted by George in several films. Mattoral (1988) stands out for its unfiltered view of the suffocating ambience and ennui in a typical middle-class home. Kaimal (Karamana Janardhanan) is the quintessential provider. His home is the typical middle-class universe where his wife Susheela is a dutiful homemaker, looking after her husband and their two children, all at the cost of her dreams and desires. The sheer boredom and silence in the marriage persuade viewers to look at the idealised home through a critical lens. Matters come to a head when Susheela elopes with Giri, a mechanic.

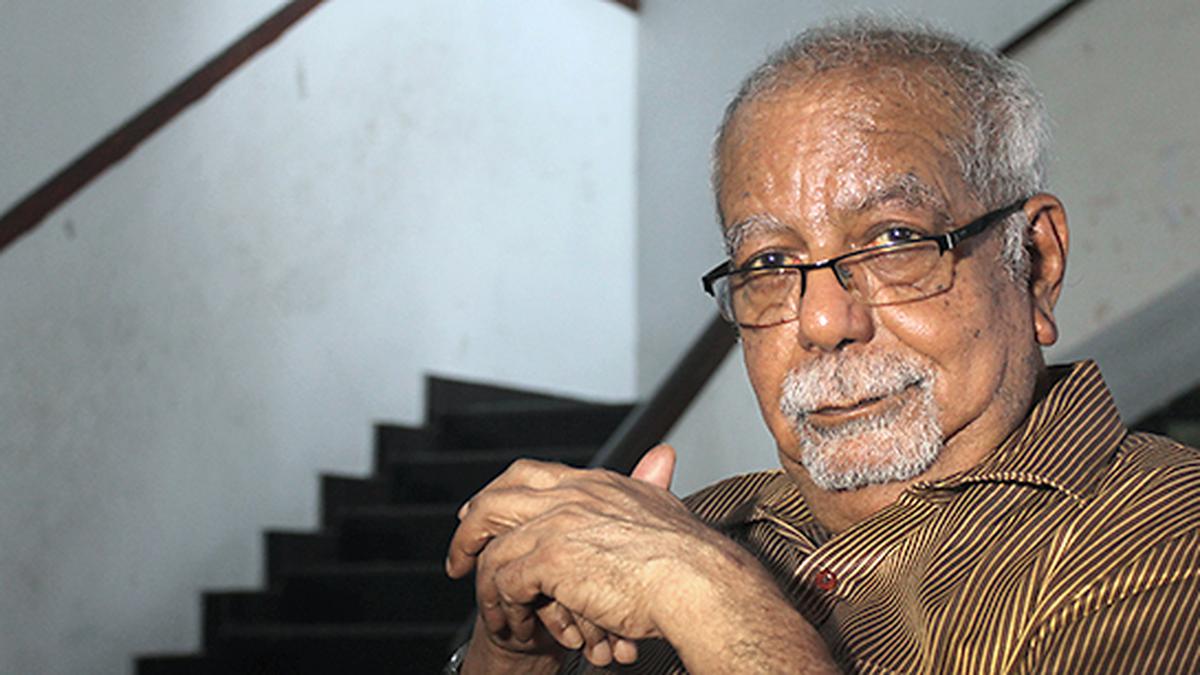

George, who passed away on Sunday at the age of 77, has given Indian cinema some of the most complex, intriguing women drawn from different strata in society. His cinematic world was filled with women with needs – emotional, physical, psychological and sexual. Not afraid to vocalise their needs or seek those outside the conventional societal norms of marriage and family, the women led the way for latter-day directors and scenarists to invest in reel women.

For instance, Annie (Sreevidya) in Irakal (1985), the only daughter in a harsh, feudal family in Central Kerala, is a deviant who seeks sexual favours from the men she fancies. Annie is neither apologetic nor embarrassed about her adventures. In fact, she exemplifies the selfish, rapacious family she belongs to. The dark psychological thriller about a cold-blooded killer in the family has spawned many clones but none could match the brooding fear and suspense of the original that also became a metaphor for the dark days of the Emergency.