How courtesans were not merely entertainers but cultural and political influencers

The Hindu

A peek into the lost world of tawaifs

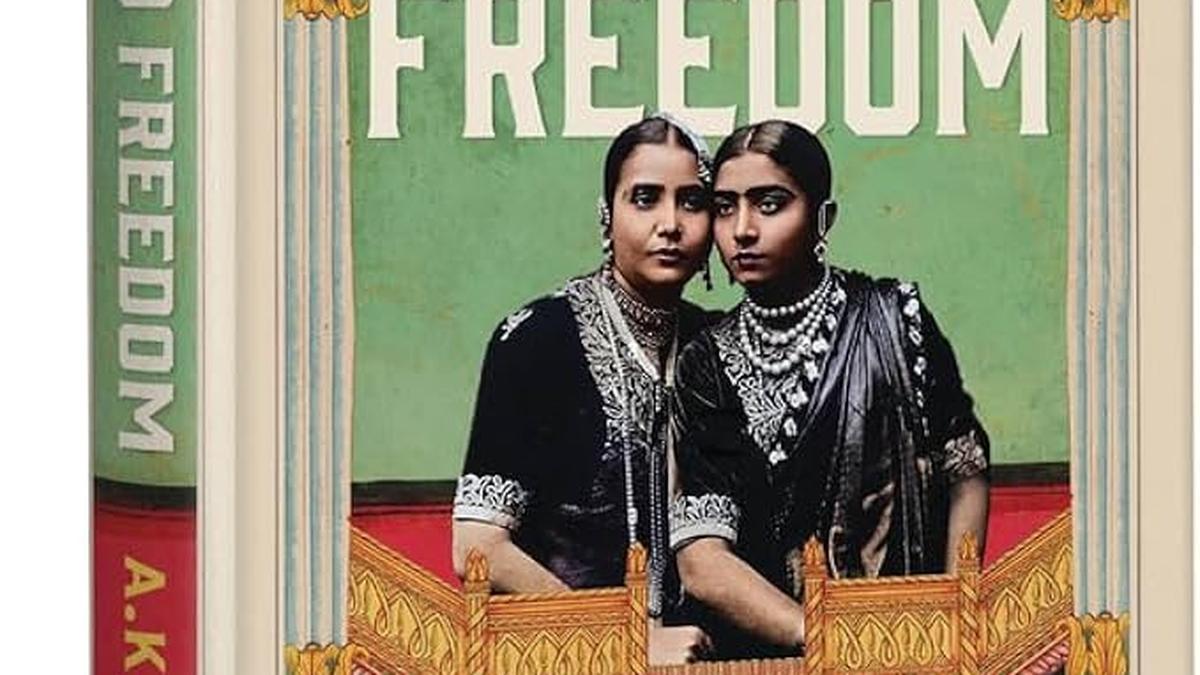

“When it comes to giving credit to women in whatever profession or movement, we can see a marked disinterest among historians,” writes historian A.K. Gandhi. The history of India’s freedom struggle, too, has been sifted and pruned; contributions of many, overlooked. In his book, Dance to Freedom, Gandhi pays tribute to one such lost community and their lost art: tawaifs, the forgotten heroines, and their journey “from luxury and influence to neglect and societal scorn”. Finding its roots in ancient Indian mythology and early dynasties — the Haryankas, the Guptas — the performative art rose to its peak in the medieval, Mughal years, and lost much of its muscle in British India. It is this rise and fall that Gandhi materialises in his latest book.

Following the lives of five courtesans, Gandhi writes a “soft history” of the position enjoyed by tawaifs before the advent of Europeans, as educated, noble, dignified women; how their policies and judgments impacted their position among the royals; and how tawaifs’ role in fighting the British was unrecognised, confined to nothing more than footnotes in Indian history. He interestingly separates the early British years in pre- and post-steamship periods. Steamships enabled British officials to bring their families to their respective stations, allowing European morals to reduce courtesans as “mere prostitutes who also sang and danced.” As the distinction dissolved, multiple “anti-nautch” movements arose, led by Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj, and joined by revolutionaries, demanding a shutdown of kothas. Mahatma Gandhi too called the profession “a social disease” and a “moral leprosy” that must be done away with.

The courtesans, however, had in them enough courage, grace and spirit to use their art as a tool for activism. Azizan Bai, born in the rich Lucknavi tradition of courtesans, operated in Kanpur circles as a spy. Often seen on the horseback, “in male attire decorated with medals, armed with a brace of pistols”, she fought till her last breath. Husna bai, the “Chaudharayan of Banaras”, confronted Mahatma Gandhi in a rally, organised the Kashi Tawaif Sabha, and took to singing the patriotic word. Begum Samru, the widow of mercenary Walter Reinhardt Sombre and ruler of Sardhana, was often called a sorceress or a witch by her enemies for her intelligent practical ways. She took keen interest in administration and in learning military techniques and displayed remarkable diplomatic skills. Begum Hazrat Mahal “rose from Pari to Begum” in the court of Mirza Wajid Ali Shah, the prince of Awadh (Oudh). When the docile and timid prince, inclined towards nothing but poetry, failed to save his province, Begum Hazrat stepped up and lead the protest and openly criticised the British who “felt no shame when it came to not keeping their word.” Dharman Bibi, left her newly born twins and sacrificed motherhood, to fulfill her duty towards her husband, Kunwar Singh, and the nation. Today, as Kunwar Singh is immortalised in history, there is hardly any mention of Dharman Bibi’s sacrifice. People in Arrah pretend not to know her, for the shame she might bring her royal patron; “so her memory has been swept under the carpet.” Gauhar Jaan, who popularised Hindustani classical music, also finds an honorary mention in Gandhi’s book.

History does them a disservice but the courtesans continue to live in legends and folklore. Despite the negligible space tawaifs occupy in history, there is no such dearth in popular discourse. Literature and cinema have done their due diligence: Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1972), Shyam Benegal’s Mandi (1983), Saba Dewan’s documentary (2009)The Other Song n or her book Tawaifnama (2019), Amritlal Nagar’s Ye Kothewalian (1959), Munshi Premchand’s Seva Sadan (1919), Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1993) and Manish Gaekwad’s much recent memoir of his mother’s life in the falling kothis of Bombay, The Last Courtesan (2023). Their struggles have been recognised by various art forms but their plight remains unheard.

Dance to Freedom’s timely release makes for an excellent companion piece to another cinematic tribute to tawaifs in pre-independence India: Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s OTT debut, Heeramandi, with its grand, hypnotic set up and ruthless, cunning and unforgiving characters, about which much has been written. The book provides necessary historical context to traditions such as nath-utrayi that the web-series portrays.

In the aftermath of World War II and at the peak of Quit India Movement, Heeramandi, its occupants and its visitors, stand at the cusp of the violent, immoral ways of the British and their duty towards their own people. Heeramandi represents tawaifs as a community and not as individuals who broke the barriers of gender to rise as revolutionaries. The five courtesans in A.K. Gandhi’s book are much luckier than the courtesans of the Bhansali universe, where relationships are fragile. Love does not triumph in the show, although glorified and much sought-after. Patrons are not as loyal as real-life Wajid Ali Shah and Kunwar Singh and the tawaifs are not immune to jealousy, greed or opioids. The nawabs have little power, except for some that is borrowed from their British masters, unlike the nawabs who are companions, and talented poets if not brave fighters, in the book.

When seen in the light of A.K. Gandhi’s book, the web-series shows tawaifs in possession of an affluence which they most likely lost by that time in history. It is commonly known (and amplified by Dance to Freedom) that as punishment for the courtesans’ rebellion in 1850s, the British confiscated their properties, relocated them, and levied heavy fines. They implemented stringent, biased laws (on marriage, adoption, etc.), rendering tawaifs powerless. The nawabs’ boycott of kothas followed this retaliation, making the courtesans lose their wealth and social stature. The show objectifies and sexualises them in the same misleading way that the British did; something A.K. Gandhi’s book spends 300 or so pages, debunking.