Where does ‘us versus them’ bias in the brain come from? Premium

The Hindu

Explore how implicit biases shape human societies, backed by psychology and neuroscience research, to understand intergroup dynamics better.

“All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others” — this line from George Orwell’s 1945 classic ‘Animal Farm’ perfectly describes how bias operates in human societies.

In a study published in May last year, psychologists explored how people subconsciously evaluate different racial groups. They screened responses from more than 60,000 participants belonging to four groups: ‘white’, ‘blacks’, ‘Hispanics’, and ‘Asians’ (67% of them lived in the U.S.)

Using a psychological test called an implicit association test (IAT), scientists found stark differences in participants’ explicit statements from their implicit beliefs. While everyone verbally said they believed in the equality of all races, they also harboured implicit biases in favour of socially advantaged groups. This bias was also universal, irrespective of the racial identity of the participants.

The IAT is built on the premise that if two things — words, concepts, events, etc. — have co-occurred in our experience over and over again, we put those two things together very quickly. The test includes a series of quick-fire rounds to sort words related to concepts (e.g. “thin”, “fat”, “white”, “black”, etc.) and assessments (“good” or “bad”) into categories. A participant’s score is based on the time taken to sort words when concepts and assessments are combined. For example, if test subjects combine “white” with “good” faster than they do “white” with “bad”, the test suggests they have an implicit bias favouring white people.

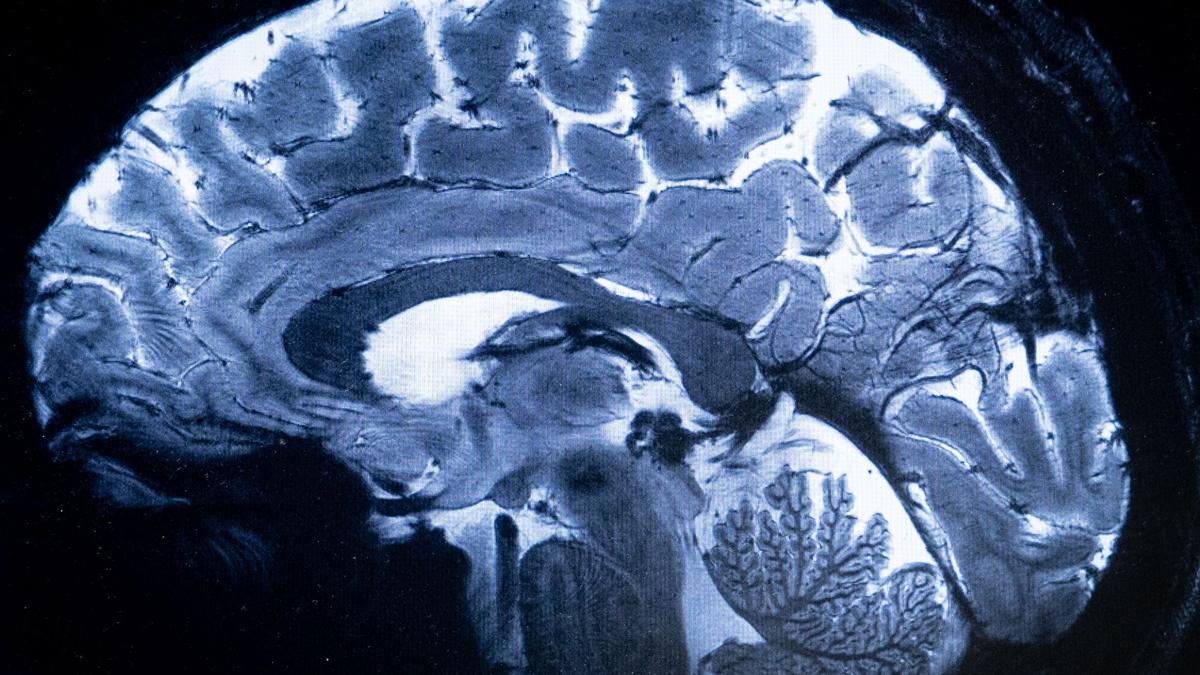

That all humans are equal is a scientific fact established by modern genetics. However, the history of humankind is replete with people from one cultural or social group treating those from others as if they are less than human — a phenomenon called pseudo-speciation. The basis of this deep-seated tendency in people continues to be the focus of intense research efforts in psychology and neuroscience.

Many recent studies have found that our brains process information about in-groups (i.e. “us”) and out-groups (“them”) differently. In particular, a study published on March 18, 2024, in Frontiers in Psychology reported that, bizarrely, the criteria our brains use to categorise others as “us” or “them” shift constantly. Researchers asked half of a group of young, white participants to describe how they — as white people — differed from black individuals. They asked the other half to describe how they differed from old persons. In this way, the researchers drew the participants’ attention to specific aspects of their own social identity (“white” or “young”) and to perceived differences from the respective outgroups.

Assessing the participant responses with IAT, the researchers found that directing participants’ attention to different facets of their in-group identity was sufficient to change their intergroup bias. That is, the participants’ preferences changed depending on whether their brains used age or race to classify others.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game