What citizenship laws do countries follow? Premium

The Hindu

What are the two principles followed around the world for granting citizenship? What is the law in India, and in the neighbourhood?

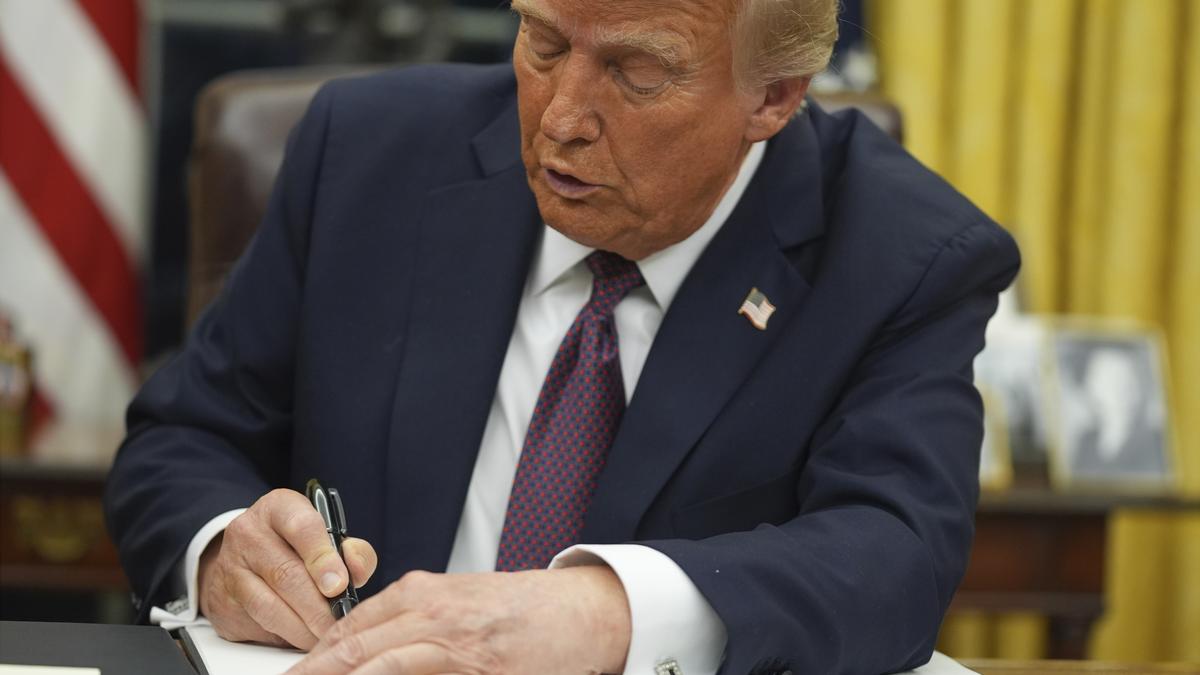

The story so far: In the gale of executive orders announced after Donald Trump assumed office for a second term, the President issued one diluting birthright citizenship, which has been written into the U.S. Constitution since 1866. The order has been challenged in court in more than 20 States and a federal judge has temporarily blocked it. If implemented, it will mean that children born to illegal immigrants — as well as those legally in the U.S. on temporary visas for study, work or tourism purposes — will not be eligible for automatic U.S. citizenship. At least one parent must now be a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident, the order says.

The 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was enacted in 1866, against the backdrop of the Civil War which had just ended, and was an effort to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to Black citizens. It was meant to overturn the infamous U.S. Supreme Court ruling of 1857 in Dred Scott vs Sandford, which held that enslaved people brought to the U.S. and their descendents could not be citizens of the country.

The principle was challenged in the 1890s, a time of rising anti-immigrant sentiment, when Wong Kim Ark, born in the U.S. as the son of Chinese nationals, went to visit relatives in China and was denied re-entry into the U.S. on the grounds that he was not an American citizen. In 1898, the Supreme Court upheld his citizenship, establishing that “every citizen or subject of another country, while domiciled here, is within the allegiance and the protection, and consequently subject to the jurisdiction, of the United States”. Over a century later, Mr. Trump is seeking to contest the court’s interpretation of “jurisdiction”, arguing in his executive order that the children of those “unlawfully present”, or whose residence in the U.S. is “lawful but temporary”, are not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. His supporters rail against the practice of birth tourism, or anchor babies, where foreign nationals seek to give birth in the U.S., in the hope that those babies will be able to help their families migrate to the country as well.

The U.S. follows the principle of jus soli (the right of soil), based on geography regardless of parental citizenship, as opposed to jus sanguinis (the right of blood), which gives citizenship based on the nationality of the child’s parents. According to the CIA’s World Factbook, there are only 37 countries which currently enforce the jus soli principle, of which 29 are in the Americas. Of the other eight, two are in India’s neighbourhood: Nepal and Pakistan, though the latter introduced a Bill seeking to end this.

Jus soli historically allowed colonisers to quickly outnumber native populations as citizens. “Countries that have traditionally built their national character through diverse immigrant populations have used jus soli as a way of integrating diversity into the common stream of nationhood,” says Amitabh Mattoo, dean of the School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, adding that countries protective of their culture and identity have generally followed the principle of jus sanguinis. Jus soli derives from English common law and, until anti-migrant backlash a few decades ago, was implemented in the U.K. and most of its former colonies, including India.

India offered automatic citizenship to all those born on Indian soil before 1987. Introducing the Citizenship Bill in Parliament in 1955, then-Home Minister Govind Ballabh Pant said, “The mere fact of birth in India invests with it the right of citizenship in India...we have taken a cosmopolitan view and it is in accordance with the spirit of the times, with the temper and atmosphere which we wish to promote in the civilised world.” Three decades later, sentiments had changed, in the wake of unrest in Assam due to increasing migration from Bangladesh as well as the influx of refugees from Sri Lanka, following the civil war there. “The time has come to tighten up our citizenship laws...We cannot be generous at the cost of our own people, at the cost of our own development,” said P. Chidambaram, Union Minister of State for Home Affairs, while introducing the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill in the Lok Sabha in 1986.

“America once considered itself a melting pot, welcoming immigrants to become citizens, but has lately abandoned that metaphor for the salad bowl of distinct ethnicities. The rise of identity politics as well as political Islam has led to this desire to redefine citizenship,” says Professor Mattoo. “It will certainly result in reduced immigration, both legal and illegal.”

The government’s announcement in the State Budget to set aside ₹300 crore for a Fund of Funds (FOF) and ₹100 crore for deep tech development has received praises from the industry leaders and experts who feel that these initiatives will go a long way in boosting the start-up ecosystem in clusters such as Mysuru, Mangaluru and Hubballi .

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game