The nightmare stories of Kafka and why they resonate

The Hindu

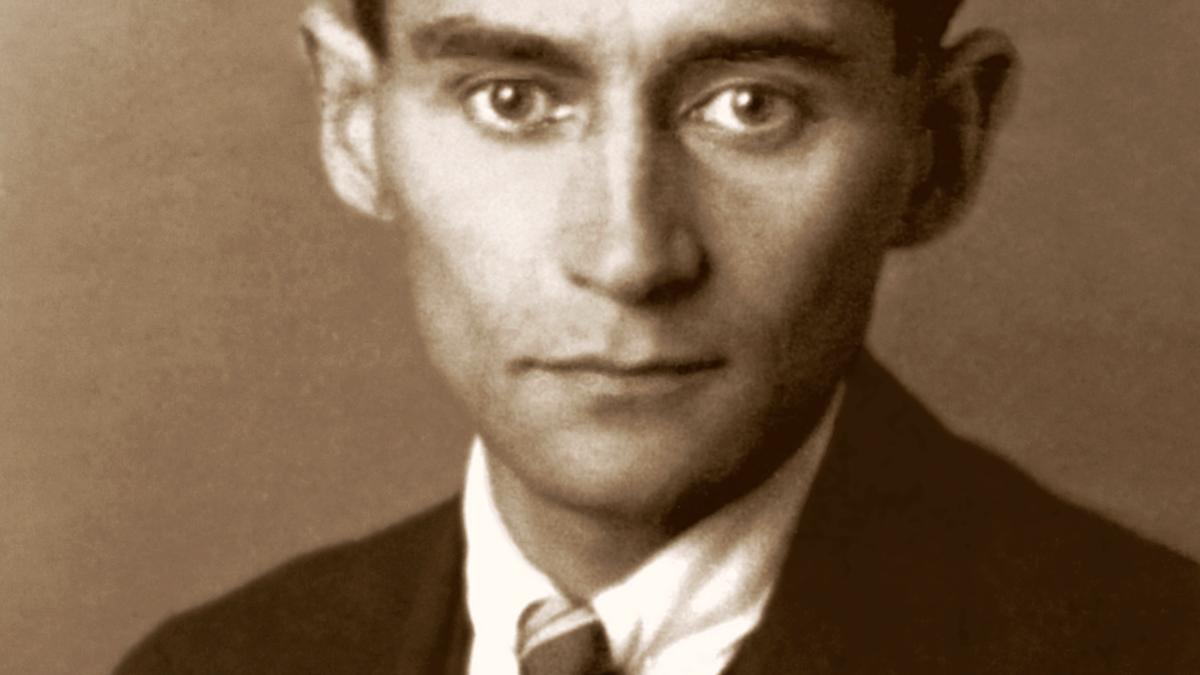

Celebrate Franz Kafka's centenary with readings, exhibitions, and new translations, exploring his enduring influence on literature

June 3, 2024 marks a centenary of the passing away of Franz Kafka, of tuberculosis at a sanatorium near Vienna, a day that will be marked with a reading of The Metamorphosis as part of the Oxford Kafka 2024 programme.

To celebrate Kafka’s legacy and enduring influence, an exhibition, ‘Kafka: Making of an Icon’, is also being held till October 27 at Weston Library, Oxford. A new generation of readers will get to see material from the Bodleian Libraries, which hold the majority of Kafka’s papers, like his notebooks, drawings, diaries, letters, and also original manuscripts of two of his unfinished novels, The Castle and America. Harvard University Press is out with a new translation of Kafka’s Selected Stories, edited and translated by Mark Herman.

Born in 1883, the son of a rich Czech merchant, Kafka studied literature and then took a degree in law, a profession he thought “would give him the greatest amount of free time for his writing”. He soon gave up working as a clerk to concentrate on his literary aspirations, always referring to his work as “scribblings”.

Though a few of his works were published during his lifetime, his major novels, The Trial, The Castle and America were published after his death, thanks to his editor, biographer and literary ambassador, Max Brod, who ignored his friend’s wish that all his papers be destroyed, and just before the Nazi occupation of Prague left for Israel with a suitcase containing Kafka’s manuscripts.

In his Epilogue to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of The Trial, Brod, writer, poet, journalist, playwright and commentator, mentions two notes found on Kafka’s writing table, addressed to him; one urges Brod to burn his papers unread, another says, “...this is my last will concerning all I have written: of all my writings, the only books that count are these: The Judgement, The Stoker, Metamorphosis, Penal Colony, Country Doctor, and the short story, Hunger Artists.” Brod explained he had good reasons to refuse to commit “the incendiary act”. In an essay, David Pryce-Jones writes that Brod rightly ignored Kafka’s wish, “on the grounds that Kafka was a life-enhancer and a longer life would have shown him how valuable his books were to others.”

Kafka’s nightmare stories, says Courtlandt Canby, have come to symbolise the helplessness of modern man, born into a world over which he has no control. In The Trial, for instance, Joseph K., a bank clerk is arrested, tried and executed for a crime of which he is unaware of. The first line of The Trial, begun in 1914 but published in 1925 posthumously, is now among the most-quoted, especially when the world seems complex and incomprehensible: “Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning.”

The warders won’t explain why he has been arrested, and the narrator is thinking aloud: “K. lived in a country with a legal constitution, there was universal peace, all the laws were in force; who dared seize him in his own dwelling?” The absurdity of Joseph K.’s situation is that nobody denies that the arrest defies logic — and yet people, his uncle and friends, offer him advice and help, and the lawyers go through with the process.