Study ups oft-smuggled Indian star tortoise’s conservation prospects Premium

The Hindu

Discover the beauty and plight of the Indian star tortoise, a vulnerable species facing illegal pet trade and genetic challenges.

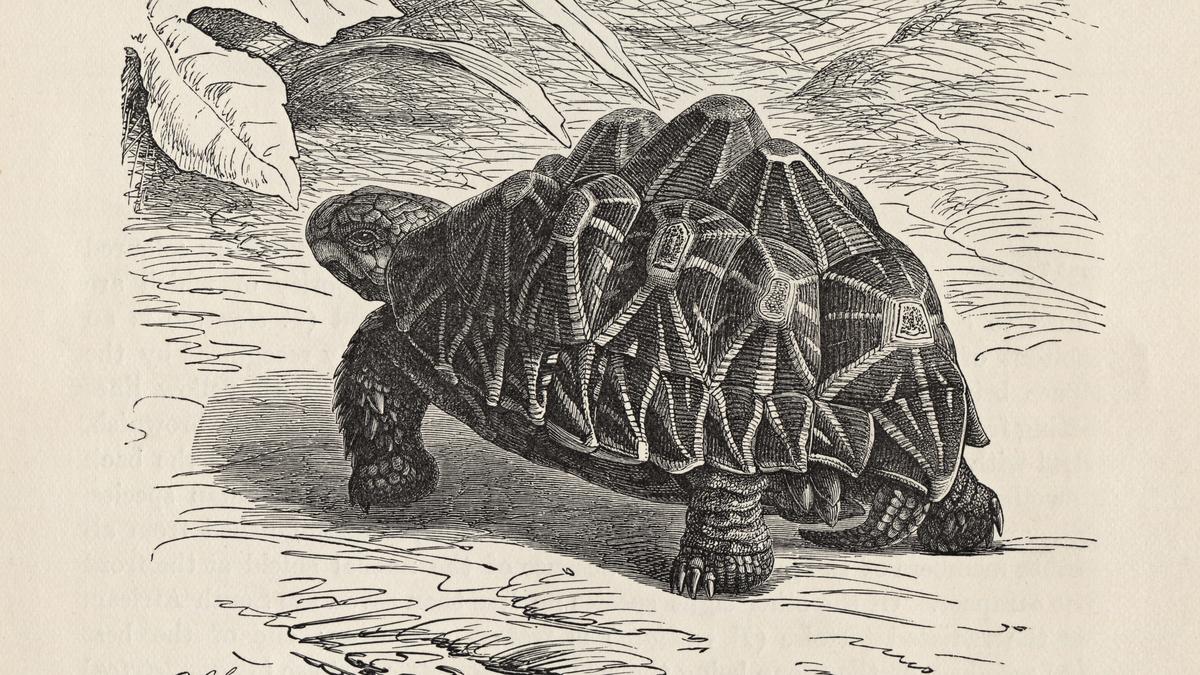

The Indian star tortoise (Geochelone elegans) is a sight to behold, with its obsidian shell and the striking Sun-yellow star patterns adorning it. These tortoises are hardy herbivores and are popular as exotic house pets — but they shouldn’t be. It’s illegal to own one in India but also unethical since they are vulnerable in the wild.

Endemic to the subcontinent, Indian star tortoises reside in arid pockets of northwest India (bordering Pakistan), South India, and Sri Lanka. However, members of the species have also been found in people’s homes as far afield as Canada and the U.S. The increasing demand for them as pets has entangled them in one of the largest global wildlife trafficking networks.

The Indian star tortoise is listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and in Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972, which provides the highest level of protection to animals in Indian law. Despite this, officials have already seized hundreds of tortoises being smuggled through the Chennai and Singapore airports and across the India-Bangladesh border this year.

Wildlife biologist Sneha Dharwadkar, cofounder of an NGO called Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of India, is worried unscientific releases of the seized tortoises could worsen their fate. “We can no longer simply take confiscated tortoises and release them in nearby forests,” Dharwadkar wrote in an email.

To find an alternative, researchers from the Wildlife Institute of India and Panjab University explored the diversity and natural distribution in India by sequencing the genomes of Indian star tortoise in zoos, wildlife reserves, and protected areas.

The study identified two genetically distinct groups of Indian star tortoises: northwestern and southern.

The genetic divergences showed up as differences in physical features that could inform strategies on where and how to release and conserve rescued tortoises, Subhasree Sahoo, a PhD student at the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, and first author of the study, said.