Saurashtra fossils say early humans didn’t stick to coast as they moved Premium

The Hindu

A new study of archeological sites in India’s Saurashtra peninsula, published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans in October, has mounted yet another challenge to the coastal dispersion model.

Genetic studies have painted a neat picture of human evolution and migration around the world. By studying how frequently DNA in the mitochondria (the cellular structure responsible for producing energy) mutates, scientists have found that Homo sapiens evolved in Africa for millennia, then emigrated to different parts of the world.

Scientists mostly agree on this out-of-Africa theory of human evolution and migration, but they frequently disagree on when exactly our ancestors migrated and what routes they took to different parts of the globe.

Several genetic studies have supported the coastal dispersion idea: that migrating humans travelled along the coast, especially in the tropics, where the weather was warm and wet and food was plentiful. In 2005, the mitochondrial genomes from 260 Orang Asli people revealed early humans dispersed rapidly around 65,000 years ago on the coast of the Indian Ocean before reaching Australia. In 2020, the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from the remains of a 2,700-year-old individual in Japan showed a strong “genetic affinity” with indigenous Taiwanese tribes. The authors of the study concluded the finding supported coastal migration. Human settlements in the Andaman archipelago have also been linked to coastal journeys.

But there’s a problem: archeological evidence has disagreed with the coastal dispersion model. For example, “all Palaeolithic archaeological sites in India are inland,” Michael Petraglia, director of the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution at Griffith University, said. Along with his team, Petraglia has studied several archeological sites in the country. “There is not a shred of archaeological evidence along the entire Indian Ocean coastline to support this model.”

Instead, Petraglia deferred to the inland dispersal model: the idea that human ancestors took “more interior, terrestrial routes”.

A new study of archeological sites in India’s Saurashtra peninsula, published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans in October, has mounted yet another challenge to the coastal dispersion model.

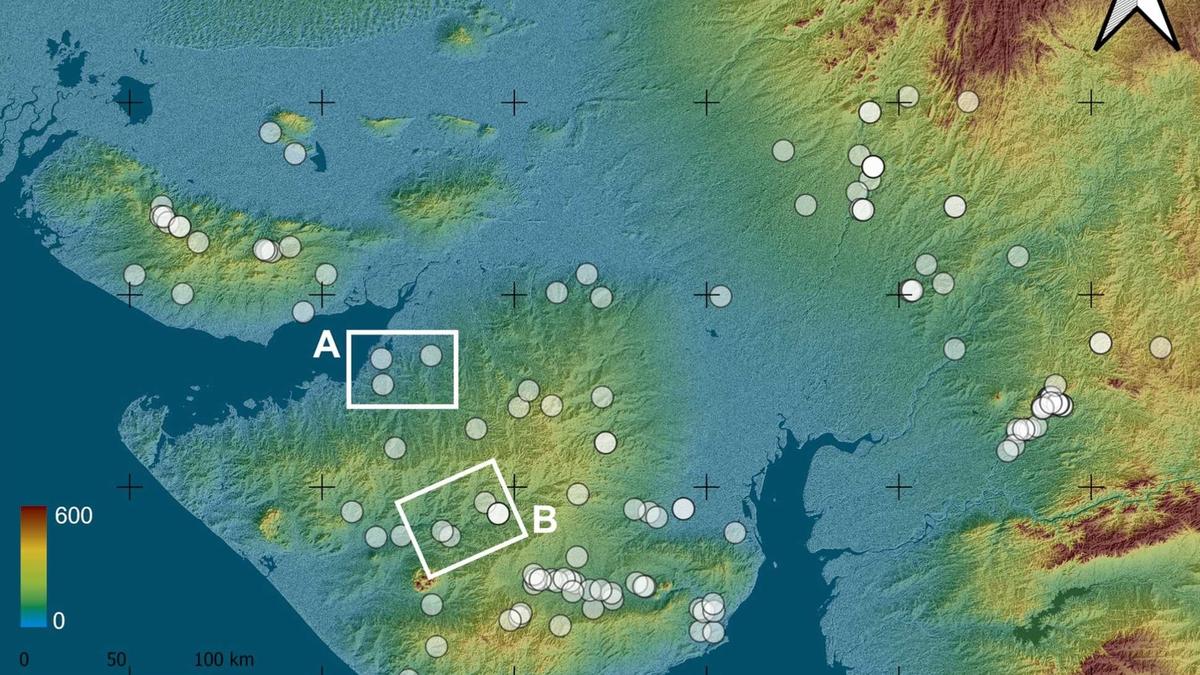

In the study, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology and the Tübingen University, Germany; the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara; and the University of Philippines investigated the Bhadar and Aji river basins of the Saurashtra peninsula in Gujarat. They discovered artefacts of tools made by early human inhabitants — pieces of chert, jasper, chalcedony, bloodstone, and agate that were chipped again and again to achieve a desired shape and size.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game