Review of Vandana Shiva’s Terra Viva — My Life in a Biodiversity of Movements: Clearing the air

The Hindu

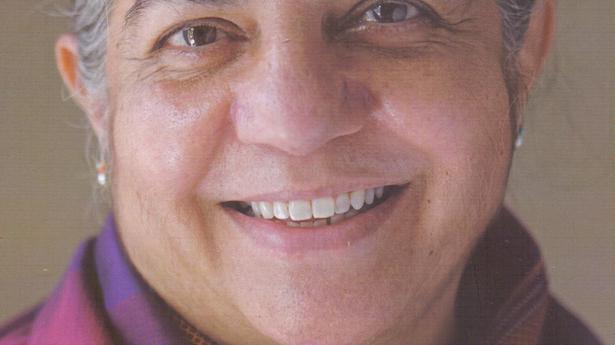

A child of the Chipko movement writes about the fascinating, brave, and often controversial, story of her life as a crusader to preserve the environment

For a couple of generations, certainly in India, and possibly even globally, the most persuasive image of social mobilisation for ecological causes was that of young women hugging trees in the Garhwal mountain range to protect them from being felled. That image of the Chipko movement remains seared in the collective consciousness and has been more than an image for many in these two generations, an inspiration; a spur for activism. Vandana Shiva, then a young physicist, metamorphosed into a sustainability warrior in that heady, memorable strike for conservation. In the mountains of Garhwal where she grew up in a liberal family environment, Shiva the eco feminist was hatched, as a child of the Chipko movement. And rightfully, this is where she begins the fascinating, brave, and often controversial story that has been her life in Terra Viva: My Life in a Biodiversity of Movements.

Shiva’s life and career, thanks to the prominence she has gained over the years, is nearly folk lore especially within the community that has taken the same path. Yet there are nuggets of information that only an autobiographic account is privy to, and she records them here. She does it before the book begins its rather breathless journey of towns and cities and countries she has stopped by, in her relentless quest to make the world see the power of natural resources, the need to conserve them, preserve seeds, and the ‘evil’ that multinational corporations and funding agencies do. From Peru to Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Ethiopia, South Africa, Tanzania, Ghana, Sri Lanka, or Indonesia and New Zealand, the book follows India’s homegrown warrior in her crusades across the world, recording meticulously the key elements of negotiations, hurdles and solidarity, achievements and setbacks that find her, or desert her.

The messages that the system that fuels a market economy is not really conducive for a survival economy that needs to be more diverse; or the irrational point of view that local use of a product does not create wealth, only commercial exploitation does that; or correcting the erroneous assumption that all forest ecosystems are ecologically equivalent; or even the rather contentious go-completely-organic advice, are reinforced nearly in every page. Shiva’s well known opposition to the World Bank’s schemes, the threat of homogenisation from seed MNCs, her principled opposition to the Green Revolution naturally find emphasis in the book.

That reckless exploitation of tropical forests during the colonial and post-colonial periods has cumulatively impacted and caused critical, nearly irreversible conditions of an eco disaster is another key message of the book, one, of course, anyone familiar with Shiva’s work will expect. The narration has clinical precision, and the conviction of a campaigner. Critics of her policies are as vocal as she is, particularly of her promotion of organic cultivation. Recently, harsh pronouncements targeted her, following Sri Lanka’s domestic crisis that was fuelled in part by the go-organic movement the government promoted over more conventional farming that ensured mass production.

But there is no question that her achievements are by no means trivial; and that her evangelical zeal cannot be ignored either. Working with communities, international climate activists and conservationists, she has marked tremendous successes. To quote a few, the Monsanto case at The Hague where ‘ecocide’ was recognised as a crime in international law; the 2009 Climate Manifesto; or the way in which Terra Madre or the slow food fair has taken off. These were long battles, stretching for years, and required the same zeal, energy and commitment, with which the movement was initiated, throughout the process. The war she launched, in collaboration with several others, on revoking the patent for Neem, for instance, took many years to fructify.

The significance of biodiversity, and the interconnectedness between species and life forms, cannot be overstated, particularly at a time when humanity is witnessing, on a daily basis, extreme weather events that leave a trail of disaster. It is clear that Shiva, once dismissed as a Cassandra by those unwilling to share her fears for the future, was right all along, after all.

However, after a point, the book seems like a listicle, items ticked off a bucket list, and one wishes that there were some more emotional insights and perspectives into what are undeniably larger than life movements in global environmental activism. While Shiva’s life is well chronicled, one can’t help yearn for more heart in the book, along with the energy and speed it has in abundance. The heart that might have spurred so many young women in the hills to bravely cling on to the trees as bulldozers, even husbands, stood in their path. For her path has been no less exciting or courageous, it cannot be too much to expect an insight into the emotions or internal conflicts that she might have faced. After all that is what one expects of autobiographies, to ride with the author through the ups and downs, their version of the rollercoaster, but along with them. Terra Viva does not really allow one to do that. Shiva informs her readers of crucial issues of global concern and demands action with an urgency that impresses, but she stops short of taking them along on the ride.