Review of Ramachandra Guha’s Speaking With Nature: Under the banyan tree

The Hindu

Review of Ramachandra Guha’s Speaking With Nature. The author profiles 10 people who he credits with laying the foundation of environmentalism in India.

Environmentalism isn’t just an idea; it’s also a verb. In his latest book, Speaking With Nature, historian Ramachandra Guha draws portraits of ten people who he credits with laying the foundation of environmentalism in India.

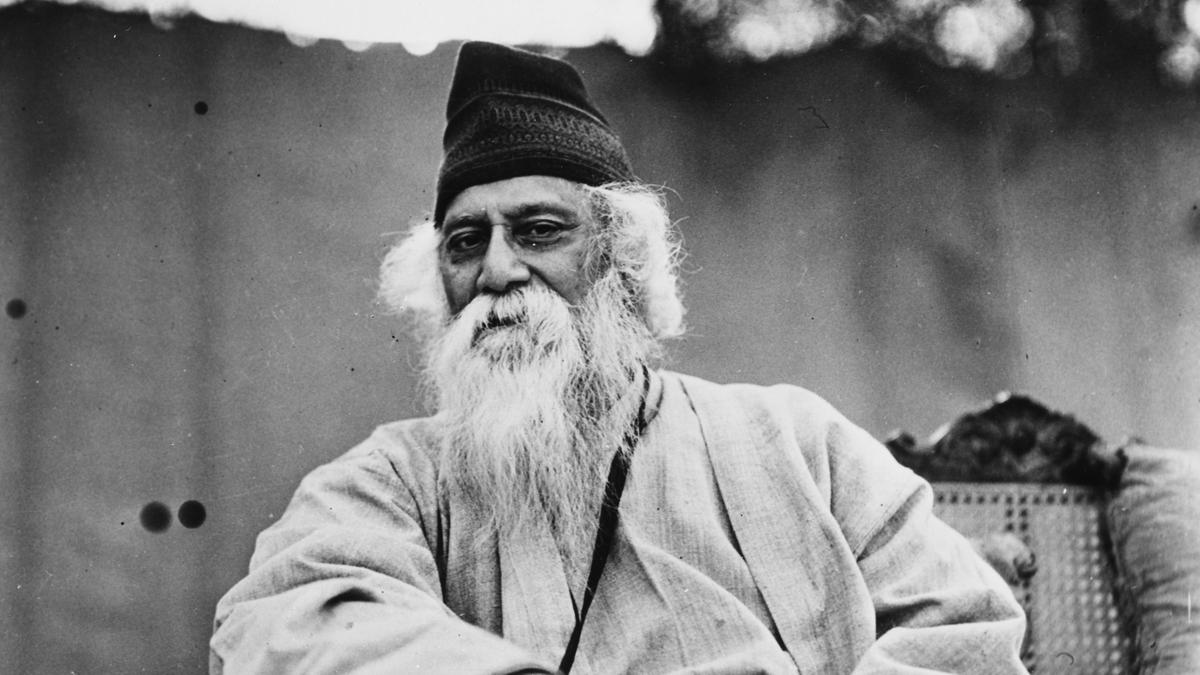

One would expect a list of tribal leaders, hunters-turned-conservationists, (‘repentant butchers’ as the author remarks in one section of the book), those who have spearheaded environmental movements, or professional conservationists and administrators. Guha though presents us with an unexpected selection of people — writer Rabindranath Tagore, sociologist Radhakamal Mukherjee, Hindutva thinker K.M. Munshi, the naturalist M. Krishnan, Gandhi follower Mira Behn, anthropologist Verrier Elwin and more.

Guha continues the questions he has asked in previous writings, in that he descries ‘full-stomach environmentalism’ — the Western idea that environmental consciousness can only come out of prosperity (suggesting that Indian thought cannot be environmental). The people he picks in this book, eight men and two women from all over the world, linked nature to broader social and political thought with reference to India. Another thing they had in common is that they wrote about their ideas, and were scholars. Refreshingly, the book leans on a variety of sources to piece together the ideas Guha puts forward. Readers may remember Jairam Ramesh’s tome on Indira Gandhi as an environmentalist (A Life in Nature); this book too uses letters, talks and papers as sources.

I read with great interest the chapter on Mira Behn, the sole woman in this book (the other lady is one-half of a married couple who advocated for ecological agriculture, Albert and Gabrielle Howard). Mira’s writings are especially interesting for two reasons. One is their relevance even today — one of her concerns was on the intrusion of pine trees in Himalayan oak forests, a problem which still persists (and is exacerbated by human-induced disturbance and fire); another was the disappearance of the Haldu tree, which still doesn’t get the ecological importance it deserves. The other is her enquiry into an unthinking forest department. In many passages, the book is not just an appraisal of the problems of India a century ago, but becomes a reflection of issues we face today.

Guha writes of Tagore describing cities as parasites, of anthropologist Elwin describing the Gond understanding of nature as both beautiful and savage, which is increasingly true under climate change.

On Tagore and Mukherjee, Guha recalls their fondness for a tree with “coils”, the banyan tree. Guha writes that Krishnan does not like Indian animals being called Western epithets (for example, the Gaur is wrongly known as the bison). Playfully though, Guha calls Krishnan India’s John Muir. Krishnan was a naturalist who wrote about all animals, whether big, small, endangered or common; and like Muir he too advocated for a view of untrammelled nature, Guha argues.

In its skilful framing of environmentalism not as an abstract or aesthetic concept but as something deeply linked to economics, agriculture and other fields of public interest, the book might be seen as a prophecy waiting to be fulfilled. We still require a much more ecological path to development, not crumbs off the table of industrial growth.

Among the very few societies the city still has, Suchitra Film Society in Banashankari stands out as the city’s pioneer. Founded in 1971, it has a legacy spanning over 50 years. During a time when access to international and independent cinema was limited, Suchitra introduced people of Bengaluru to world cinema, rare classics, and art films, building a community of passionate film lovers. This society helped shape the city’s film culture, providing a space where cinema could be discussed, celebrated, and appreciated beyond mainstream trends. Today, however, Suchitra and other film societies like it are struggling to survive in a world transformed by digital entertainment.