Review of Ismail Kadare’s ‘A Dictator Calls’, translated by John Hodgson and longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024

The Hindu

A Dictator Calls by Ismail Kadare explores the parallels between tyrants and fiction writers in a gripping narrative, longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024

For the uninitiated, a tyrant first learns to master storytelling. Fiction, really, is their thing. Otherwise, how else would they inspire purchase? Their ability to present a larger-than-life, unquestionable, god-like figure is directly proportional to the finesse with which they narrate an agenda-driven yet mesmerising story effectively and repeatedly until it achieves the status of the truth.

How then is a tyrant any different from a fiction writer? In the face of tumultuous events, if an artist chooses to remain silent, exhibiting the characteristic insecurity and cowardice that tyrants display, then aren’t they the same? The comparison appears outrageous. But it’s one of the major themes of the 2024 International Booker Prize-longlisted novel, A Dictator Calls: The Mystery of the Stalin-Pasternak Telephone Call.

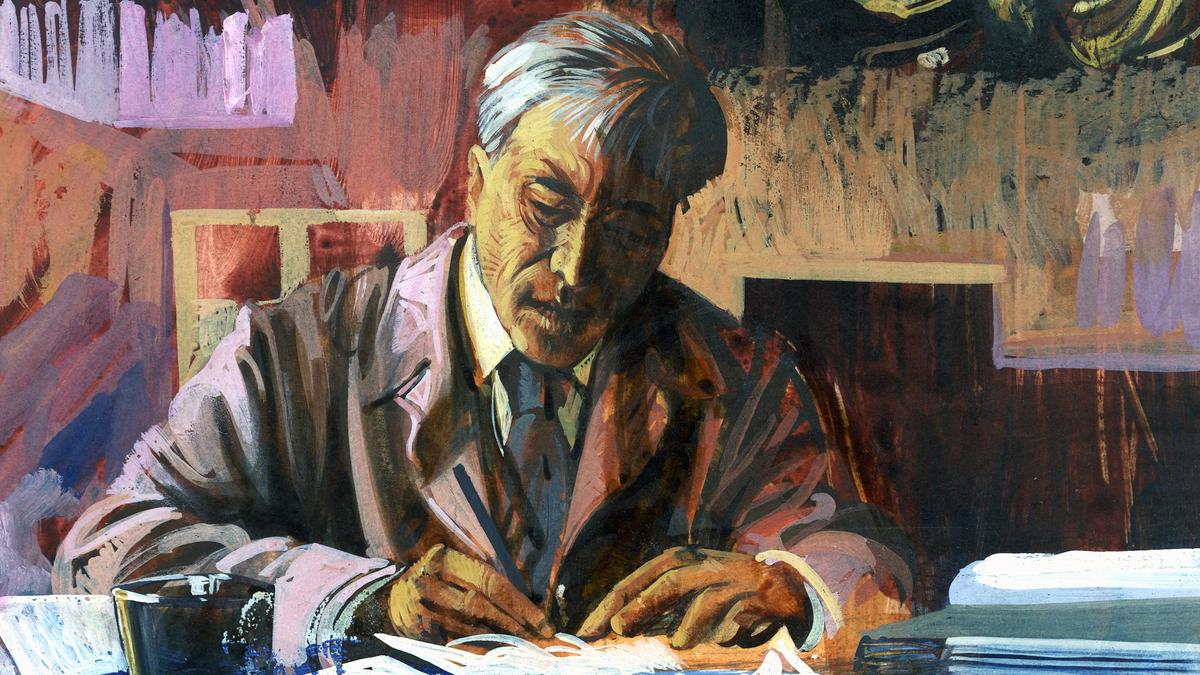

Written by Ismail Kadare, the inaugural winner of the Man Booker International Prize (2005), and exquisitely translated from the Albanian by his long-time collaborator John Hodgson, A Dictator Calls hyperfocuses and minutely analyses the 13 versions of a three-minute telephonic conversation between Joseph Stalin and Nobel Prize-winning poet Boris Pasternak on June 23, 1934, beginning with the text from the KGB archives first.

The timeline is important here. As is the case with every authoritarian ruler who goes berserk when they find power slipping from their hands. The 1930s was such a time for Stalin. If the rise of civil and political unrest wasn’t enough, being mocked by a poet —Osip Mandelstam — added insult to injury. Mandelstam wrote and performed a satirical poem, ‘Kremlin Highlander’, in 1933, amidst a circle of literary figures, including Pasternak and Anna Akhmatova. He was exiled for this act.

Kadare writes in the book: “As he testified later, Pasternak had not waited for the end before interrupting the author [Mandelstam], ‘Forget you ever read me that… verse. That’s not art, it’s suicide. I’m not getting involved with it.’” He notes this not to humanise Pasternak, but to expose the fallible nature of artists, who much like dictators are terribly anxious creatures. Sample this: Stalin calls Pasternak to ask him his opinion of Mandelstam. Upon receiving a cowardly response, the dictator tells him that he could’ve defended his friend better and hangs up. Pasternak tries to connect with Stalin again but in vain.

Their conversation haunts Pasternak throughout his life. Kadare submits: “The particular thing here was that both sides, the state and the writer, were equally deplorable.” After establishing this fact, Kadare goes deep into exploring the relationship between a writer’s role in a dictatorship and the way the phenomenon of gossip and curiosity continuously makes and unmakes this writer’s (Pasternak’s) image as ‘one of the greats’.

Interestingly, the novel begins with a writer protagonist, much like Kadare, who had studied in the Albanian capital of Tirana and at the Gorky Institute, Moscow, deliberating on those three minutes in Pasternak’s life because “[they] belonged to the same family, that of writers”. Very meta. This literary device helps reduce the distance between the novelist and the writer-protagonist, which is further put to test when, much like what Kadare does in A Dictator Calls, the protagonist writes a novel “about memory”, which according to him, “was perfect, finished, which meant both beautiful and at the same time dead”.

NDA government in A.P. neglecting students and education sector badly hit, alleges Jagan Mohan Reddy

YSR Congress Party (YSRCP) president Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy has criticised the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in Andhra Pradesh, accusing it of neglecting all sectors and not paying the fee reimbursement benefits to the students.