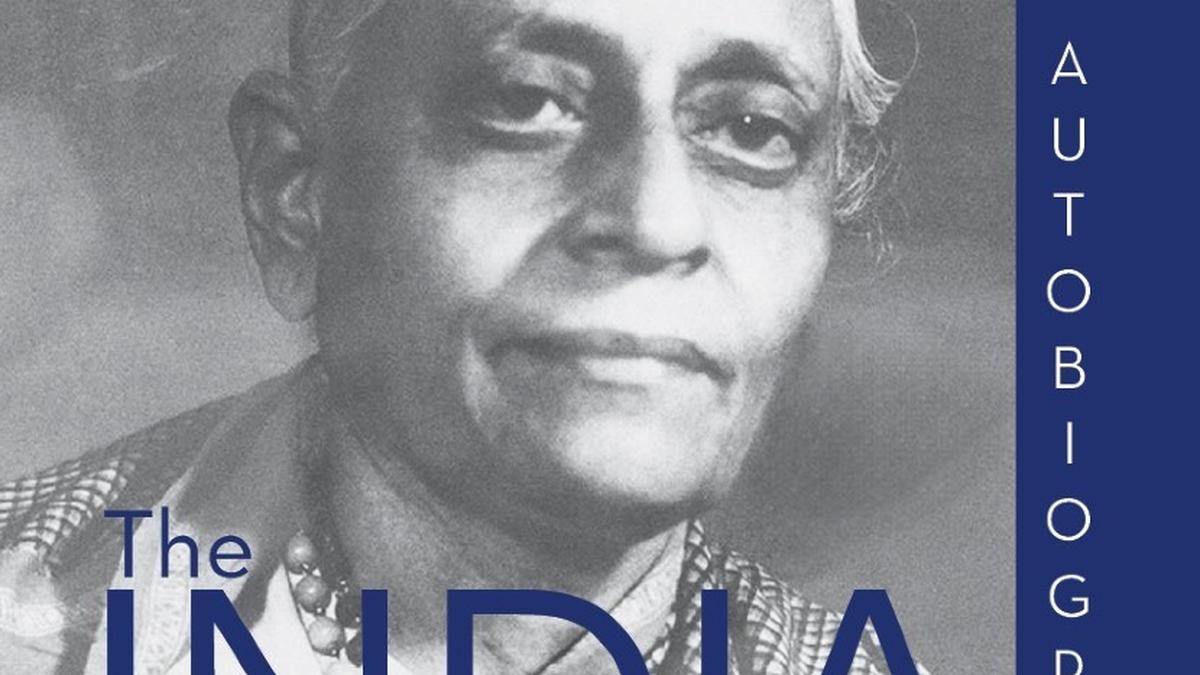

Portrait of a woman, social worker, Gandhian, and patriot from Madras

The Hindu

The biography of patriot S. Ambujammal, translated into English as "The India I Saw," reveals her fascinating life journey.

For a part of last year, I worked on translating Naan Kanda Bharatham, the biography of the patriot S. Ambujammal (1899-1981). The book had long been a favourite of mine, for I found her life fascinating and the simplicity and honesty of her narrative an absolute delight. When Mini Krishnan, the noted editor, asked me for ideas, it was therefore with alacrity that I suggested it as a suitable work for translating into English. Thanks to Mini, the book, The India I Saw, was published by Rupa Publications, with support from the Tamil Nadu Textbook and Educational Services Corporation. It is available for purchase in bookshops and online, and proceeds from the sale go to the Srinivasa Gandhi Nilayam (SGN), the social service organisation that Ambujammal founded in 1948.

Her life is one of many layers. At the core, there is Ambujammal, belonging to high profile lineage of Iyengars on both sides, her mother being a daughter of Sir V. Bhashyam Iyengar and her father Sriman Srinivasa Iyengar, a legal luminary. There was wealth, power, and social prestige. And yet melancholy brooded over the 150-ground Amjad Baugh on Luz Church Road where the family lived. Ambujammal, being a girl child and sickly at that, was considered unwanted, while her younger brother Parthasarathy received all the attention. The arranged marriage to Desikachari from Kumbakonam, who was forced to relocate to the city and live with his in-laws, was not a success. Their only child drifted while Desikachari himself suffered a breakdown and had to be sequestered for much of his life. A high-flying father who was a tyrant at home and a sickly mother did not help. Brother had his share of great troubles, and it was the arrival of Mahatma Gandhi and Kasturba in Madras in 1915 that proved a turning point in Ambujammal’s life.

Father became a great supporter of Gandhi, though they would later fall out over the latter’s treatment of Bose. To Ambujammal, Gandhi was the guiding light. He encouraged her to discover herself, a journey that led her into the freedom struggle. Her horizon broadened — sheltered existence gave way to interaction with men and women from various strata of society. She picketed shops, organised protests with gusto, and served a term in prison as well. The book names several freedom fighters of whom we sadly know next to nothing today. Somewhere along the way, she defied her father in a Gandhian way.

An interesting sidelight is the proficiency she acquired in Hindi, translating many stories of noted Hindi writers into Tamil. One among these, of Munshi Premchand, was serialised in Ananda Vikatan and became M.S. Subbulakshmi’s debut film Seva Sadanam. At the Mahatma’s behest, she translated the Tulsi Ramayana into Tamil. But it was to social service that she was increasingly drawn, and so following Gandhi’s assassination, she established the SGN, in memory of her biological and spiritual fathers, for the uplift of women. It continues to do what she envisaged, in a quiet way. The Tulasi holder at the entrance has buried deep within it a small urn containing ashes from Gandhi’s pyre.

Ambujammal served as the chairperson of the Madras Social Welfare Board after Independence, and it was also under her leadership that the Avadi Congress of 1955 took place. The street in Alwarpet where she resided and where the SGN functions from is named after her and the neighbouring one after her father. It is telling that she who was unwanted at birth is the one enduring celebrity of the Bhashyam Iyengar-Sriman Srinivasa Iyengar clans.

(V. Sriram is a writer and historian.)

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game