Overcoming the Aryan-Dravidian divide

The Hindu

Many eminent scholars, both local and international, have written about the Dravidian movement’s colonial origins

The Governor of Tamil Nadu has been criticised by some for expressing his views on the Aryan-Dravidian divide. Some have gone to the extent of calling this political interference. This is unfair. Expressing one’s views on a sensitive issue cannot be construed as political interference.

What the Governor has done through his comment, however, is disturb the popular view that former Tamil Nadu Chief Minister C.N. Annadurai’s forsaking of the demand for a separate Dravidian state was only a practical compromise, and that Aryans and Dravidians continue to remain racially different people. The eminent historian, P.T. Srinivasa Iyengar, never subscribed to this view, even though he maintained that cultural differences existed between the Vedic and non-Vedic people. In Pre-Aryan Tamil Culture, he wrote, “A careful study of the Vedas… reveals the fact that Vedic culture is so redolent of the Indian soil and of the Indian atmosphere that the idea of the non-Indian origin of that culture is absurd.”

The Governor called the Aryan-Dravidian divide a handiwork of the British, which has been criticised as toeing the Hindutva line on the issue. This criticism is also unfair because many eminent scholars, both local and international, have written about the Dravidian movement’s colonial origins. The linguistic theory, unscientific histories of racial origins, the politics of the non-Brahmin movement and the modern rationalism of the self-respect movement all have deep roots in colonial thought.

One of the key early proponents of the idea of Dravidian language family as a scientific entity was Robert Caldwell, in 1856. Many may not know that 40 years before Caldwell, Francis Whyte Ellis, the Collector of Madras, had already laid the foundation for Caldwell’s theories through his writings. The American historian Thomas Trautmann writes, “Ellis’s Dravidian proof is a dissertation... [in which] we see more clearly the relation between the languages-and-nations project and the properly Orientalist scholarship of the British in India.” This “languages-and-nations project”, or tendency to link languages to nations, is, according to Trautmann, “not a matter of pure science freeing itself from the shackles of religion, as it has often been represented…[but] its deep roots are in the Bible, in the genealogy of the nations that descended from Noah and his three sons.” Even more problematic is the languages-and-race project. Trautmann says about this, “European view of race as a fundamental force of history had a deep effect on the interpretation of Indian history, and what I have called the racial theory of Indian civilization… how much text torturing is necessary to sustain the idea of the encounter of Indo-European and Dravidian languages in India as racial in character, and how false is its racially essentializing identification of civilization with whiteness and savagery with dark complexion.”

How far politics has overtaken science and history is clear from the fact the one can hardly find mainstream criticism of Caldwell’s philology today. Just a decade after Caldwell’s work was published, Charles E. Grover of the Royal Asiatic Society wrote in his famous work on Tamil folk songs, “[about] the true character of the language and linguistic progress made since the publication of Dr. Caldwell’s book, it may be noted that the learned Doctor gives an appendix containing a considerable number of Dravidian words which he asserts to be Scythian… It is now known that every word in this list is distinctly Aryan.”

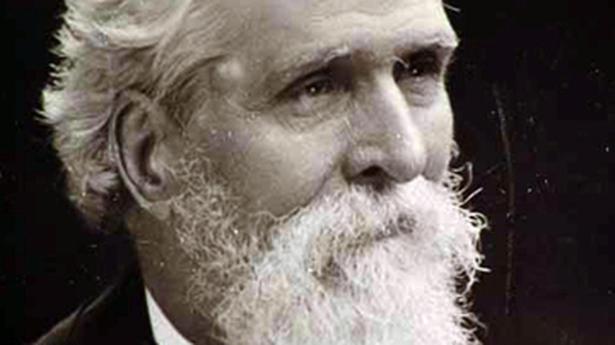

It was works of missionaries like Caldwell and G.U. Pope that British authorities exploited for political needs. As Director of The Hindu Publishing Group, N. Ram notes in a paper in the Economic and Political Weekly in 1979, influenced by these works, “the brutally repressive Governor”, Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant-Duff, looked at the non-Brahmins during his 1868 address to the graduates of the University of Madras and said, “you are of pure Dravidian race” and “I should like to see the pre-Sanskrit element amongst you asserting itself more”.

The eminent Cambridge historian, David Washbrook, identified the roots of Dravidian or non-Brahmin politics not in historic fault lines that were supposedly plaguing Tamil society but in “the novel types of government and politics which developed under the British in the early years of the present century.” According to Washbrook, it was the centralisation of bureaucracy in late 19th century Madras that led to fear among British civilians of “caste cliques” which could now control not only the districts but the entire province. So, the policy had to be ‘divide and rule’. That important leaders of the non-Brahmin movement were influenced either by colonial inheritance or narrow interests is best illustrated by Rajmohan Gandhi’s description of one of its founders, T.M. Nair, “entering politics as a congressman…holding brahmins responsible for an electoral reverse… he left the congress and became one of SILF’s founders… always found in western attire, a practice yet to spread among south Indian men. In a series of articles…he argued that British authority had kept India united” and “tried to convince Montagu that the Home Rule league was financed by German money.”

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game