One person, one vote, one value Premium

The Hindu

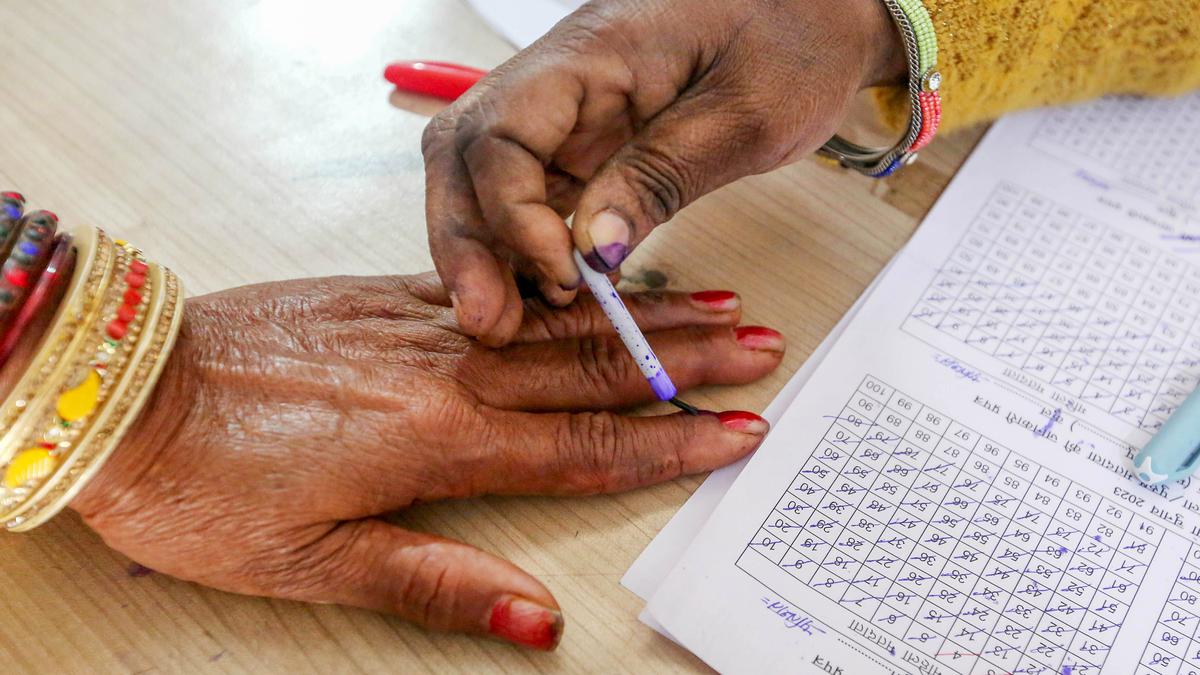

Along with addressing quantitative dilution of vote value, the next Delimitation Commission needs to address qualitative dilution so that minorities are represented more adequately

Political equality in liberal democracies is not only about equality of opportunity to participate in the political decision-making process, but also about carrying a vote value that is equal to that of other members of the community. According to the legal scholar Pamela S. Karlan, the right to vote can be diluted quantitatively and qualitatively by redrawing the boundaries of the constituency in an electoral system. Quantitative dilution happens when votes receive unequal weight due to huge deviations in the population among the constituencies. Qualitative dilution happens when a voter’s chance of electing a representative of their choice is reduced due to gerrymandering (redrawing of boundaries to favour a candidate/party). Thus, delimitation of constituencies plays a major role in strengthening or weakening democracy.

To avoid these dilutions, our Constitution framers envisaged appropriate safeguards to ensure equal political rights for all citizens. Articles 81 and 170 of Constitution state that the ratio of the population for the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assembly constituencies shall be the same as far as practicable. Article 327 empowers Parliament to make laws related to the delimitation of constituencies, which cannot be questioned in a court of law. Based on this, the government forms an independent delimitation commission headed by a retired Supreme Court judge to avoid qualitative dilution. Articles 330 and 332 guarantee reservation of seats for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in Parliament and State Legislative Assemblies, which need to be kept in mind during delimitation. Delimitation of constituencies needs to be carried out regularly based on the decennial Census to maintain equality of the vote value as far as practicable.

The government has constituted four delimitation commissions so far: in 1952, 1962, 1972 and 2002. The first delimitation order in 1956 identified 86 constituencies as two-member constituencies, which was abolished by the Two Member Constituencies (Abolition) Act, 1961. The second delimitation order in 1967 increased the number of Lok Sabha seats from 494 to 522 and State Assembly seats from 3,102 to 3,563. The third delimitation order of 1976 increased the number of Lok Sabha and State Assembly constituencies to 543 and 3,997, respectively. Due to the fear of more imbalance of representation, the 42nd Amendment Act in 1976 froze the population figure of the 1971 Census for delimitation until after the 2001 Census. The Delimitation Act of 2002 did not give power to the Delimitation Commission to increase the number of seats, but said that the boundaries within the existing constituencies should be readjusted. The Commission allowed up to 10% variation in the parity principle; yet around 17 parliamentary constituencies and many more Assembly constituencies violated this so that each representative could represent more people. But the fourth Delimitation Commission was able to reassign reserved constituencies, which increased the number of seats for SCs from 79 to 84 and STs from 41 to 47 based on the increase in population. The moratorium was extended until the first Census after 2026 for any further increase in the number of seats.

The population of Rajasthan, Haryana, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Gujarat has increased by more than 125% between 1971 and 2011, whereas the population of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Odisha has increased by less than 100% due to stricter population control measures. This also reveals a huge variation in the value of vote for a people between States. For example, in U.P., an MP on average represents around 2.53 million people, whereas in Tamil Nadu, an MP represents on average around 1.84 million people, a quantitative dilution.

The qualitative dilution of vote value parity can be used as a tool to sideline or make insignificant the votes of minorities. This can happen in three ways. The first is cracking, where areas dominated by minorities are divided into different constituencies. The second is stacking, where the minority population is submerged within constituencies where others are the majority. And the third is packing, where minorities are packed within a few constituencies; their strength is weakened everywhere else.

The qualitative dilution of vote value was highlighted in the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution and the Sachar Committee Report: in a majority of the seats reserved for SCs by the Delimitation Commission (1972-76), the population of Muslims was more than 50% and also higher than the SC population. And constituencies which had a large SC population and a lower Muslim population were declared unreserved. This has a major impact on the number of Muslim representatives in Parliament. At present, the share of Muslims MPs in Parliament is only around 4.42%, whereas the Muslim population is 14.2%.

Delimitation cannot be postponed further as it will lead to more deviation in the population-representation ratio. At the same time, the interests of the southern States have to be protected as their representation in Parliament might weaken due to more seats being assigned to States with a higher population growth. Along with addressing quantitative dilution of vote value, the next Delimitation Commission needs to address qualitative dilution so that minorities are represented more adequately.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game