On the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna | Explained

The Hindu

India's outreach to Sri Lanka's JVP leader sparks speculation ahead of elections, signaling a shift in relations.

The story so far: On February 5, an unlikely visitor landed in Delhi from Sri Lanka on an official invitation. Anura Kumara Dissanayake, the leader of the National People’s Power (NPP) alliance, received a red carpet welcome, following which two top officials spent time with him in the capital. The main constituent of the NPP is the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), and Mr. Dissanayake is its leader. The Indian outreach to the JVP has set off much speculation in Sri Lanka. The country is to go through a presidential election this year followed by parliamentary elections this year or the next. A survey conducted by the Health Policy Institute showed that 50% of respondents favoured Mr. Dissanayake as the next President. Since its inception, the party has had a bad history with India. But Mr. Dissanayake’s meetings with National Security Adviser A. K. Doval and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar have created new optics in the run-up to the election.

Over its five decade-existence, the JVP, which calls itself Marxist, but has been mostly a Sinhala nationalist party, has viewed India as an expansionist power seeking to colonise Sri Lanka.

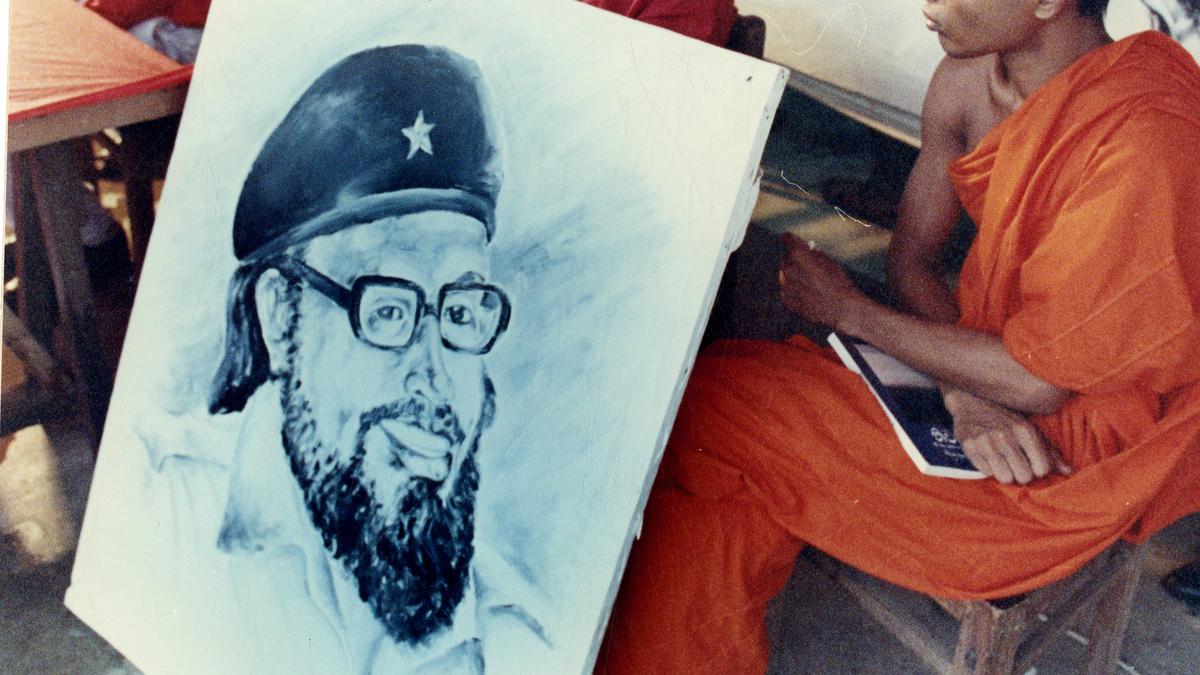

The JVP was formed in 1965. Its founder Rohana Wijeweera, who came from a family of modest means in coastal southern Sri Lanka, already had exposure to leftist ideologies through the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, before he went as a student to Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba International University, where he mingled with leftists from all over the world. On his return, he aligned himself with the Ceylon Communist Party (Maoist), before breaking away to form the JVP, with the intention of creating a revolution to turn Sri Lanka into a socialist state. Its members were mostly the youth who were unable to find jobs in the Sri Lankan economy, comprising British-era trading houses manned by Colombo’s English-speaking elites.

The cadres of JVP imbibed the party ideology from lectures known as the Five Classes — on the crisis of the capitalist system in Sri Lanka; history of Sri Lanka’s left movement; history of socialist revolutions; Indian expansionism; and the path of revolution in Sri Lanka. However, within no time, JVP found it more expedient to push class struggle to the back-burner, and became a vehicle for majoritarian Sinhala-Buddhist sentiments.

In the 1970 election, the JVP campaigned for Sirima Bandaranaike’s leftist United Front coalition comprising of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the Lanka Sama Samaja Party and the Communist Party. But the JVP’s support for Sri Lanka’s ‘bourgeois’ left was short-lived. In April 1971, it carried out an armed insurrection. The plan was to take over police stations first. The government, despite receiving prior intelligence, was caught unprepared. A state of Emergency was declared and Wijeweera was jailed. But the Sri Lankan tri-services were a ceremonial force and the government had to appeal to foreign nations for help. The Indian Army, Navy and Air Force played a part in thwarting the rebellion. The insurrection was overcome after a few weeks and some 15,000 JVP cadres were arrested. The death toll was over a 1,000, including civilians, police personnel and Sri Lankan armed forces personnel.

In 1977, with the election of J. R. Jayewardene, who went on to politically dominate the country for a decade, the Sri Lankan economy changed full tilt from the Bandarnaike era of socialist nationalisation, to liberalisation and the entry of free market forces. Jayewardene also released all JVP prisoners including Wijeweera, who went on to contest the 1982 presidential election, polling 4% of the vote. Some make the case that Jayewardene used the JVP to weaken the SLFP and the “old left”. Indeed, the JVP made SLFP’s Sinhala Buddhist plank its own from about the time of the 1983 anti-Tamil riots and the flaring up of the Sinhala-Tamil ethnic conflict.

Delhi’s growing involvement in the conflict led to anti-India sentiment among the Sinhalese majority. In June 1987, the Indian Air Force carried out Operation Poomalai to airdrop food to the north of Sri Lanka, which was Tamil-dominated, at a time when Sri Lankan forces had laid siege to the province, believing that they had cornered the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and its leader Velupillai Prabhakaran. The next month came the India-Sri Lanka Accord under which Sri Lanka introduced an amendment in its Constitution to devolve political power to the Tamil north and east. However, the LTTE rejected the Accord, and the soldiers that India sent under the banner of the Indian Peace Keeping Force to disarm the LTTE, soon found themselves in a war against the group.

U.S. President Donald Trump threatens 200% tariff on wine, champagne from France, other EU countries

Trump threatens 200% tariffs on European alcohol in response to EU levies, sparking trade tensions and market uncertainty.