Musi Development project in Telangana: Riverfront dream with a human cost

The Hindu

Shaikh Mujahid laments the demolition of homes along the Musi River for a development project in Hyderabad.

Shaikh Mujahid’s melancholic gaze ricochets off the walls of the closely built tenements before settling on the floor, littered with red bricks and cardboard. “This was where my grandchildren used to play,” he says, his voice heavy as he gestures towards the verandah now buried under rubble.

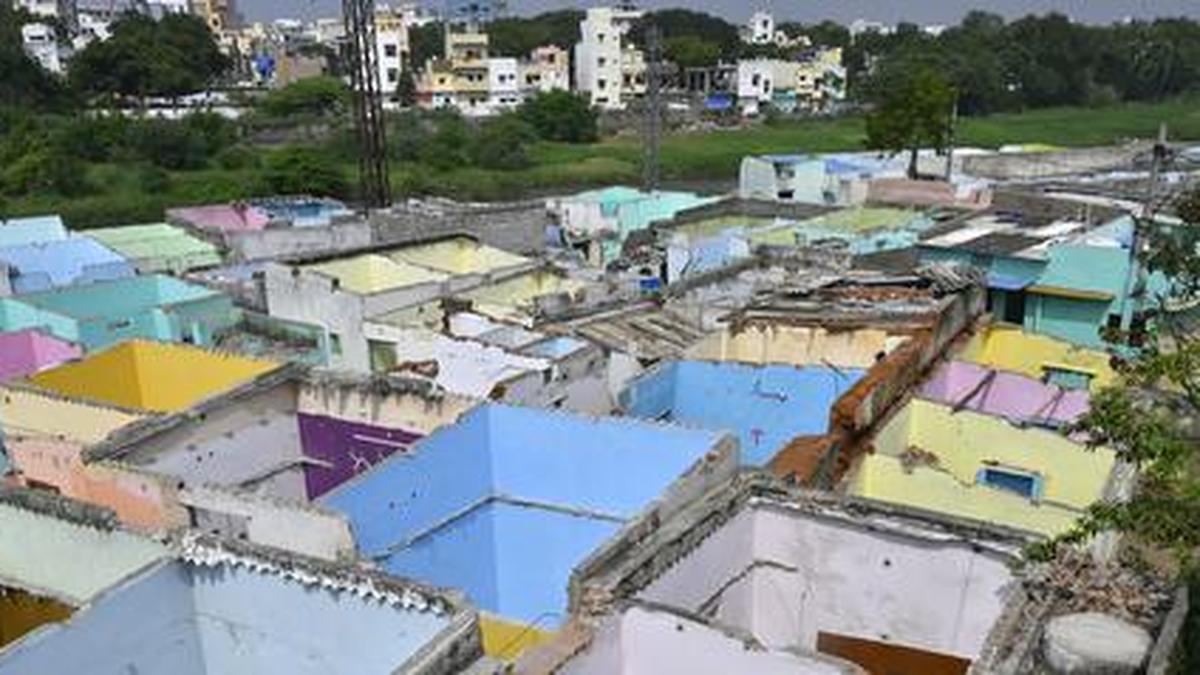

In his late 50s now, Mujahid once shared this home — a modest structure on 156-square-yard plot divided into small units of two rooms, a kitchen, and a toilet each — with his three sons, a daughter and their families. Located in Shankar Nagar, a slum in Hyderabad’s Chaderghat area, the house was built 12 years ago with the combined savings of his four children. Barely 30 feet away, the shrinking Musi River snakes through the 435-year-old city.

Mujahid had acquired the plot from Nirmal Singh, a member of the Kachi community who, like many others, was gifted land on the Musi riverbed by the Asaf Jahi kings to grow fodder and vegetables. “They tore the house down despite pleas. Now, my children are scattered,” Mujahid laments.

On October 1 this year, scores of hired labourers, allegedly deployed by the Telangana government’s Revenue department, arrived with digging bars and hammers, tearing down homes to make way for the Musi Riverfront Development Project. “The previous night, Revenue officials selected 10 houses each from Shankar Nagar and Moosa Nagar, and forcibly shifted the residents to the double-bedroom housing colony in Pilli Gudiselu, Chanchalguda. When I opposed, Malakpet legislator Ahmed bin Abdullah Balala called and tried to persuade me, saying the alternative housing was nearby. He asked me not to interfere,” shares Syed Bilal, a local social activist.

Balala could not be contacted to verify the claim.

The next day, all hell broke loose. Three tehsildars were specifically deployed to oversee the relocation. Residents were reportedly told they would forfeit their right to alternative housing if they did not move immediately.

“The house where my four children resided with their families, was in the name of my daughter, who is disabled. She alone was given a double bedroom unit in Pratapsingaram in compensation, while my sons had to run in search of rented accommodation costing ₹10,000 and above,” says Mujahid.

Among the very few societies the city still has, Suchitra Film Society in Banashankari stands out as the city’s pioneer. Founded in 1971, it has a legacy spanning over 50 years. During a time when access to international and independent cinema was limited, Suchitra introduced people of Bengaluru to world cinema, rare classics, and art films, building a community of passionate film lovers. This society helped shape the city’s film culture, providing a space where cinema could be discussed, celebrated, and appreciated beyond mainstream trends. Today, however, Suchitra and other film societies like it are struggling to survive in a world transformed by digital entertainment.