Lend an ear to the tales of iconic Indian trees Premium

The Hindu

The Karnataka government even permitted the cremation of Raman on the lawns of the Raman Research Institute (RRI), where he had lived and worked for many years, adds Natesh, an honorary fellow at the Ashoka Trust For Research in Ecology (ATREE), Bengaluru, and a former senior adviser at the Department of Biotechnology in New Delhi. The author goes on to share the picture of a gorgeous primavera tree, Roseodendron donnell-smithii, topped with bold yellow blooms, which was planted to mark the spot where the Nobel laureate was cremated and says, “There could be no better respect given to his memory than to plant such a beautiful tree.”

Sir C.V. Raman was known to be a great lover of trees, plants and flowers, says S. Natesh, the author of the recently launched Iconic Trees of India. Raman’s garden was a source of pride and joy for him, so much so that when he lay on his death bed, he was disappointed that the garden was not visible from his cot, Natesh explains at a recent talk held at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), part of Paraspar, an initiative of IISc’s Office of Communications. So, his caregivers raised his cot so that he could gaze at the garden he loved till he passed away in November 1970, aged 82.

The Karnataka government even permitted the cremation of Raman on the lawns of the Raman Research Institute (RRI), where he had lived and worked for many years, adds Natesh, an honorary fellow at the Ashoka Trust For Research in Ecology (ATREE), Bengaluru, and a former senior adviser at the Department of Biotechnology in New Delhi. The author goes on to share the picture of a gorgeous primavera tree, Roseodendron donnell-smithii, topped with bold yellow blooms, which was planted to mark the spot where the Nobel laureate was cremated and says, “There could be no better respect given to his memory than to plant such a beautiful tree.”

Even though this stunning tree, often referred to as the Raman Tree, no longer stands on the lawns of the RRI campus — it collapsed in 2022 after a lightening strike and has been recently replaced with a Sita Ashoka tree — it is one of the 75 mentioned in Iconic Trees of India.

At the talk, Natesh shows more photographs and stories of some of India’s more such exceptional trees. The criteria he used to decide which of the countless trees to include in his book are age, dimension, historical importance, botanical uniqueness and religious/cultural significance; even unique arrangements (e.g., groves, avenues or even plantations of trees) find a place in the book.

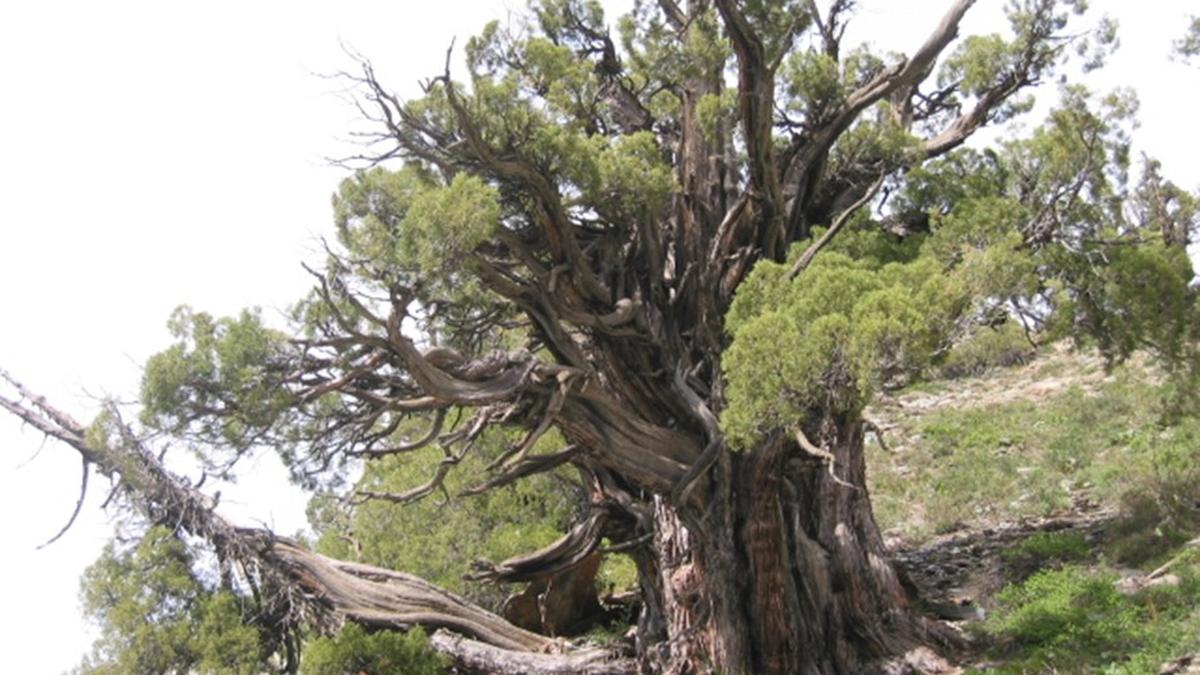

These include the oldest tree in the country, a Himalayan pencil cedar, which is over 2000 years old; the largest tree in the country and indeed the world, the ‘Thimmamma Marrimanu’ banyan tree whose net canopy covers close to 19,107 sqm of land; the Putranjiva tree under which the Raj Tilak ceremony of Maharaja Gulab Singh, founder of the Dogra dynasty, took place in 1822; a historic peepal tree near Dehradun’s clock tower that narrowly escaped being felled thanks to a citizens’ movement; and a giant sequoia in the Tangmarg area of Jammu and Kashmir, often called the loneliest tree in India.

“You can’t help feeling sorry for that tree,” says Natesh, alluding to the “loneliest” tree in the list, native to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California and the largest tree species in the world by wood volume. “Located so far away from its natural home, in an alien habitat in the middle of nowhere, forgotten by those who were responsible for its journey here, devoid of kin, practically unknown to the outside world – underappreciated and unable to reproduce,” elaborates Natesh, who says that through these examples, a few of the 75 documented, he is trying to offer a small glimpse of the rich botanical heritage of India. “There are hundreds more waiting to be discovered,” he says.

Natesh, who grew up in Mysuru and has just moved back to the City of Palaces, says that he has been interested in plants since his childhood. “I grew up in a family where leaves, flowers and fruits were very important for daily worship,” he explains in a post-event interview. “My parents taught me how to identify such plants, which of them were dear to which gods, as well as the medicinal importance of their parts, etc.”