Language harmony versus language power

The Hindu

I don’t know what difference second and third languages made to our lives. I struggled with Hindi in high school because I ran out of my small repertoire of Mohammed Rafi and Kishore Kumar songs to borrow from. The average city Indian speaks three or four languages and has a nodding acquaintance with a couple more. Most of my fellow-students found second and third languages irrelevant to their future careers. But such things become clear only in later life. It is the choice that is important.

My wife’s maternal grandparents were a Rajput and a Malayali. Her mother married an Andhra, her sister a Punjabi. Their son’s wife is Algerian, our son’s is a Scot. That should make for a babel of voices at the dinner table if the generations ate together. Everyone spoke English, though. There were too those who learnt Sanskrit, French and German. Language is only one of the ways we communicate.

I don’t know what difference second and third languages made to our lives. I struggled with Hindi in high school because I ran out of my small repertoire of Mohammed Rafi and Kishore Kumar songs to borrow from. The average city Indian speaks three or four languages and has a nodding acquaintance with a couple more. Most of my fellow-students found second and third languages irrelevant to their future careers. But such things become clear only in later life. It is the choice that is important.

It makes sense for schools to offer an Indian language besides English. India is the second largest English-speaking country in the world, after all. It also seems appropriate to offer the local language, but that too can be seen as an imposition as professionals find jobs in different regions across the country. The children of a Punjabi on job transfer to Bengaluru are unlikely to find exams in Kannada easy. Perhaps there needs to be an option of ‘Higher English’.

The late U.R. Anantamurthy often said that everyone had a duty to learn the language of the state where they lived. This is true. But such knowledge comes from interaction with locals, not from being badly taught from poorly produced textbooks. Coercion usually provokes rejection.

Then there is the issue of qualified language teachers. It is easy to say you can learn any language, but that implies there is a qualified teacher of Bhojpuri, for instance, in Kerala, or Tamil in Ladakh. Our political style has borrowed from the theme in old Western movies: shoot first, regret later. Rules tend to precede an intelligent assessment of the pros and cons. Demonetisation is a good example.

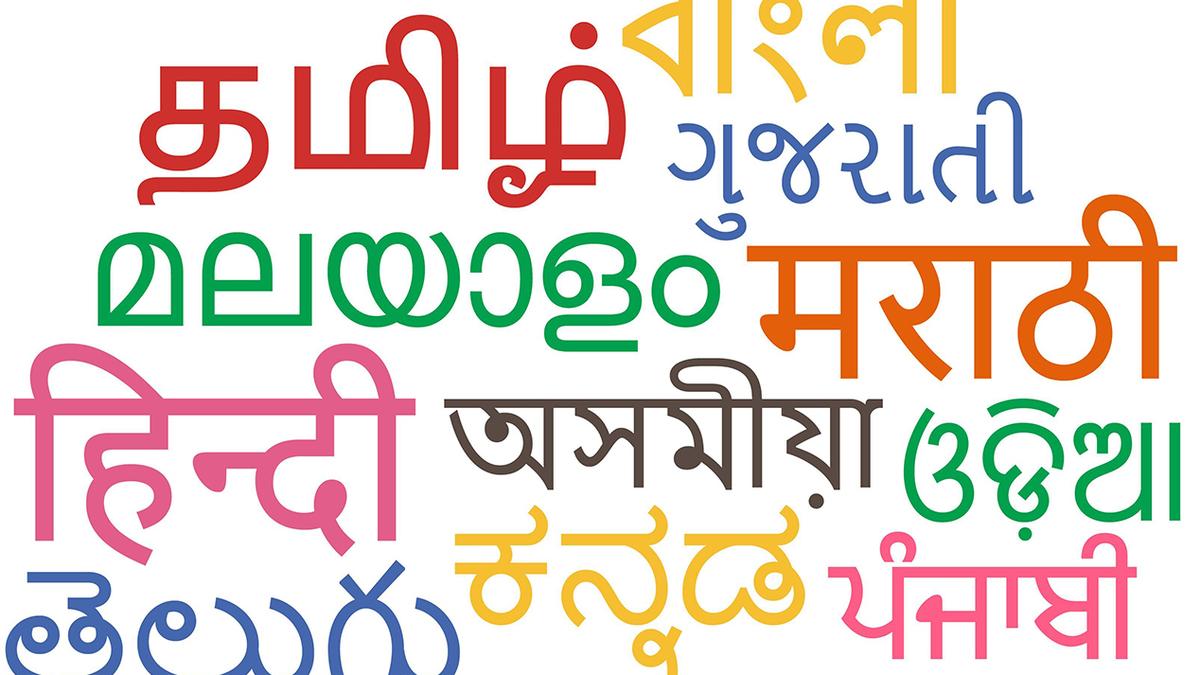

If southern states are wary of Hindi imposition, they have the historical agitations against the move as reference points. In the 1960s, the DMK rode the popular opposition to possible Hindi imposition to come to power in Tamil Nadu. The politics of language is ever nestling beneath the politics of power in our country with its many languages. Forcing people to learn Hindi in the South is as ridiculous as forcing them to learn Tamil in the North.

An unintended consequence of all this has been the language chauvinism in this region. In recent years, Kannada, the language of a gentle people, has seen such nativism. Language warriors have looked into the future and seen the gradual disappearance of their mother tongues and the consequent impact on their culture and tradition. For language is not only about communication. It is a key to history, identity, self-worth and community. Politicians often don’t get this.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game