Inside Mattel, Inc.’s dreamhouse Premium

The Hindu

With ‘Barbie’, Mattel is trying to pull off the ultimate balancing act — juggling profit with pop culture, commodification with aspiration. But can the company’s reinvention survive a culture disenchanted with franchises?

How does Mattel solve a problem of its own design? The problem: a doll, fashioned seven decades ago, with a ridiculously tiny waist, perfectly-arched feet, living in a Pantone 219C pink house, the embodiment of the Perfect Woman™. The California-based toy conglomerate, since the turn of the century, kept drawing cards that augured trouble for its 400+ toy portfolio: misguided acquisitions, dwindling sales, debt crises, stiff competition, a public relations nightmare. More damningly, Barbie dolls, Mattel’s origin story, were proving to be its Achilles Heel. Criticism mounted over its relevance in a world eager to redefine beauty standards and undo gender norms.

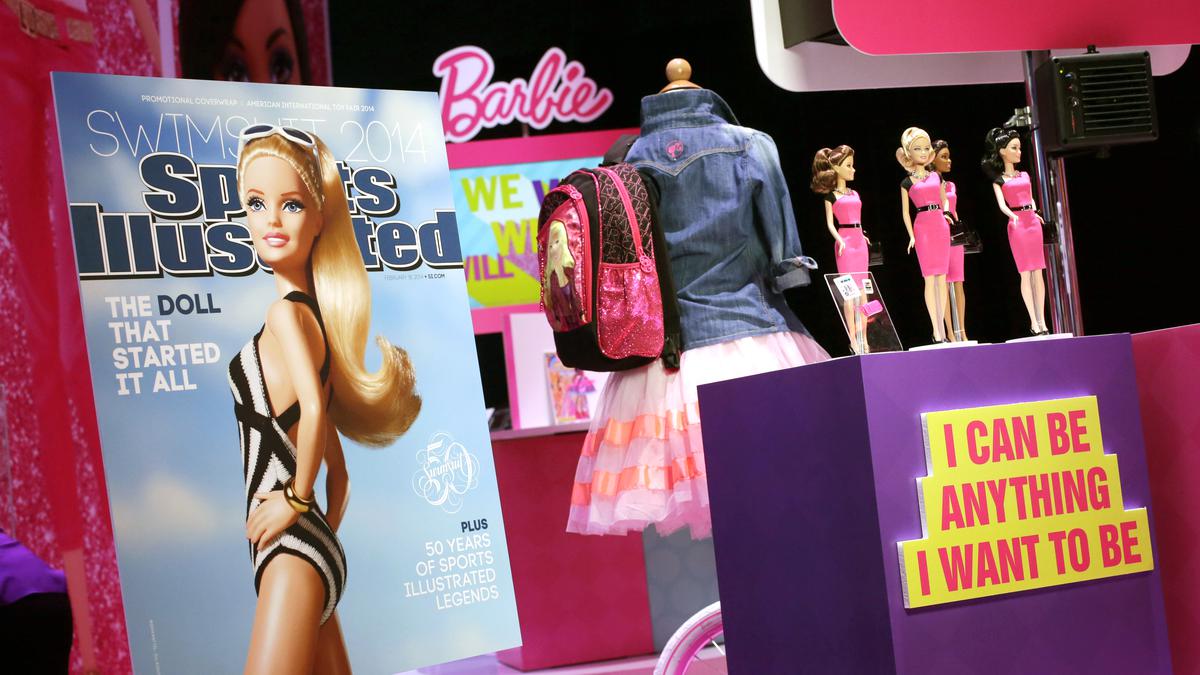

Mattel’s solution? Reinventing the $3 toy into a multi-billion-dollar “pop culture company”, as Richard Dickson, COO and president of Mattel, said in a recent interview. Mattel was ready to have a “dialogue” with consumers, morphing into a “canvas” for conversations and experiences, he says. The canvas currently is painted hot pink: Barbie x Gap clothing, Barbie x Impala rollerskates, Barbie luggage, a Barbie Xbox, a Malibu Dreamhouse. The canvas can be a brand, franchise, an idea. The rumoured $100 million marketing strategy will be a playbook next applied to Hot Wheels, UNO and other playthings in Mattel’s toybox. Welcome to the Mattel Cinematic Universe. Here, life is Mattel’s creation.

Mattel started with a trio in a garage, circa 1945, Los Angeles. Ruth Handler, her husband Elliot and Matt Manson (Mattell is a portmanteau of the latter two; Ruth’s name couldn’t fit into the title, Eliot revealed later). Mattel sold picture frames, then doll furniture and toys. Matt withdrew his participation due to poor health, transferring the remaining stakes to Ruth. Ruth proposed a heretical product (by toy industry standards): a doll with breasts. Her own daughter Barbara played dress-up with baby dolls or one-dimensional paper dolls; it dawned on Ruth that young girls were conditioned to dream of becoming mothers or caregivers -- nothing more, nothing less. This inspiration concretised on seeing Bild Lilli, a doll modelled after a cartoon character in a Swiss local newspaper. The first Barbie doll ambled through the breach wearing a black-and-white striped swimsuit, hooped earrings, sunglasses, priced at $3 then.

Ms. Handler wrote in her 1994 biography: “My whole philosophy of Barbie was that through the doll, the little girl could be anything she wanted to be. Barbie always represented the fact that a woman has choices.” A world, with countless versions, was brought to life: soon came the Ken doll, the Barbie Dreamhouse, Barbie’s best friend Midge, sister Skipper, Ken’s best friend, Barbies of varying skin colours, partaking in sundry professions.

Mattel had acquired 10 other companies by the 1970s, but the Handlers soon resigned when a 1974 investigation found them guilty of falsifying financial statements and mail fraud. Ms. Handler’s next project involved creating prosthetic breasts for cancer survivors (she herself had two mastectomies). This history is documented in the movie, when Ruth’s character in a dream-like setting muses about her illness and financial hiccups. “Ideas live forever, humans not so much,” she says.

Undeterred, Mattle persisted on its way to success. It’s the world’s largest toy maker today in terms of revenue; Barbie and Hot Wheels continue to be its most valued brands. Ms. Handler wrote: “People in the retail business use an expression for a popular product – they say it ‘walks’ off the counter. Barbie didn’t walk. She ran.” Barbie accounted for more than half of Mattel’s sales within initial years of launch..

The old guard gone, Mattel, then helmed by Arthur S. Spear, initiated a strategy of hit and try: acquiring game consoles (almost pushed the company to file for bankruptcy), publishing house (sold four years later), launching action figures (later dropped, causing a $115 million loss), charting paths into multimedia with a $3.6 billion investment in Learning Company (an expert likened to “falling off a cliff’). The company was in financial trouble, recovering briefly in the early 2000s, by refocusing on what they are good at: basic toys. “The strength of Barbie and other important brands — combined with two years of cost-cutting -- have lifted the stock of the company, the nation’s largest toymaker,” a 2003 article in The New York Times noted.

Can RBI’s proposal to waive foreclosure charges help micro and small industries? | Explained Premium

RBI proposes to waive foreclosure charges and prepayment penalties on loans for MSEs, aiming for easy financing.