In Kolkata cemetery, heritage enthusiast brings names of dead alive

The Hindu

Mudar Patherya restores historic tombstones at South Park Street Cemetery, uncovering stories of prominent figures in Kolkata's past.

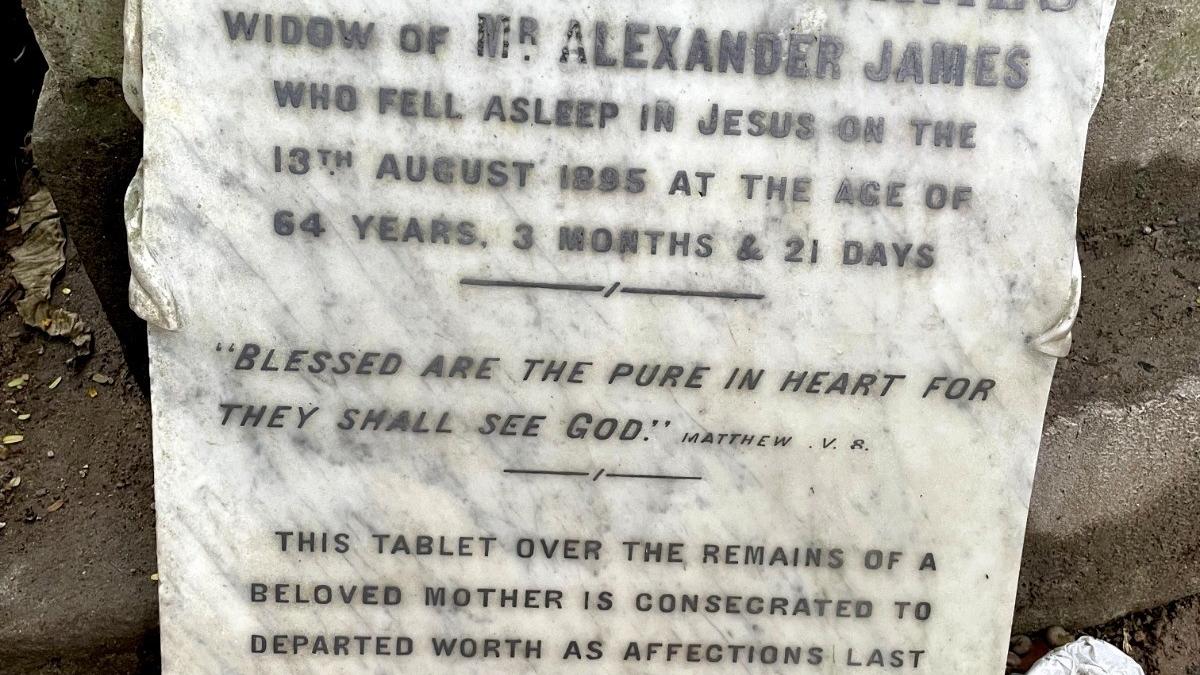

Mudar Patherya is bringing the dead back to life in one of India’s oldest colonial-era burial grounds. This well-known heritage activist of Kolkata is single-handedly getting tombstones, undecipherable over time, cleaned at the South Park Street Cemetery in order to restore a part of the city’s past.

The cemetery, now run by the Christian Burial Board, opened in 1767 and, after being closed briefly in 1790, remained in use until the 1850s. Here lie buried several people who have a prominent place in Indian history, such as Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, Sir William Jones, Col. Robert Kyd, Lt. Col. Colin Mackenzie, and Maj. Gen. Charles Stuart.

“This is possibly the richest repository of funerary architecture outside Europe. So far, I have been able to get 392 tombstones cleaned, there are 300 to 400 more that need to be cleaned, for which I need to raise more funds,” Mr. Patherya told The Hindu.

It all began a month ago when someone from a WhatsApp group on Urdu that he is part of told him about a particular tombstone — tombstone no. 1331 — that had an inscription in Urdu. He wondered why the gravestone of a British man should have an inscription in Urdu, and he went to the cemetery to take a look. The grave turned out to be that of British politician Samuel Smith.

“When I saw the tombstone closely, I also saw inscriptions in English and Bengali. I thought I must clean this up. I wrote to the Christian Burial Board for permission; they called me for a meeting and asked me if I could clean up other tombstones too,” Mr. Patherya said.

The Board, according to him, has been “extremely receptive and cooperative”, as a result of which things moved very fast: it was only last month he approached them for permission and he has already cleaned 392 tombstones after having quickly raised ₹4 lakh through donations from well-wishers.

When he set out for the job, he found that there was no documentation and no cleaning done, possibly for decades, and that structures above the graves were in danger. “But what was amazing was the sense of beauty — the beauty of the structures, the beauty of calligraphy and the sense of emotion. You have the graves of two-year-olds there. If you aggregate the stories written on the tombstones, you get a slice of life lived from 1767 to the 1850s, when the cemetery started filling up,” Mr. Patherya said.