How Shakespeare entered Rajaji’s mind and stayed

The Hindu

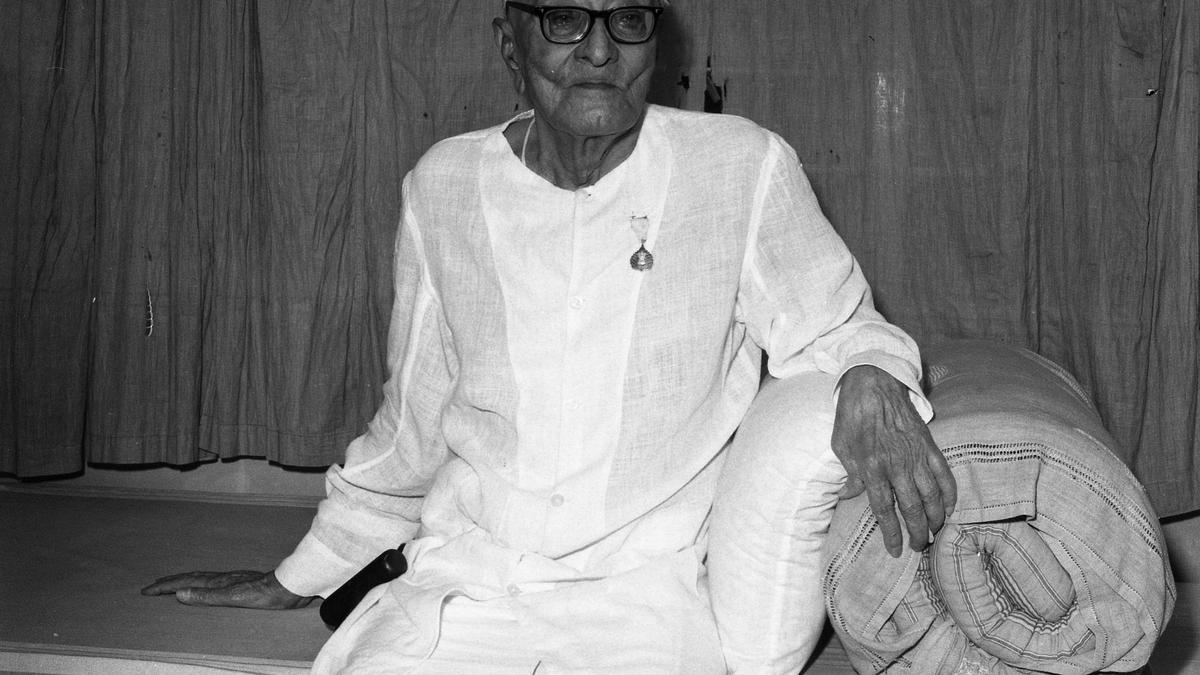

The little candlelight of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets kept Rajaji company throughout

When Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan demitted office as India’s head of state in 1967, he returned to his own home, books and Carnatic music in the city he regarded as his own – Madras. Among the numerous people welcoming him back in their midst was Chakravarti Rajagopalachari. One might have expected Rajaji to say something in praise of Radhakrishnan through apt quotations from the Ramayana or the Mahabharata or the Tirukkural. But no, he said praise of the man was unnecessary. And the unpredictable in him chose to say so, in his ‘Dear Reader’ column in the journal Swarajya, through William Shakespeare’s King John, Act 4, Scene 2: To gild refined gold, to paint the lily/ To throw a perfume on the violet/ To smooth the ice, or add another hue/ Unto the rainbow, or with taper-light/ To seek the beauteous eye of heaven to garnish/ Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.

He asked for that issue of Swarajya to be taken to the Radhakrishnan home and read out to the great man. But he asked the bearer to first rehearse the passage. “To gild refined gold…” went the trainee, pronouncing ‘refined’ as it is normally pronounced. “Not so…,” Rajaji corrected him. “In poetic declamation pronunciation changes… Say ‘refi ned’ not as in find but as in fed…say ‘refined.’” Perfected thus, the poetic message was relayed to its addressee.

Shakespeare and Rajaji went back a long way. We may assume that Rajagopalachari as a student had been introduced to the all-time great poet and playwright by John Guthrie Tait, the Scots professor in Bangalore’s Central College, where the young man studied for his matriculation and from where, in 1896, he wrote his B.A. examination. Shakespeare entered his mind scape early to stay there for ever.

We find Rajagopalachari, the lawyer-turned-nationalist, addressing Gandhi in letters by 1920 as “My dearest Master”, not a form of address to be expected from a 42-year-old for a 51-year-old. In a letter that he wrote to Gandhi in June 1920, upbraiding his ‘Master’ for what the follower thought was a grievous error, he wrote “…My dearest Master – allow me to be harsh, I speak with tears in my eyes – you have no right to act thus…” Upon the ‘Master’ heeding his stinging criticism and advice, the follower sent him a wire: “Words fail me altogether. I hope you have pardoned me.” Somewhere in his sub-conscious he may have gleamed the words of the Steward in All’s Well That Ends Well, Act 3, Scene 4: Write, write, that from the bloody course of war/ My dearest master, your dear son, may hie:/ Bless him at home in peace, whilst I from far/ His name with zealous fervour sanctify: His taken labours bid him me forgive…

In 1921, with the movement for ‘non-co-operation’ in full swing, Rajaji was jailed, along with the whole of the Congress’ leadership and innumerable volunteers. As the key turned to close his cell at Vellore, on December 21, 1921, the sun was setting. Rajaji had with him, apart from a few clothes, a few books – the Bible, the Kural, a work on Socrates, the Mahabharata, Robinson Crusoe and a volume of Shakespeare. Also, pitch darkness. Some three days later, a fresh arrival, Mahomed Ghouse, brought a candle and, on Rajaji’s fourth night in the cell, gave it to him. “Never did I see a candle give such quiet holy light before,” Rajaji wrote in a diary he started to write there, in that first imprisonment of his. It was Christmas eve. It is tempting to imagine that a line from The Merchant of Venice glowed in that light cast by a Muslim fellow-prisoner’s gift of a candle on Yuletide to his Sri Vaishnavite jail-mate: “How far that little candle throws his beams! So shines a good deed in a weary world.” The weary world was with him through the decades that followed, in and out of prison, in and out of public office, in and rarely out of domestic sorrows. The little candlelight of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets kept him company throughout.

Rajaji’s brief tenure as Governor General gave him much to grapple with, but also much to cherish. It brought him the welcome company of a great library in Government House, though without the time needed to read its fabulous holdings. The chance of that privileged position did him another small but, as it turns out, not so small and good turn. It placed in his hands a leather-bound notebook bearing the new tenant’s monogram ‘CR’. This notebook, coming with finger tabs containing the English alphabet, encouraged him to add a dimension to ‘his’ Shakespeare. Pasting a rectangular piece of paper on the cover that simply said ‘Shakespeare’, he started a practice that was to last many years – a compilation in his hand of excerpts from the Bard of Avon, in alphabetic order. A keyword in the excerpt determining the alphabet section selected, he filled its pages with some hundred and more entries over at least two and a half decades. He gave after each entry the name of the play, and the number of the Act and Scene, and sometimes the identity of the speaker — for example, “Just death, kind umpire of men’s miseries – Mortimer in Henry VI (1), II, 5.”

Rajaji’s Shakespeare notebook entries include ‘less known’ Shakespeare quotations, and some which may strike the lay reader as ‘never read before’. They are a chiaroscuro plate of Rajaji’s brooding intellect. They mirror his mind.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game