How does the U.S. electoral college system work? | Explained Premium

The Hindu

U.S. presidential elections explained: Electoral college, faithless electors, House of Representatives, and Senate roles in choosing the President.

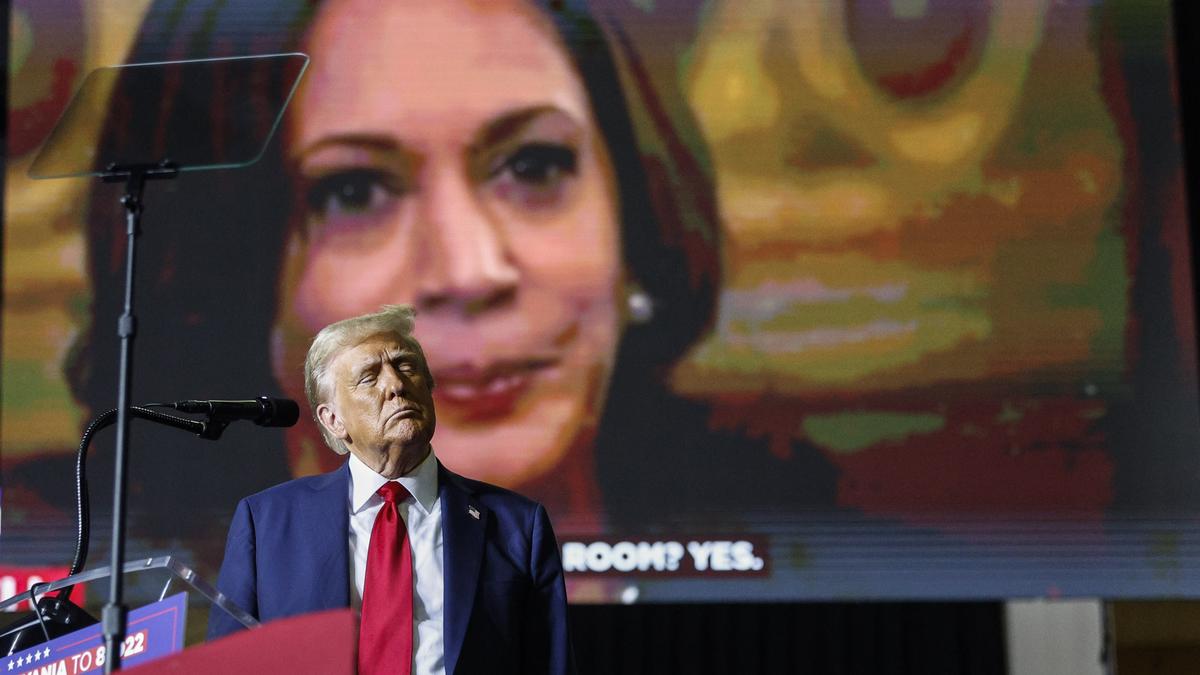

The story so far: U.S. citizens will cast their ballots on November 5, to choose largely between Republican candidate and former President Donald Trump and Vice-President and Democrat Kamala Harris as their 47th President in the 60th quadrennial elections. The U.S. Constitution mandates that instead of securing the popular vote, the winner is the candidate who clinches the maximum number of electoral college votes. Apart from three instances in the 1800s, results in the recent past such as George Bush Jr.’s victory over Al Gore in 2000 and Mr. Trump’s victory over Hilary Clinton (2016) came about in this manner.

The electoral college is an intermediary body or process that chooses the U.S. President. In this system, voters of each State cast their ballots to choose members (or electors) of the electoral college who then vote to select the President.

The number of electors accorded to each State is in proportion to its population and mirrors its number of members in Congress — both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The system, whose origins can be traced back to the days of slavery, was put in place to ensure States got equal representation in the election process.

In the months leading up to the election, different parties nominate their slate of would-be electors in each State. The slate of the party that wins the popular vote in a State goes on to become electors from that State in the electoral college.

Conventionally, these electors meet in December and go by the will of their citizens to vote for the candidate who won the popular vote in their State. If an elector votes against the citizens’ choice, they are called faithless electors, and some States have provisions to prosecute them. In the presidential elections of 2016, there were seven ‘faithless’ electors though their votes made no difference to the result. California, with 54 electoral votes, has the maximum number of seats in the electoral college, followed by Texas with 40 and Florida with 30 while States such as North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, and Vermont have the minimum number of 3. Other than two States (Maine and Nebraska), the winner of the popular vote gets all electoral votes of that State (and the District of Columbia); in other words, “Winner takes all”. There are 538 electoral votes in the college and a candidate must secure at least 270 votes to become President.

According to the U.S. government’s website, the situation has transpired only twice — in 1800 and 1824. On both occasions, the House of Representatives spawned a solution by electing Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams respectively as President.

Given the current composition of States and their voters, such a situation is highly unlikely. However, if a situation were to arise, Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution and the 12th Amendment mandate that the election moves to the House of Representatives where the newly elected 435 members are sworn in and vote on who becomes President.