Explained | Why a room-temperature superconductor paper is turning so many heads Premium

The Hindu

In the face of uncertainty, the scientific curiosity of researchers and the obvious significance of the discovery that has been claimed is likely to prevail.

A portion of the electricity generated at every power plant is lost during transmission because the wires and cables that carry the current have electrical resistance. We can mitigate this to a large extent if we use a material that does not resist the flow of current. Physicists discovered such materials a century ago: they are called superconductors. They have since realised that superconductors can exhibit truly quantum phenomena that have the potential to enable revolutionary technologies, including enabling efficient quantum computers.

All the materials we know to be superconductors become that way in special circumstances; outside those circumstances, they resist the flow of current. For example, aluminium becomes superconducting at a devilishly cold temperature of less than –250° C.

Physicists and engineers have been toiling to find materials that superconduct electricity in ambient conditions, i.e. at one or a few atmospheres of pressure and at room temperature. Given their potential, finding such materials is one of the holy grails of physics and materials science.

The theory that explains why some materials become superconductors in some conditions suggests that hydrogen and materials based on it could hold great promise in this pursuit. And just as predicted, in 2019, scientists in Germany found lanthanum hydride (LaH 10) to be a superconductor at –20° C, but under more than a million atmospheres of pressure – pressure that is only realised at the centre of the earth!

This is where a new study, published in Nature on March 8, enters the plot. Researchers in the U.S., led by Ranga Dias at the University of Rochester, reported discovering room-temperature superconductivity in nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride at roughly a thousand atmospheres of pressure, which is on the face of it a great advance.

The key is the choice of the material; specifically, the authors suggest that the presence of nitrogen is what works the magic. They found a way to push some nitrogen into the crystal of lutetium hydride by developing a high-pressure synthesis process. Superconductivity in the material is brought about by the (microscopic) jiggling motion of the crystal, and the investigators intuited that the right amount of nitrogen could induce the right amount of jiggling: to produce superconductivity at room temperature but without destabilising the crystal.

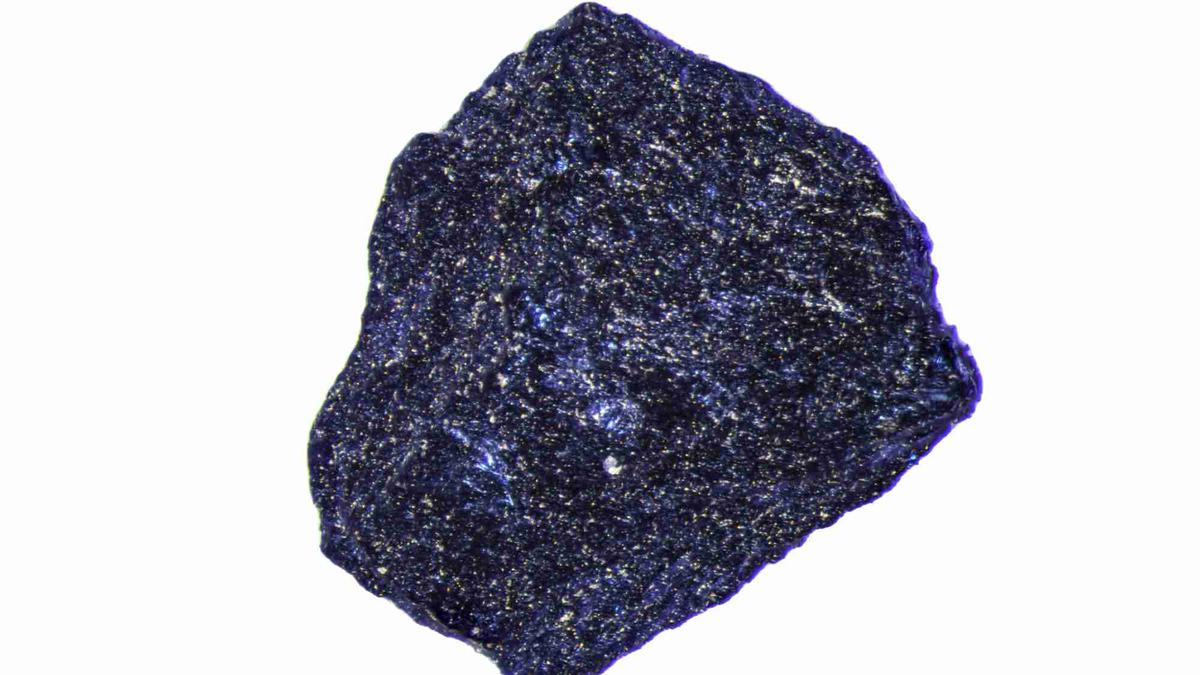

In fact, the nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride that Dias et al. produced is stable in ambient conditions (with a blue colour) but is not yet superconducting.

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game

Run 3 Space | Play Space Running Game Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game

Traffic Jam 3D | Online Racing Game Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game

Duck Hunt | Play Old Classic Game