Explained | What is the debate around star ratings for food packets mooted by FSSAI?

The Hindu

What decision has FSSAI taken? Why is there opposition to the health-star rating system?

The story so far: The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is expected to issue a draft regulation for labels on front of food packets that will inform consumers if a product is high in salt, sugar and fat. It is expected to propose a system under which stars will be assigned to a product, which has earned the ire of public health experts and consumer organisations who say it will be misleading and ineffective. Health experts are demanding that the FSSAI instead recommend the “warning label” system which has proven to have altered consumer behaviour.

In the past three decades, the country’s disease patterns have shifted. While mortality due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases has declined and India’s population is living longer, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and injuries are increasingly contributing to the overall disease burden. In 2016, NCDs accounted for 55% of premature death and disability in the country. Indians also have a disposition for excessive fat around the stomach and abdomen which leads to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. According to the National Family Health Survey-5 (2019-2021), 47.7% of men and 56.7% of women have high risk waist-to-hip ratio. An increased consumption of packaged and junk food has also led to a double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition among children. Over half of the children and adolescents, whether under-nourished or with normal weight, are at risk of cardiovascular diseases, according to an analysis by the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey in India (2016-2018).

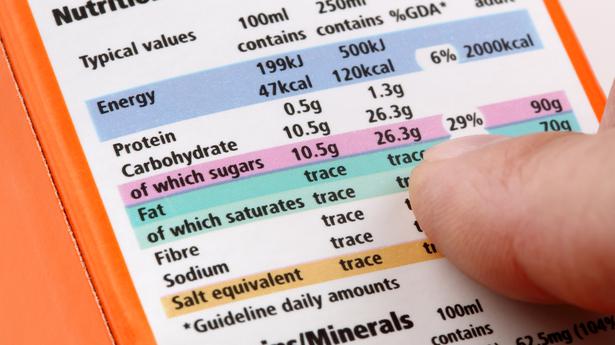

Reducing sugar, salt, and fat is among the best ways to prevent and control non-communicable diseases. While the FSSAI requires mandatory disclosure of nutrition information on food packets, this is located on the back of a packet and is difficult to interpret.

At a stakeholder's meeting on February 15, 2022, three important decisions were taken on what would be the content of the draft regulations on front-of-package labelling. These included threshold levels to be used to determine whether a food product was high in sugar, salt and fat; that the implementation will be voluntary for a period of four years before it is made mandatory; and that the health-star rating system would be used as labels on the basis of a study commissioned by the FSSAI and conducted by IIM-Ahmedabad. The food industry agreed with the FSSAI's decision on the issue of mandatory implementation and use of ratings, and sought more time to study the issue of thresholds. The World Health Organization representative said the thresholds levels were lenient, while the consumer organisations opposed all three decisions.

The biggest contention is over the use of a health-star rating system that uses 1/2 a star to five stars to indicate the overall nutrition profile of a product. Despite objections, FSSAI CEO Arun Singhal told The Hindu that he stands by the IIM-A study as it is based on a survey of 20,500 people. He said stakeholders could share their comments once the draft regulations were made public. The FSSAI's scientific panel will then take that into consideration.

In a health-star rating system, introduced in 2014 in Australia and New Zealand, a product is assigned a certain number of stars using a calculator designed to assess positive (e.g., fruit, nut, protein content, etc) and risk nutrients in food (calories, saturated fat, total sugar, sodium). Scientists have said that such a system misrepresents nutrition science and the presence of fruit in a fruit drink juice does not offset the impact of added sugar. Experts say that so far there is no evidence of the rating system impacting consumer behaviour. The stars can also lead to a ‘health halo’ because of their positive connotation making it harder to identify harmful products. Over 40 global experts have also called the IIM-Ahmedabad study flawed in design and interpretation.

There are many other labelling systems in the world, such as “warning labels” in Chile (which uses black octagonal or stop symbols) and Israel (a red label) for products high in sugar, salt and fat. The ‘Nutri-Score’, used in France, presents a coloured scale of A to E, and the Multiple Traffic Light (MTL), used in the U.K. and other countries depict red (high), amber (medium) or green (low) lights to indicate the risk factors. Global studies have shown a warning label is the only format that has led to a positive impact on food and beverage purchases forcing the industry, for example in Chile, to reformulate their products to remove major amounts of sugar and salt.