Explained | How lasers are helping calcium-41 break into radiometric dating Premium

The Hindu

Advances in laser frequency control and power output have opened the door to using metal isotopes like calcium-41 to be used as tracers in radiometric dating, a field dominated thus far by carbon-14 and its attendant limitations.

Since its invention in 1947, carbon dating has revolutionised many fields of science by allowing scientists to estimate the age of an organic material based on how much carbon-14 it contains. However, carbon-14 has a half-life of 5,700 years, so the technique can’t determine the age of objects older than around 50,000 years.

In 1979, scientists suggested using calcium-41, with a half-life of 99,400 years, instead. It’s produced when cosmic rays from space smash into calcium atoms in the soil, and is found in the earth’s crust, opening the door to dating fossilised bones and rock. But several problems need to be overcome before it can be used to reliably date objects.

One important advancement was reported in Nature Physicsin March 2023.

When an organic entity is alive, its body keeps absorbing and losing carbon-14 atoms. When it dies, this process stops and the extant carbon-14 starts to decay away. Using the difference between the relative abundance of these atoms in the body and the number that should’ve been there, researchers can estimate when the entity died.

A significant early issue with carbon dating was to detect carbon-14 atoms, which occur once in around 10 12 carbon atoms. Calcium-41 is rarer, occurring once in around 10 15 calcium atoms.

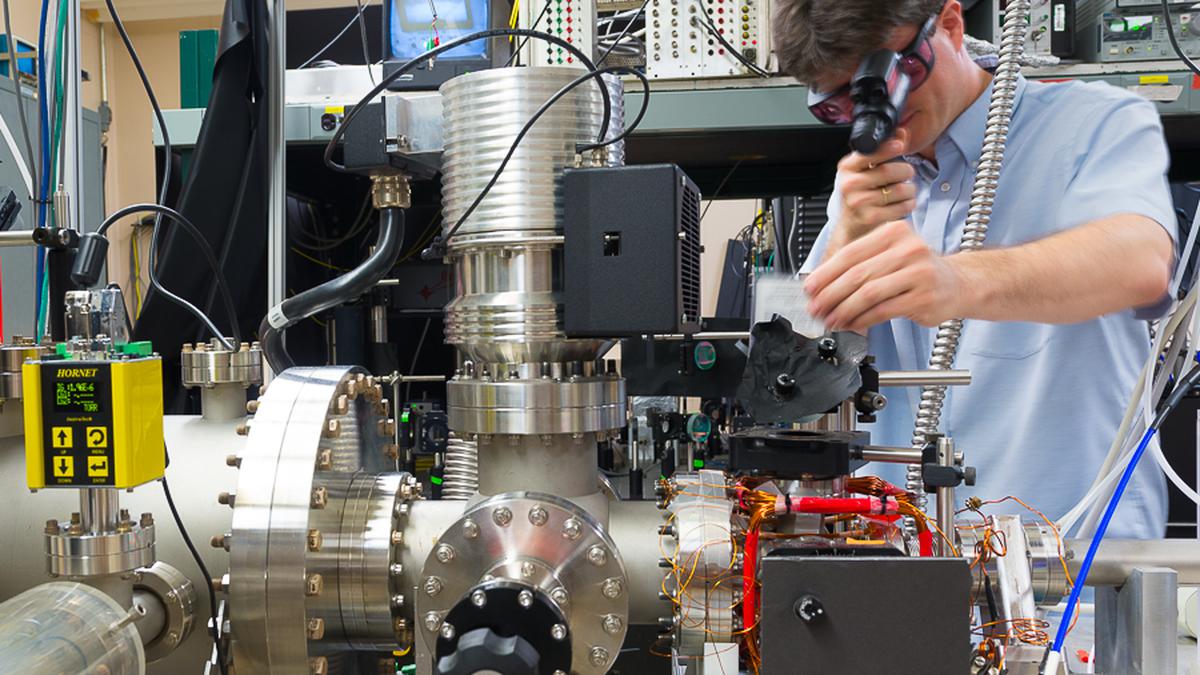

In the new study, researchers at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), Hefei, pitched a technique called atom-trap trace analysis (ATTA) as a solution. ATTA is sensitive enough to spot these atoms; specific enough to not confuse them for other similar atoms; and fits on a tabletop.

A sample is vaporised in an oven. The atoms in the vapour are laser-cooled and loaded into a cage made of light and magnetic fields.