Explained | Does palaeogenomics explain our origins?

The Hindu

Why is this year’s Nobel Prize for Medicine important for the study of human evolution? How did Svante Pääbo pioneer a method to analyse ancient DNA sans contamination? What is the physiological relevance of knowing the ancient flow of genes to present-day humans?

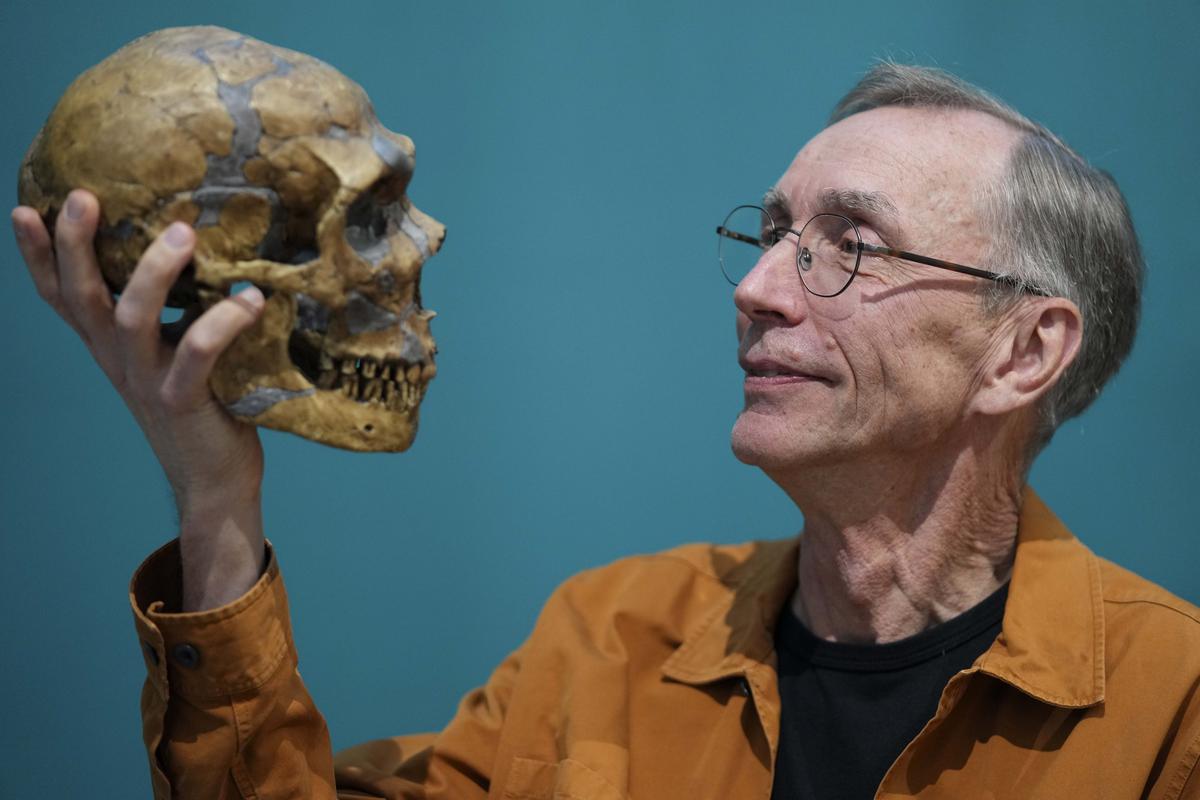

The story so far: The Nobel Prize for Physiology this year has been awarded to Svante Pääbo, Swedish geneticist, who pioneered the field of palaeogenomics, or the study of ancient hominins by extracting their DNA.

Pääbo is the Director of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and has, over three decades, uniquely threaded three scientific disciplines: palaeontology, genomics and evolution. The study of ancient humans has historically been limited to analysing their bone and objects around them such as weapons, utensils, tools and dwellings. Pääbo pioneered the use of DNA, the genetic blueprint present in all life, to examine questions about the relatedness of various ancient human species. He proved that Neanderthals, a cousin of the human species that evolved 1,00,000 years before humans, interbred with people and a fraction of their genes — about 1-4% — live on in those of European and Asian ancestry. Later on, Pääbo’s lab, after analysing a 40,000-year-old finger bone from a Siberian cave, proved that it belonged to a new species of hominin called Denisova. This was the first time that a new species had been discovered based on DNA analysis and this species too had lived and interbred with humans.

The challenge with extracting DNA from fossils is that it degrades fairly quickly and there is little usable material. Because such bones may have passed through several hands, the chances of it being contaminated by human as well as other bacterial DNA get higher. This has been one of the major stumbling blocks to analysing DNA from fossils. One of Pääbo’s early forays was extracting DNA from a 2,500-year-old Egyptian mummy and while it caused a stir and helped his career, much later in life he said that the mummy-DNA was likely contaminated.

DNA is concentrated in two different compartments within the cell: the nucleus and mitochondria, the latter being the powerhouse of the cell. Nuclear DNA stores most of the genetic information, while the much smaller mitochondrial genome is present in thousands of copies and therefore more retrievable. In 1990, Pääbo, as a newly appointed Professor at the University of Munich, took the call to analyse DNA from Neanderthal mitochondria. With his techniques, Pääbo managed to sequence a region of mitochondrial DNA from a 40,000-year-old piece of bone. This was the first time a genome from an extinct human relative was pieced together. Subsequently, he managed to extract enough nuclear DNA from Neanderthal bones to publish the first Neanderthal genome sequence in 2010. This was significant considering that the first complete human genome was published only in 2003.

Pääbo’s most important contribution is demonstrating that ancient DNA can be reliably extracted, analysed and compared with that of other humans and primates to examine what parts of our DNA make one distinctly human or Neanderthal. Thanks to his work we know that Europeans and Asians carry anywhere between 1%-4% of Neanderthal DNA and there is almost no Neanderthal DNA in those of purely African ancestry. Comparative analyses with the human genome demonstrated that the most recent common ancestor of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived around 8,00,000 years ago. In 2008, a 40,000 year-old fragment from a finger-bone, sourced from a Siberian cave in a region called Denisova, yielded DNA that, analysis from Pääbo’s lab revealed, was from an entirely new species of hominin called Denisova. Further analysis showed that they too had interbred with humans and that 6% of human genomes in parts of South East Asia are of Denisovan ancestry.

Editorial | Exhuming new light

The study of ancient DNA provides an independent way to test theories of evolution and the relatedness of population groups. In 2018, an analysis of DNA extracted from skeletons at Haryana’s Rakhigarhi — reported to be a prominent Indus Valley civilisation site — provoked an old debate about the indigenousness of ancient Indian population. These fossils, about 4,500 years old, have better preserved DNA than those analysed in Pääbo’s labs as they are about 10-times younger. The Rakhigarhi fossils showed that these Harappan denizens lacked ancestry from Central Asians or Iranian Farmers and stoked a debate on whether this proved or disproved ‘Aryan migration.’ Palaeogenomics also gives clues into disease. Researchers have analysed dental fossils to glean insights on dental infections.

We know birds, animals and insects constantly communicate with each other by making certain sounds. But when we think about plants, we do not ever think of them communicating. Charles Darwin, an eminent biologist, thought otherwise. Plants might appear the quiet, silent and solitary type of organisms but they have a complex way of communicating which is interesting and important for their survival.