Pichwai paintings: Yugdeepak Soni’s brush with the divine

The Hindu

Indradhanush, an exhibition of paintings in the Pichwai tradition by Yugdeepak Soni, traverses the realms of fantasy, culture and skill

In the late 16th Century, the borderlands of Mewar was wild country inhabited by warring tribes and weary travellers on the old caravan routes that snaked around the Thar desert. But its heart, a few hundred miles to the South, was peppered with lakes, and the colour-drained landscape where only windblown acacia survived gave way to verdant valleys, forests and ancient wells where bulls drew water.

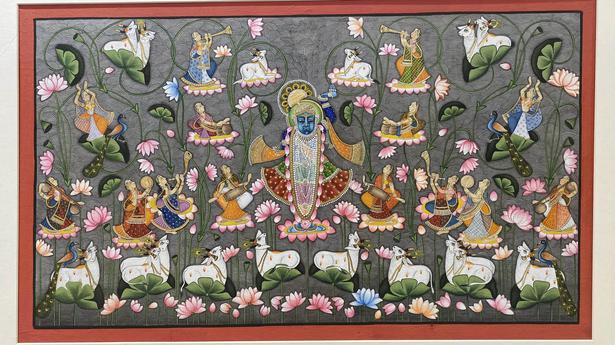

Here, in what is now Rajsamand district, was raised the Shrinathji temple at Nathdwara, pilgrim centre for Vaishnavites and birthplace of the Pichwai tradition of painting. The paintings, predominantly of Krishna with large eyes and a stocky build, earned their name because they were hung behind the deity ( peech-behind, vai-hang). In the four centuries since, Pichwai has come to encompass various themes – the Ras Lila, Jain folklore, the pantheon of Hindu gods, the Hanuman Chalisa, scenes from courtly life, and local flora and fauna – although it is Shrinathji as the cowherd, holding up Mount Govardhan, and appearing to his devotees that still holds forte.

At a workshop as part of Indradhanush, an exhibition of Pichwai paintings, artist Yugdeepak Soni traverses the cultural distance of this art form, as he draws the outline of a woman on a sheet of handmade paper after rubbing it down with onyx. The figure is characteristic of the Mewar school, drawn in profile with almond-shaped eyes and a sharp nose. Soni fills the colours of her skirt and bodice, line by line, using a fine-tipped brush, with the practised ease of a painter who has spent years mastering the form.

“My introduction to Pichwai came after I dropped out of school. I was packed off to Bhilwara for a couple of years, to the house of my maternal uncle who had learnt from my great grandfather, the renowned Badri Lal Chitrakar. I felt at home with the brush, learning from the best on how to make pigments, the technique, how to play with colours, find inspiration and, most importantly, to feel joy while pursuing it. If there is joy inside you, the colours will find you,” says Soni, who now lives in Udaipur. “I’ve been painting for two decades, but I’m still learning. Mistakes happen in the concept and the scale of the work since a single work takes months. Reading folklore, mythology and observing cultural events help anchor the art, though some of the inspiration on how to apply the style comes from previous works.”

Primarily painted on cotton cloth, muslin or handmade paper, over time, Pichwai moved from temples to opulent drawing rooms and from the raag-bhog-shringar (music, food and jewellery for the deity) format to homespun vignettes of rural Rajasthan. The exhibition showcases 55 of Soni’s works, some painted over the course of the pandemic, with an array of brushes and colour. “For the eye and brow, the single-hair squirrel tail brush is used, while the brush made of mongoose hair is used for thicker lines,” says Soni, adding that he uses indigo, metallic and mineral paints, and gold foil, especially while executing the Mughal and Rajput styles.

The paintings are in varied sizes, the cloth panels being larger, and the ones on paper more crowded with elements. Banana trees hold their own in a sea of other trees, peacocks cavort as grey-blue-white monsoon clouds scud across an indigo sky in curls, cows trot through the landscape and also line the well-defined borders as women dance with dream-like intensity.

The hanging display allows the viewer to engage with the painting and gaze at the detail of the artist’s firm hand. Colours that are ripe and rounded fill them, restrained only by geometric precision. Fillers, like chattris, boats, lotuses and orchards are scattered in odd spaces keeping to the theme.