Colonial Bengal explored through ‘pat’ paintings at DAG’s art show in Delhi

The Hindu

DAG exhibition on art from early 20th Century Bengal

One monsoon day in 1757, in the mango orchards of Plassey, a town that stands between Calcutta and Murshidabad, the British established their empire defeating Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula’s forces. And so, to this land stretching from the foothills of the Himalayas to the steaming marshes through which a thousand tributaries flow into the Bay of Bengal, East India Company galleons sailed in and weighed anchor. Legend has it that administrator Job Charnock ‘founded’ the city of Calcutta at the site of three extant villages, near the banyan tree where he liked to smoke his hubble-bubble.

Over time, Calcutta became the hub for Company trade, capital of the sub-continent, seat of the province of Bengal and the second city of empire, after London. Businessmen and soldiers, artists and memsahibs, all drawn to Bengal’s riches in wealth and culture, flocked to it. It led to an extraordinary mingling that resulted in the flourishing of art that drew inspiration from everywhere while remaining true to its local tradition of technique.

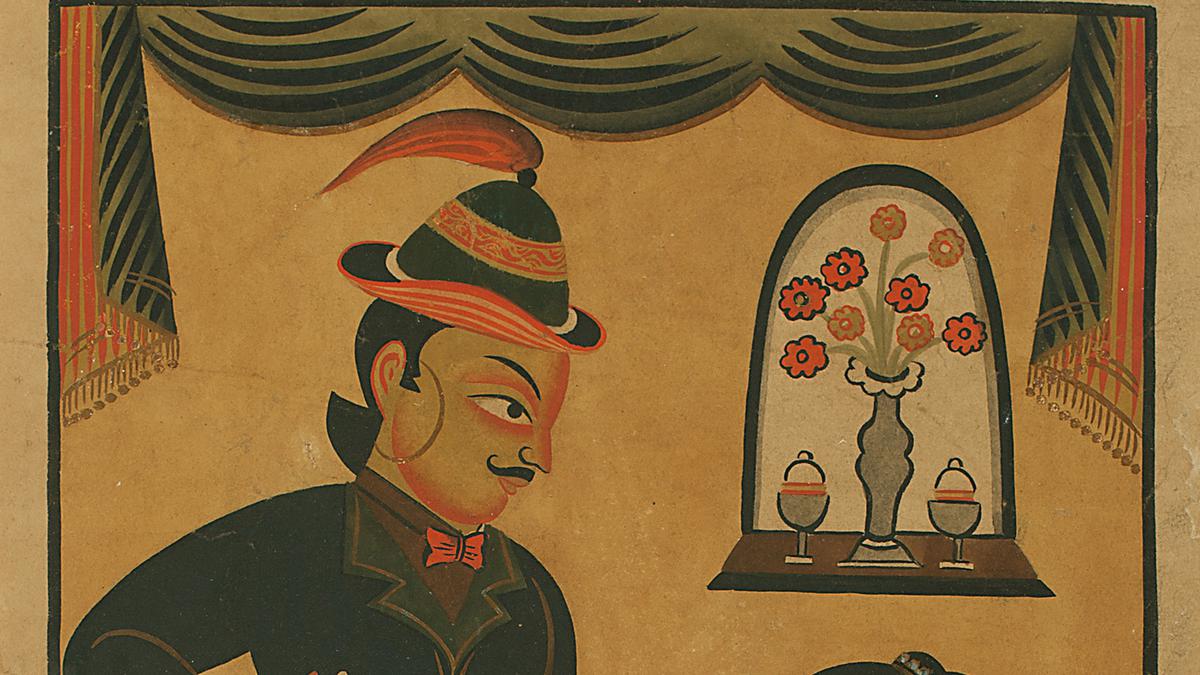

Drawing from its strong repository of art from 19th Century Bengal, Delhi-based DAG (Delhi Art Gallery) has in The Babu & The Bazaar, a display of oil paintings, Kalighat pats — both religious and secular, reverse paintings on glass from Canton (present-day Guangzhou), and early printmaking. The exhibition, with 250 artworks and archival objects, has been in the making for nearly five years and includes works by unidentified artists. Pats are rarely seen on display — the only other prominent collection is at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The exhibition has an accompanying publication by the same name in which Aditi Nath Sarkar and Shatadeep Maitra, who have curated the show, lend their expertise on the genres, the colours used by the artists and why the exhibition is a reflection of the Bengal of yore.

Aditi Nath is an associate professor at the Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of Information and Communication Technology, Gandhinagar, and responsible for creating digitised paper archives on Satyajit Ray’s work. Shatadeep is a member of the exhibitions team at DAG.

In an email interview, Aditi Nath says that the exhibition showcases works that occur after the initial wave of European artists, but before the rise of individually recognised artists like Raja Ravi Varma and Abanindranath Tagore. “The beating heart of the exhibition is the Kalighat pat paintings, a genre of popular watercolour art that proliferated the markets of Calcutta. Wealthy people commissioned special works on canvas on similar themes. Art prints that arrived in Calcutta during the later 19th Century also copied pat designs. Local artists created images primarily of Hindu deities, using western mediums, such as watercolour and oil pigments on paper and canvases. Printing technology like lithography and oleography was later used.”

Aditi Nath adds that there were challenges to dating the work as many of them came from unnamed sources, although certain rubrics were used. “For oils, it was deciphered from the technique utilised by artists. The art school at Calcutta opened in 1854 and taught European naturalism. So, the group of works where western tenets of realism are used, such as perspective, must have come after. Contrastingly, there exist oil works that used traditional tools such as foreshortening and flattened perspectives. The Raj Bhavan with its lion gates was built in 1819, so the Sarpa Satra painting that shows a similar gate must have come after. Non-religious pats are seen in the last quarter of the 19th Century. During this period, the Tarakeshwar scandal occurred — creating certain social stereotypes, like the deracinated babu or the woman as an adulteress. Many paintings also utilise a silver pigment called rang, essentially colloidal tin. When this school was on the decline, this pigment was replaced with white gouache paint. A few Kalighats utilise lithographed outlines, which was a printing technology that was only available en-masse from the 1870s.”